In a fleeting moment from Lebanese radical Dalal Bizri’s journals of the Lebanese Civil War, in 1975, two young female Lebanese revolutionaries, Zeinab and Dalal herself, pose dutifully for a French journalist from Libération, Jean-Paul Sartre’s radical publication. They stand definitely near sandbag fortifications, AK-47s clenched awkwardly in their hands, expressions hardened by the weight of symbolic expectation. The French journalist, named Karen, meticulously documents these militant women, champions of a feminist revolutionary brigade, fighters ready to lay down their lives for socialist liberation, and contrasts them with the domesticated Western woman.

Yet, as Dalal would later recount with an irony tempered by resignation, their revolutionary fervor was itself a fragile yet skillfully crafted representation. At precisely the moment they first glimpsed their heroic images in print—mythic figures frozen in the gravity of revolutionary struggle against the forces of Maronite reaction and fascism—they were busy peeling and chopping onions for the real actors, the male comrades, quietly confronting the gulf between the imposed image and their lived reality. They laughed then, not without bitterness, recognizing how their lives differ between reality and the revolutionary theater performed for the pleasure of the Western college-educated middle class, far removed from the messy complexities and tragedies of real violence.

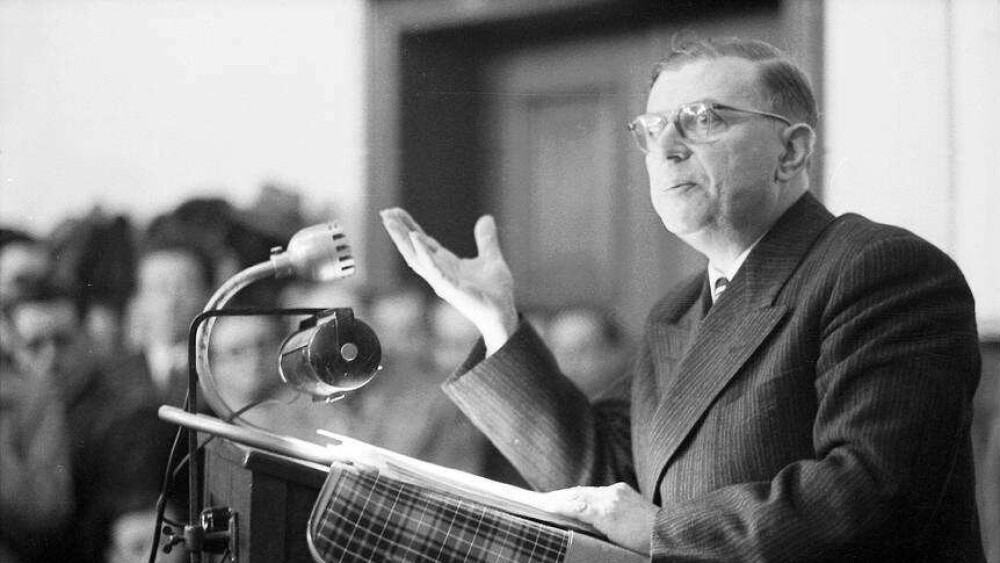

Sartre’s political pornography—his sanctification of the Maoist peasant, the Viet Cong martyr, the Algerian terrorist—was not simply wrongheaded but obscenely self-serving.

This brief story encapsulates a broader, insidious dynamic at play: the deliberate and systematic ideological distortion and myth-making employed by Western intellectuals, journalists, and political activists who craft narratives of revolutionary romanticism, about the heroic female fighter, the noble Palestinian, the lords of resistance, primarily to inflame, inspire, and radicalize, or at best to entertain, their own domestic audiences. It is a carefully choreographed theater of revolution, enacted for distant spectators whose ideological appetites demand heroes and villains reduced to easily digestible images, disconnected entirely from the messy truths of actual lived experiences.

The anecdote from Dalal Bizri’s journal is not merely poignant—it is diagnostic. It distills, in one moment, the fundamental pathology of modern Western intellectual culture: the compulsive construction of revolutionary mythologies for the purpose of domestic radicalization. This is not journalism, nor anthropology, nor solidarity. It is the aestheticized projection of ideological fantasy—an act of symbolic exploitation that uses the “Third World” as a screen upon which to rehearse Western neuroses. And no figure bears more responsibility for this phenomenon than Jean-Paul Sartre.

