Illustration by Greg Groesch/The Washington Times |

A barrage of statistics makes clear that contemporary Muslims have fallen behind other peoples, whether the topic be health, corruption, longevity, literacy, human rights, personal security, income, or power. But why? Four competing explanations exist, each fraught with implications.

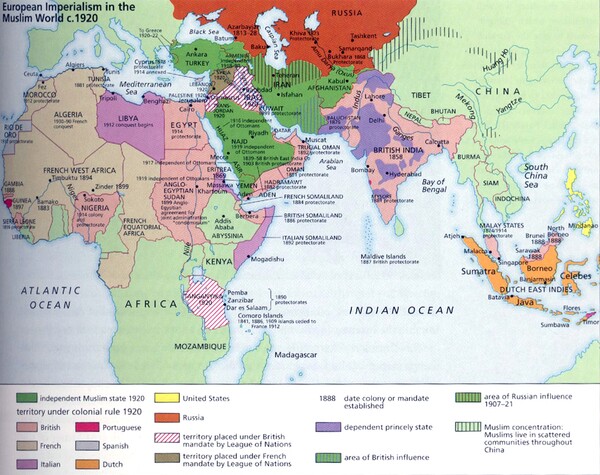

First, the global Left and Islamists blame Western imperialism. For them, today’s tribulations follow inevitably on the two centuries after 1760 when nearly all Muslims fell under the control of 16 majority-Christian states (the United Kingdom, Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Italy, Greece, Russia, Ethiopia, the Philippines, and the United States).

But this accusation ignores two key facts. First, Muslims lagged behind much of the rest of the world in those indices long before 1760 – which helps explain why they came under Western control in the first place. Second, Western control ended about seven decades ago, affording plenty of time to blossom and succeed, as so many non-Muslim peoples have; compare Singapore/Malaysia, India/Pakistan, Israel/Palestinians, or North/South Cyprus.

An outline of Muslims under Christian rule in 1920. |

Second, analysts hostile to Islam tend to blame that religion for Muslim tribulations. Ascribing Muslims’ medieval success to appropriating the contributions of cultures subjugated by force, such as the Roman, Greek, and Iranian, they portray Islam as a stultifying influence that encourages rote learning, inculcates fatalism, and breeds fanaticism. But this too is illogical: if Islam permitted Muslims successfully to borrow from other civilizations a millennium ago, how can it prohibit a similar borrowing today?

Personally, this historian advocates a third explanation: that various factors – rejection of original thought and the Mongolian invasion especially – caused medieval Islamic civilization to decline even as Europe took off. Then, a searing mutual disdain and hostility blocked Muslims from learning from Christians. Had modernity been invented in China, Muslims would be far more advanced today.

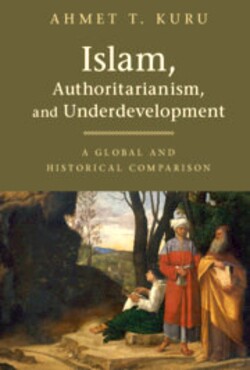

These contending interpretations come to mind on reading Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Comparison (Cambridge University Press, 2019), a book offering an important fourth explanation. Ahmet T. Kuru, a professor of political science at San Diego State University, argues that too-close relations between religious and political authorities stifled Muslim creativity over the past millennium, and that this coalition needs to be broken for Muslims to surge ahead. His thesis bears serious consideration. (The following quotes come from a précis of his book.)

Kuru starts by recalling that “a certain degree of separation between the ulema (the religious leaders who represented Islamic knowledge, education and law) and political rulers” characterized the Muslim Golden Age of the eighth to eleventh centuries c.e., when Muslims enjoyed a wealth and power that put them at the forefront of civilization. In particular, “the overwhelming majority of the ulema and their families were working in non-governmental jobs, particularly in commerce.” The resulting religious and philosophical diversity made early Muslim societies dynamic.

Too-close relations between religious and political authorities stifled Muslim creativity over the past millennium and this coalition needs to be broken for Muslims to surge ahead.

Starting in the mid-eleventh century, “the ulema-state alliance began to emerge in today’s Central Asia, Iran and Iraq.” It then spread to Syria, Egypt, and beyond, causing the marginalization of the intellectual and economic classes. In turn, that lead to a decline in Muslim scientific productivity and economic dynamism.

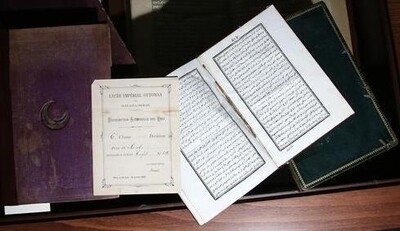

For example, Europeans invented the printing press around 1440 but it took nearly three centuries for Muslims to print a book in Arabic script. This extreme delay followed on the absence of “an intellectual class to appreciate the scholarly significance of the printing press [and] a merchant class to understand the financial opportunities of print-capitalism. The military commanders in Muslim empires did not see the value of the printing press and the ulema regarded it as a threat to their monopoly over education.” As a result, in the eighteenth century, European presses printed 20,000 books to each solitary one printed in the Ottoman Empire. Even today, Arabic books make up just 1.1 percent of global production.

The first printed book in Turkish, Lugat-i Vankulu, was published in 1729. |

Nineteenth-century reforms did not address the ulema-state alliance and so failed. Subsequent efforts fared even worse due to a combination of military-led expansion of state power, proliferating radical ideologies, and insecure secularist leaders. Then, disproportionate hydrocarbon revenues “hindered democratization and created rentier states.”

Looking ahead, Kuru offers Muslims four excellent recommendations: acknowledge the problems of authoritarianism and underdevelopment; blame neither imperialism nor Islam for them; focus on the damage the ulema-state alliance does to intellectuals and entrepreneurs; and develop ideas for “economic restructuring based on productive systems that encourage entrepreneurship.”

Now, will Muslims heed this wise advice? The record, sadly, suggests not.

Daniel Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum.