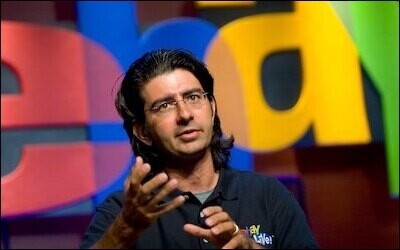

eBay founder Pierre Morad Omidyar’s Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute has promoted biased, politicized scholarship in Middle East studies. |

Pierre Morad Omidyar, who founded the online auction site eBay in 1995, was for years among America’s most enigmatic philanthropists. Maintaining a low profile is difficult for any Silicon Valley billionaire, but Omidyar, of Iranian heritage, managed to fulfill his wish of flying “under the radar” until he resigned from the board of eBay in 2015. Since then, he has played his political hand far more publicly. But not all his undertakings garner headlines.

A case in point is the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute (Roshan, RCHI), one of Omidyar’s philanthropic undertakings. Tax returns show it donated $230,500 in 2016, well down from the previous year’s gifts of $1,304,500. Donations have since fluctuated, but more recently, as described below, Roshan awarded gifts of one million dollars or above to two universities.

Named for the Persian word meaning “enlightened; bright and clear,” Roshan is registered as a private foundation in the U.S. and is funded by the Omidyar Group, the philanthropy of Pierre and his wife Pam. Roshan sponsors activities and programs that focus primarily on the preservation, transmission, and study of Persian culture. The Institute develops initiatives that provide support for partnerships with other nonprofit organizations and institutions such as schools, universities, libraries, museums, and private sector donors who share its goals in support of Persian culture.

Elahe Omidyar Mir-Djalali, founder and chair of RCHI |

Pierre Omidyar’s mother, Elahe Omidyar Mir-Djalali, is founder and chair of RCHI. She holds a Ph.D. in Persian linguistics from the Sorbonne, University of Paris VII. Before becoming president of Roshan in 2000, she was a visiting scholar at UC-Berkeley from 1992 until 2000. Her curriculum vita lists thirteen articles or chapters, none more recent than 1994, on topics ranging from linguistics to Tehran’s building code. Pierre serves on the board of directors.

Pierre’s parents met in Paris, where their parents sent them in the early 1960s in order to attend French universities. Although he was born there in 1967 and named Parviz, Pierre moved with his parents to America when he was six so that his father, who had obtained a medical degree, could serve his residency in urology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. His mother, who raised him in the U.S. after his parents’ separation, was herself raised in a Sufi household in Iran. Pierre has been publicly silent about his birth religion, although he is listed on some Muslim websites as of Muslim ancestry. He is now a follower of the Dalai Lama and practices Buddhism. Pierre earned a degree in computer science from Tufts University in 1988 and in 2005 donated $100 million to his alma mater, the largest gift in its history at the time, to found the Omidyar-Tufts Microfinance Fund. Forbes estimates his January 2020 net worth at $13.2 billion.

Roshan is but a small piece of Pierre Omidyar’s vast empire of philanthropic concerns. The principal funding vehicle for his philanthropies is the Omidyar Group, the umbrella organization for Pierre’s giving. Within the byzantine web of organizations dedicated to a wide variety of causes is the Omidyar Network, which has donated $1.64 billion to various entities since its inception in 2004. Among the Network’s areas of interest are civic, technological, agricultural, educational, financial, and other projects. Many of them are apolitical, although some are clearly progressive.

The Omidyar Network contributed $100 million to support “investigative journalism, fight misinformation and counteract hate speech around the world.” Its bias is not immediately obvious. The Anti-Defamation League, the pro-Israel New York organization devoted to fighting anti-Semitism worldwide, has been one recipient, demonstrating Omidyar’s willingness to support non-leftist, pro-Israel causes. The ADL will use the Omidyar money to build “a state-of-the-art command center” in Silicon Valley to combat the growing threat posed by hate online.

Several recent grants have opened Omidyar’s political leanings to scrutiny.

But several recent grants have opened Pierre’s political leanings to scrutiny. Through his project First Look Media, he funds The Intercept, a virulently anti-Israel, far left online magazine founded in 2014 whose co-founding editor, Glenn Greenwald, in 2013 published classified documents stolen by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden and is an ardent supporter of the BDS movement. From 2007 until 2014 the Omidyar Network was among the largest donors to the Sunlight Foundation, which in turn funds Democratic activist George Soros’s Open Society Foundations along with other recipients of Soros’s money, including the Tides Foundation and the Brennan Center for Justice, both of which support leftwing undertakings.

Yet Omidyar’s largess isn’t limited to the political left. Among his grantees is GOP insider Bill Kristol, former editor of the now-defunct Weekly Standard and present editor of The Bulwark, a right-of-center publication that opposes Donald Trump. That the same philanthropist would simultaneously support publications that vilify and defend Israel is rare, if not unique. It demonstrates Omidyar’s focus on funding opposition to President Trump.

Roshan Institute: Preserving – and Politicizing – Persian Culture

With regards to the Roshan Institute, studying grantees’ academic background is more productive. As this report on Roshan demonstrates, Omidyar’s investments in exploring and preserving his homeland’s cultural heritage via grants to U.S. universities follow the pattern of his larger philanthropic activities. Many are laudable attempts to support the study of the ancient, medieval, or modern artistic, linguistic, and cultural achievements of Persia’s rich history. Others, however, resemble the biased, politicized scholarship so common in American academe in general, and Middle East studies in particular.

For all its good work, Roshan also funds work biased against America and the West.

Until this study, Roshan’s biases have gone largely unnoticed. This low-profile results from Roshan’s deliberate strategy of avoiding a high level of scrutiny by media and off-campus watchdog organizations. This study demonstrates that, for all its good work, Roshan also funds work biased against America and the West.

For example, RCHI chose to link to conspiracy-mongering sites on its resource page, such as Top Documentary Films. While its disclaimer renounces responsibility for third party websites, the decision to link to these was a poor one.

On Top Documentary Films one finds blatant pro-Iranian regime propaganda. The documentary Iran (Is not the Problem), attempts to whitewash the Islamic Republic’s responsibility in accelerating regional destabilization. Other films promote baseless conspiracies: The Anatomy of a Great Deception on Al-Qaeda’s September 11th attacks, and False Flag Hoaxers, which promotes mass shooting conspiracy theories. The institute was contacted several times for comment and finally responded begrudgingly (November 20, 2018) by removing the link and denying any affiliation with the films mentioned.

Roshan’s reply falsely claims no names or affiliations were included in this author’s inquiries, as the contact form on their site requires those fields for submission and they were duly completed:

Thank you for your interest in Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute. No reply was deemed necessary to your first email because we usually don’t reply to individuals who don’t introduce themselves (name and affiliation) and, most important, because neither Top Documentary Films (which we are not familiar with) nor any of the films listed in your emails are linked on our current website, which we update on a regular basis. You may wish to clear cookies on your computer each time before viewing any website, in order to get the most recent information. For easy reference, here’s the link to our webpage where we list relevant media [link updated 3-24-21]: https://roshan-institute.org/resources/.

Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute: Linguistics, Poetry, and Politics

Foreign money in the field of Middle East studies is nothing new. Saudi (and, more recently, Qatari) money have wrought havoc on the field and received significant attention for their years of funding anti-Western research and installing highly partisan scholars in key departmental positions. Not so RCHI. How did it maintain a low profile despite its years of donating to Persian studies?

The projects and recipients funded by Roshan span the gamut from apolitical to anti-American/Western, though the vast majority of projects avoid the pitfall of blatant pro-Tehran partisanship. We therefore first determined the nature of the foundation’s work: To what degree were its grants politicized or pro-Tehran? Did patterns emerge? A listing of RCHI activities and programs can be found in Appendix I. The report that follows examines whether it successfully lives up to its mission and its name, and whether Roshan’s legacy genuinely promotes principles that “uphold a community: compassion, tolerance, respect, and the desire to improve communication and understanding among people of diverse backgrounds.”

To keep the report a manageable length, we have examined those universities that have most benefited from RCHI’s generosity. Thirty-seven universities – thirty-two in the U.S. and five abroad – received grants from Roshan. So did twenty-four cultural institutions, from small Iranian studies organizations to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre. For this study, we examined eight universities, seven American and one British. Our goals include reaching an understanding of the motivations behind the institute’s choices and assessing the degree of compliance of grantees’ academic scholarship.

Some RCHI grantee projects whitewash the Iranian regime and its domestic and foreign policies.