Raymond Aron, Sartre’s contemporary and nemesis, had already warned against this long before Beirut burned. In The Opium of the Intellectuals, Aron charged Sartre and his fellow Parisian revolutionaries with the worst of intellectual sins: the moral corruption of turning other people’s suffering into ideological theater. Sartre’s political pornography—his sanctification of the Maoist peasant, the Viet Cong martyr, the Algerian terrorist—was not simply wrongheaded but obscenely self-serving. Aron saw what others refused to admit: that these intellectuals, disillusioned by the failure of revolution in Europe, began exporting their ideological yearnings to the poor, the colonized, and the suffering—imagining them not as they were, but as they needed them to be.

Western ideological storytelling, as in Bizri’s encounter, reveals its primary purpose not as truth-telling but as domestic mobilization. Journalists like “Karen” from Libération arrive with a script in hand: they are not here to listen or learn but to consecrate. Their stories do not uncover; they ordain. In this moral pageantry, the Lebanese revolutionary becomes a prop—a brown-skinned Joan of Arc with a Kalashnikov—deployed to stir the revolutionary fervor of the French salon. No one is interested in the onions she chops, the floors she scrubs, or the silence she is expected to maintain while the men talk politics.

Aron’s critique was not merely about accuracy; it was about responsibility. It was a call to intellectual conscience. He saw that Sartre’s revolution was not for the colonized but for the Parisians who wished to re-enchant their sterile world with foreign suffering. In that way, the revolution became a fetish, and the suffering of others its liturgy. The peasant, the militant, the martyr—all were pressed into ideological service to absolve the West of its bourgeois boredom and provide its radicals with the thrill of meaning.

The Western intellectual class, spiritually unmoored and morally adrift, has learned to treat the Third World as a reservoir of usable symbolism.

This is not a distortion of facts—it is the manufacture of idols. The Western intellectual class, spiritually unmoored and morally adrift, has learned to treat the Third World as a reservoir of usable symbolism. They are not interested in complexity or contradiction, because complexity cannot be mythologized. Their gaze is totalitarian: it reduces, simplifies, purifies, and elevates. And in the process, it destroys. For those who live in these myths—those who find themselves portrayed as heroes, savages, or saints—the price is always the same: misrecognition, dehumanization, and finally, silence.

Aron knew that to romanticize is to colonize by other means. The myth of the revolutionary, like all myths, demands sacrifice. And what is sacrificed is truth. Truth is always too ambiguous, too disappointing, too unbeautiful. So they replace it with spectacle. Beirut becomes a stage. The Palestinian becomes a Christ. The Lebanese woman becomes Antigone. And the Western reader is delivered, once again, into the ecstatic certainty of their own moral awakening.

This is imperialism redux: not the conquest of lands, but the conquest of images. It is not soldiers but storytellers who now lead the charge. And their weapons are not guns, but metaphors. Against this, Aron’s rebuke still resounds with prophetic force: stop manufacturing myths. Stop feeding your ideological appetite with the lives of others. Stop turning the tragedies of the world into fuel for your own decadent dreams of revolution, psychosexual or otherwise. In short: grow up, and tell the truth.

The Indigenous Manufacture of Myth: The Lebanese Left and the Fetish of Palestine

But to blame the West alone would be an act of self-exoneration. The same spirit of ideological myth-making, the same hunger for spectacle, sanctity, and simplicity, infected the Third World and Arab Left with equal, if not greater, intensity. Not just, as Bizri recounted, they cooperated willfully in the co-construction of their mythic representation for the Western audience, but they also constructed mythic representations to sustain their own destructive delusions. If the Western intellectual required the image of the revolutionary Third World hero to redeem his bourgeois malaise, the Lebanese radical needed the Palestinian militant to redeem his fractured political identity. In both cases, the result was the same: a fantasy so seductive that entire societies were willing to burn in its name.

If the Western intellectual required the image of the revolutionary Third World hero to redeem his bourgeois malaise, the Lebanese radical

needed the Palestinian militant to redeem his fractured political identity.

