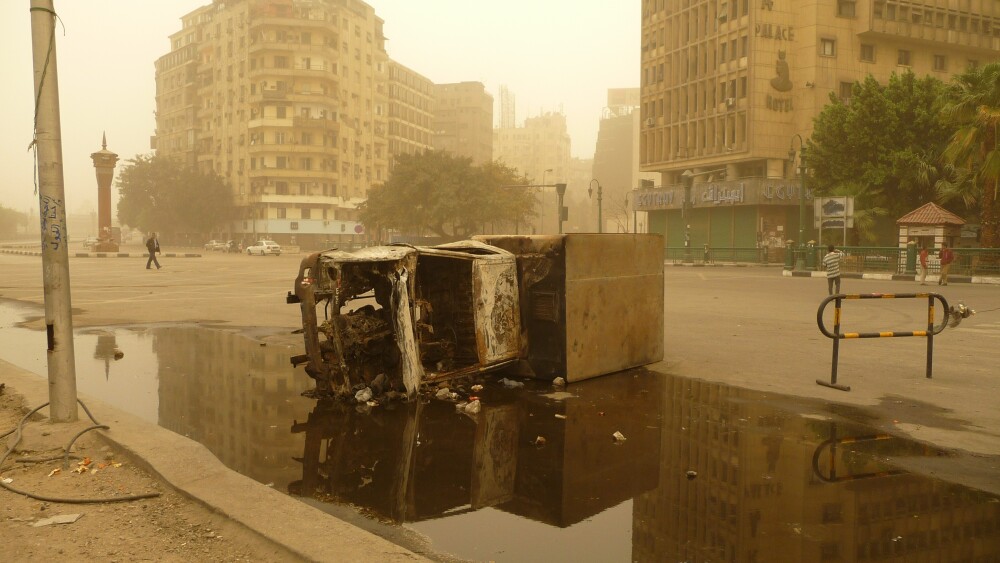

History is a vast necropolis of revolutionary hopes. Its soil is heavy with the bones of false dawns and the skeletons of wrecked ships, each generation interring its own dreams beside the unmarked graves of those who dreamed before them. The Arab Spring lies buried there now, a mass grave in which the brightest hopes of an entire generation of Arabs, and of their Western admirers, rest alongside the uncounted dead. For what began as a cry for liberty became a cascade of state collapse, civil wars, terrorism, and waves of refugees that destabilized not only the Middle East but Europe and the order of the world itself.

Yet even this would be tragedy enough. What haunts us now is something worse: the disappointing discovery that memory grants no mercy, that even the dreams we mourned were concealing nightmares. The brave liberal activists whom the West celebrated—the men and women whom Obama wanted to inherit the governance of the Arab world—have revealed themselves, in the clarity of subsequent years and mature age, to harbor racist and antisemitic convictions so virulent that many an Arab autocrat begins to look, by comparison, worthy of a peace prize.

What began as a cry for liberty became a cascade of state collapse, civil wars, terrorism, and waves of refugees that destabilized not only the Middle East but Europe and the order of the world itself.

The case of Alaa Abd El-Fattah is but the latest episode in this inexhaustible pageant of disillusionment—a revelation that arrives late but loses none of its capacity to shock. Here was the Western-educated Egyptian freedom fighter, the software engineer who spent the better part of twelve years behind bars for the cause of democracy, now discovered to have been, in the very years of his rise to liberal sainthood, an enthusiast of killing “Zionists including civilians,” a soul who found such slaughter “heroic,” who regarded white people as “a blight on the earth,” and who dismissed the British—whose citizenship he now claims—as “dogs and monkeys.”

That the revelation came so late doesn’t reduce its significance. Abd El-Fattah was, along with many others like Bassem Youssef, not a marginal figure but one of the more well-known icons of the Arab Spring’s brightest aspirations. He is Western-educated, half-British through his London-born mother, a software engineer by training, and one of the defining faces of the activist generation: the first cohort of Arabs to be thoroughly Americanized and liberalized, the apparent success story of the neoliberal NGO world-regime. Like Zohran Mamdani, he comes from a family of Third World cultural elites and professionals. His father, Ahmed Seif El-Islam, was a communist activist turned human rights lawyer; his mother, Laila Soueif, a professor of mathematics and tireless scholar-activist; his aunt, Ahdaf Soueif, the most celebrated and most widely translated female novelist from the Arab world. Here was the full pedigree: leftist, feminist, humanist, academic—the children of the Third World intelligentsia wielding Twitter and Facebook in pursuit of the social justice eschaton, the wretched of the beach sands, Fanon’s heirs with frequent flyer miles.