For a fair assessment, both problematic and benign grantees were investigated in a given program (see Appendix I). As most grants appeared straightforward, we scrutinized a number of individual recipients whose publications and electronic footprints reveal politicized research. In particular, the report considers grantee projects that whitewash the Iranian regime and its domestic and foreign policies, including its anti-American, anti-Western, anti-Israel, and pro-Islamist/terrorist actions and statements.

On its site, Roshan states that “We recognize the importance of spirituality and honor a non-discriminatory, non-extremist approach to a healthy spiritual, mental, and emotional life"; and “We respect cultural diversity and those who support innovative and creative thinking.” Unfortunately, although most grantees are indeed apolitical, several highly partisan activities or publications by RCHI grantees indicate the contrary: their failure to uphold a non-discriminatory approach or respect cultural diversity is inconsistent at best with their stated goals and with the standards of rigorous, apolitical, unbiased scholarship.

RCHI defines its mission as fostering intercultural communication with host countries through a focus on:

- Establishing Persian studies programs at major universities;

- Awarding Fellowships and Scholarships for Excellence in Persian Studies;

- Working with other nonprofits that share RCHI’s mission in support of Persian culture and achieving a clear understanding of it through “community involvement and education.”

For RCHI, the emphasis in establishing programs and grant allocation is typically on the cultural rather than the political intents of the grantors. Yet not all grants, programs, or activities are equally transparent. For example, there are issues in the detail in the continuation of part XV, line 3a (990-PF) of Roshan’s 2016 tax return that reveals recipients who may not have been mentioned on the Roshan site. The reason for the possible discrepancy remains unclear. According to the returns grants total for 2016 was $230,500. A similar lack of transparency appears to exist on Roshan’s form 990 in 2018. Its total given for “contributions, gifts, grants paid,” part I, line 25, is $205,000 for the period ending June 30; yet the University of Arizona’s site announced a $1 million gift from Roshan on June 14, 2018. The grant does not appear on Roshan’s 2019 990, either.

This report covers Roshan programs at the eight universities that most benefited from Roshan’s generosity: the University of Maryland; the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Arizona, California State University at Fresno, California State University at San Jose, the University of California at Irvine, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and the University of Oxford. At Oxford alone, the grant went to an individual scholar rather than the entire program.

RCHI’s funding follows the recent trend of growth in Iranian studies and it has occurred almost exclusively at large state universities. In 2009, Howard Cincotta noted that growth in the traditional Ivy League strongholds for Persian and Middle East studies has been outpaced by newer programs at state universities. “In some cases, older institutions have shifted their focus into more specialized areas of scholarship — whether Islam or Shi’ism, Ottoman culture or pre-Islamic Persia.” One reason for this is the general trend of a dramatic increase in students studying non-European languages in the United States. In addition, Persian has benefited from the U.S. government’s designation as a critical language, a designation it shares with Arabic, Russian, Chinese, Hindi, Urdu, and Korean.

Maintaining a Low Profile

Roshan follows several strategies to remain out of the limelight, the better to avoid controversy in both politicized and apolitical projects. Most of its donations target departments or programs that are outside the politicized orbit of Middle East studies orthodoxy, even within universities with the highest number of virulently anti-American, anti-Western, and anti-Israel incidents. This steers clear of the level of investigation experienced by campuses that employ prominent professors who attract significant negative press for their radicalism. Roshan typically chooses to house its endowed chairs in departments of art history, music, Asian studies, or similar programs that do not normally receive much critical press attention.

Most RCHI grantee are outside the politicized orbit of Middle East studies orthodoxy.

Another aspect of this deliberate strategy to maintain a low profile,[1] until recently, is the low number of first-tier research universities among Roshan’s major grantees; higher profile universities received modest grants, often for dissertation or publication research or temporary exhibits. Other than Oxford and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, most recipients of significant grants (aside from Persian linguistics) are second-tier institutions whose lower ranking generally ensures a lower level of press and watchdog scrutiny. A sign that Roshan is increasingly willing to adopt a higher profile is demonstrated by its very large gift of $6 million to the University of Toronto, a major research institution. Whether this trend will continue is difficult to predict given the large fluctuations in Roshan’s year-to-year giving.