By the late 1960s, as Jordan descended into chaos and Palestinian armed struggle matured into a semi-theological dogma, Lebanon’s Left, disillusioned, rudderless, and ideologically fragmented after the collapse of pan-Arabism, found its new spiritual axis in the figure of the Palestinian fighter. The Marxist weekly Socialist Lebanon promised that the entrance of the Palestinian resistance into Lebanon would “revolutionize the Lebanese situation.” This was not strategy. It was not analysis. It was millenarian desire: an apocalyptic hope that the presence of Palestinian arms would alchemize Lebanon’s contradictions into a dialectical utopia.

Dalal Bizri, in her memoir Happy Revolutionary Years, is candid about the delusion. She and her comrades, freshly minted Marxists barely out of adolescence, were electrified not by a mature political program but by proximity to violence and by stories imported from the Paris of 1968, where the student slogan “It’s forbidden to forbid” echoed like prophecy. The Palestinian struggle became their rite of passage, their baptism into the revolutionary sublime. That there was a conflict over actual land, with real people and real tragedies, was beside the point. What mattered was that Palestine had become the condensed signifier of all that needed to be overcome: capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism, sectarianism, boredom. (Reminds you of something?)

To be a Lebanese Leftist, then, was to be organically tied to a Palestinian faction. Solidarity was no longer ethical; it was structural. Whoever did not support the Palestinians had no political future in Lebanon. The cause became a litmus test, a coercive tool, and above all, a semiotic monopoly. All reality, all injustice, all protest, was ultimately about Palestine. A grocer’s prices? Palestine. A teacher’s strike? Palestine. A student’s rebellion? Palestine. The result was the explosion of the first episode of social collapse in the modern Middle East.

Veteran Lebanese Communist Fawwaz Traboulsi would later reflect with brutal clarity: “We wanted to reform by way of the gun… using the Palestinian stick to force the bourgeois to reform.” It was not just a matter of solidarity; it was strategy by proxy, revolution outsourced to a neighboring trauma. The gun, the refugee, the cause—these were not only symbols of struggle, but instruments of coercion, a way for Lebanese radicals to wield borrowed militancy against their own domestic enemies. (This remains to be the strategy of the Iranian regime, the bastard of the Marxist-Islamist copulation.)

Within two or three sessions, these underfed and over-militarized boys were instructed on how to interpret their hunger and displacement through the dialectical materialism of god-hating German philosophers long dead.

And this dogma required its rituals. Affluent students were sent to refugee camps to teach barely literate Palestinian youth the sacred texts of Marxism; “the Theory,” “the Line,” “the Program.” Within two or three sessions, these underfed and over-militarized boys were instructed on how to interpret their hunger and displacement through the dialectical materialism of god-hating German philosophers long dead. Once sufficiently anointed, they were armed and dispatched, sanctified by the blessing of those who saw in their misery not a wound to be healed but a symbol to be exalted.

For the Lebanese Left, the Palestinian was the noble savage; tragic, pure, and brimming with latent revolutionary grace. The entire structure was aesthetic, theological, and performative. Children from Sidon or Tyre, enraptured by Che and Ho Chi Minh, discovered their existential purpose by humiliating elderly shopkeepers under the guise of price control. In a grotesque parody of class struggle, the revolutionary imagination became indistinguishable from juvenile sadism.

This fantasy was not merely ideological; it was aesthetic. The very texture of Palestinian poverty became an object of eroticized admiration. Bizri writes, almost wistfully, of how these boys from the camps possessed a kind of primal masculinity; their bodies gaunt yet strong, their eyes hollow yet defiant. Their speech, rough and unrefined, was praised for its ‘real personality,’ a term that says more about the listener than the speaker. Their Arabic, devoid of cosmopolitan polish, was perceived as pure, rooted, untainted by bourgeois artifice. In other words, it was authentic—and therefore valuable. This aesthetic fetishization was not incidental; it was essential. Without it, the myth could not function. The revolution required not just martyrs but icons. The Palestinian was useful not only because he was poor or angry or armed, but because he looked the part.

Read the full article at Substack.

Published originally on May 25, 2025.