These new Arabs, and the children of upper-middle-class Third World elites at large, were seen as exemplary figures: cosmopolitan, pluralist, post-religious, post-sectarian, hungry for democratic normalcy. Obama said he wanted to see one of them become the President of Egypt. This was the birth of policy and scholarly romance with the myth of “civil society,” the new protagonist of history, replacing the workers and the revolutionaries, tasked with converting national communities into management units in a liberal, rule-based order of technocratic institutions. This myth of the civil society produced a certain kind of Third World protagonist: photogenic, bilingual, media-ready, and tech-savvy, who is supposed to stand for the whole.

They were often seen as cousins to the Atlantic world’s preferred self-portrait: the rising class of NGO professionals, human rights lawyers, peace advocates, conflict-resolution experts, sustainability coaches, post-Christian morality priests, and credentialed stewards of the emerging global order and its final utopia: human rights. It was an image as flattering as it was useful, for it allowed the uprisings to be read as confirmation of a universal script, as vindication of the neoliberal-left world order itself and its civil society’s NGOs. The Arab street, long derided as the most backward and most resistant to democracy, at last wanted what “we” wanted. History, at last, was converging. The Middle East, at last, was entering the moral jurisdiction of liberal expectation. Fukuyama was right. Only two decades too early.

His myth of the civil society produced a certain kind of Third World protagonist: photogenic, bilingual, media-ready, and tech-savvy, who is supposed to stand for the whole.

The story need not be rehearsed again; its outlines are known. The Arab Spring ended not in democratic dawn but in a long winter of civil wars, failed states, refugee crises, and the reassertion of authoritarian rule—where rule survived at all. So complete was the humiliation of Western hopes that we were totally cured of all moral ambition. The very vocabulary of democracy promotion and human rights advocacy has quietly been retired from any serious discourse on the Middle East. Our aspirations have been so chastened that we no longer dream of Arab democracy or human rights; we dream, at most, of tolerable deals with Arab autocrats and a working relationship with the former al-Qaeda fighters who now govern what remains of Syria. The arc of history, it turned out, bends toward nothing in particular.

The fate of the Arab liberal luminaries was no less bleak. Bassem Youssef, the satirist once hailed as Egypt’s Jon Stewart, was forced into exile. Abd El-Fattah languished in Egyptian prisons for over a decade, his youth consumed by concrete and iron. Others, like Mona al-Tahawy, scattered to European capitals and American university towns, their dreams of democratic homelands reduced to op-eds and visiting fellowships and an occasional veteran pride among Western boomers who know a thing or two about Tahrir Square. And yet even this—exile, imprisonment, loss of status—was a gentler fate than that which befell the children of ordinary families, my people, who lacked the privilege of foreign passports, international advocacy campaigns, and the lobbying of Western governments on their behalf. The anonymous dead of Syria and Libya and Yemen, the unnamed disappeared of Sisi’s Egypt, the countless young men and women who could not flee and for whom no hashtag trended—these inherited the truest portion of the Arab Spring’s bequest.

And yet, as if all this were not sufficient cause for grief and disillusionment, the past returns to teach us that we have not yet plumbed the depths of our self-deception. For it is one thing to mourn a dream that failed; it is another to discover that the dream was never what it appeared to be, that beneath the cosmopolitan surface lay something as dark, if not darker, than the autocracies we hoped to replace.

Abd El-Fattah’s return to Britain last week was staged as a final act of triumph, a faint echo of a happy ending to an overall miserable story. The long campaign for his release had succeeded, and the prisoner of conscience was free; Keir Starmer posted his delight for all to see. Within hours, the tableau collapsed as old tweets of Abd El-Fattah resurfaced. In 2010, at the very height of his ascent to liberal iconhood, Abd El-Fattah had declared the killing of “Zionists including civilians” to be “heroic.” He had announced, with what one must assume was pride, that he was “a violent person who advocated the killing of all Zionists.” He had called white people “a blight on the earth” and the British “dogs and monkeys.” He had, according to reports, denied the Holocaust ever took place. These were not the effusions of an uneducated youth radicalized in some Cairo slum; they were the considered opinions of a Western-educated software engineer from one of Egypt’s most distinguished intellectual families at the age of twenty-nine.

For it is one thing to mourn a dream that failed; it is another to discover that the dream was never what it appeared to be, that beneath the cosmopolitan surface lay something as dark, if not darker, than the autocracies we hoped to replace.

The British government, caught between its investment in Abd El-Fattah’s cause and the undeniable substance of his words, issued the only statement available to it: the posts were “abhorrent,” but he remained a British citizen. Abd El-Fattah himself offered an apology, the recognizable apology of our era, in which the offense is attributed to misunderstanding and anger, which is then justified by a litany of Western sins, Iraq, Gaza, and police brutality. And, in a typical liberal toxic move, what is apologized for is not the offensive speech itself, but the way it made people feel. One is left to wonder what Israeli civilians had to do with any of it, or why the appropriate response to Egyptian police violence was to declare white people a blight upon the earth.

But the apology is not the point. The point is what the episode reveals about the nature of the hope that was invested in figures like Abd El-Fattah—and what it reveals about the structure of the worldview he represented. For his sentiments were not idiosyncratic. They were not the private aberration of an otherwise liberal mind. They were, and are, entirely legible within the intellectual formation that produced him: the post-colonial, third-worldist, leftist-humanitarian synthesis that has become the default ideology of the global progressive class. It is the same reason that the new New York City mayor, Zohran Mamdani, seems to have a very hard time finding appointees who hadn’t tweeted antisemitic statements in the past. Within that formation, antisemitism is not an embarrassing residue but a load-bearing wall.

Moreover, Abd El-Fattah is merely another episode in a serial that has long since ceased to surprise. Perhaps the most prominent case is Bassem Youssef, the heart surgeon turned satirist—a man whose career was built with the enthusiastic support of American Jewish producers, who toured synagogues and Hillel houses across the United States, and who was celebrated as the embodiment of liberal Arab wit. After years of devastating loss and failed reinventions in America, Youssef found his second act in the aftermath of October 7th. He relaunched himself to the heights of his former celebrity by becoming the most visible anti-Israel Arab face and defender of Hamas in Western media, appearing on platform after platform to dispute the massacres, to cast doubt on documented atrocities, to explain away what could not be explained. His social media accounts descended into the most vulgar antisemitic obsessions: the Talmud, Jewish control of media and corporations, the old libels dressed in irony for safety. “I’m a comedian!” So explosive was Youssef’s comeback that the Egyptian state, which had once hounded him into exile, reconciled with him and restored a measure of his forfeited glory, and I assume, fortune.

One is left to wonder what Israeli civilians had to do with any of it, or why the appropriate response to Egyptian police violence was to declare white people a blight upon the earth.

Before Youssef, there was Mona Eltahawy—an Egyptian feminist journalist who once very insightfully called Israel “the opium of the Arabs,” a convenient intoxicant by which Arab leaders excused their own failures. She, too, had her drama with the Egyptian police state, her arms broken by security forces in Tahrir Square, before she settled in the United States and built a career as a fearless critic of Arab patriarchy. Gradually, imperceptibly, her passion for the freedom of Egyptian women became a passion for fighting Zionism.

Or let’s remember the sad case of Samira Ibrahim—one of the most celebrated female activists of the Arab Spring’s high noon. In those interim months between Mubarak and Morsi, Ibrahim remained in Tahrir Square, pressing the military for democracy. Her punishment, like that of many young women who dared to occupy public space, was to be arrested and subjected to an invasive “virginity test”—a form of moral assassination in an Arab honor society designed to silence through sexual shame. But Ibrahim proved heroic. Unashamed, she accused the military publicly and told her story, becoming a global symbol of courage. Time named her one of the hundred most influential people in the world. In 2013, the State Department invited her to Washington to receive its International Women of Courage Award from John Kerry and Michelle Obama. And then—surprise—her not-so-old tweets resurfaced. They were recent tweets, actually. On the day of the Bulgarian bus bombing that killed Israeli tourists and a bus driver, she had written: “Today is a very sweet day with a lot of very sweet news.” She had quoted Hitler on the Jews. She had wished, on the anniversary of September 11th, that “every year come with America burning.” When questioned, Ibrahim refused to apologize, blaming the “Zionist lobby” for her lost prize. She returned to Egypt empty-handed and, by all accounts, more celebrated at home than she had ever been.

I could continue. The archive I have is endless. Many will be surprised by all of this, and I am not. You see, I knew many of them. I, too, was in Tahrir Square.

Published originally on December 30, 2025.