Still, as a result of past giving patters, the selection of grantees whose biased scholarship reflects poorly on the institute goes mostly unremarked. RCHI has made awards to self-proclaimed “activist scholars,” including Stephanie Cronin, Fatemeh Keshavarz, Simin Karimi, Leila Hudson, and Anne Betteridge, several of whom rejected their institution’s stance on academic freedom or supporting boycott and divestiture on the basis of nationality and religion. With their calls for boycott and unfettered support for discrimination against academicians of a single nationality (Israel) or those who support them, the selection of these professors demonstrates Roshan’s willingness to violate its stated principle to uphold “a community: compassion, tolerance, respect and the desire to improve communication and understanding among people of diverse background.” Therefore, despite Roshan’s stated policy to engage in proactive philanthropy “in which the donor takes a more responsible and involved role than that of merely providing funds to support programs and projects,” our evidence demonstrates that it does in fact support biased work at the expense of teaching and preserving Persian culture.

With its strategy of investing in individuals and programs on the periphery of Middle Eastern Studies, RCHI has managed to remain unnoticed by most higher education critics. Roshan and its board of directors follows a strategy that keeps a low profile in higher education and avoids drawing the attention unnecessarily of watchdogs.

Conclusion: Does Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute Live Up to Its Mission and Name?

Roshan funds many apolitical, culturally important undertakings, from the study of medieval poetry and art to support for archaeological projects, Persian language studies, and the Iranian diaspora. Yet, as the evidence below illustrates, it also funds politicized research and publications that deserve far greater scrutiny than they have heretofore received.

Its support has centered largely on pre-modern topics and researchers, which tend to be apolitical. Familiar sparks of politicization and partisan scholarship start to fly when funding is offered to recipients with a background and training in the modern Arab Middle East and research interests in so-called “intersectionality.” Consequently, the mission of cultural exploration is more likely to be sullied by the politics of Middle Eastern studies when research and community events center on modern Iran, Middle Eastern geopolitics, and U.S. foreign policy. A number of RCHI grantees illustrate in their public statements and publications the egregious problems that persist in that troubled field: analytical failures, the mixing of politics with scholarship, intolerance of alternate views, apologetics, and the abuse of power over students. Such problems have gained a near-stranglehold over American MES programs.

RCHI’s benign mission statement to support “cultural and educational activities that bring to light the richness and diversity of Persian culture” and to foster “community among Persian people and those interested in Persian cultural heritage” is therefore ultimately misleading. As the evidence below demonstrates, hidden within its many legitimate grants are unmistakably tendentious, highly politicized, even Islamist projects and individuals. Roshan should be called to account for its role in strengthening the biased status quo in Middle East studies.

Appendix I: Eight Select Universities Supported by Roshan

The University of Arizona

The Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies offers MA, PhD, and minor degrees. |

In 2016 Arizona’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences received a $2 million commitment from RCHI[2] to establish the Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies. Offered by the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, the gift elevated it to among the largest of its kind in the United States. The grant from RCHI is intended to advance humanistic and social science research in the study of Persian and Iranian society, culture, and history, and to bolster the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences’ scholarly depth in Iranian and Persian studies. It supports the program’s components, including a newly endowed faculty chair and an endowed professorship, master’s and doctoral programs currently under development, various programmatic activities, and a Fellowship for Excellence in Persian and Iranian Studies. Arizona indicated on its website that it had already received the first $1 million of the grant, though it does not appear on the institute’s 2016 returns. Some dissertation titles and area studies funded through this Roshan commitment are eligible to receive funding for multiple academic years.

According to the University of Arizona, RCHI funds will also be used to:

- Expand UA’s connections with academics in Iran;[3]

- Support academic programming on such topics as ancient Iranian languages and religion, Iranian Sufism, and Iranian arts and literature.

Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian and Iranian Studies recipients produced papers such as “Aiding Israel: How the Iranian Media Bolsters Israeli Pinkwashing,” by Ana Ghoreishian (2011 - 2012). Promoting deliberate inaccuracies such as Israel’s “pinkwashing” of its alleged persecution of the Palestinians by diverting attention to the freedoms enjoyed by the LGBT community in Israel clearly violates Roshan’s stated mission of upholding community: “a community: compassion, tolerance, respect, and the desire to improve communication and understanding among people of diverse background.”[4] It equally violates the standards for apolitical, rigorous, and unbiased scholarship to which all academic work should be held.

Similarly, as the former and long-time home of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA), whose politicized leadership allows its members to embrace the boycott, divestiture and sanction movement against Israeli academics (BDS), UA’s goal to expand connections with a heavily sanctioned country such as Iran embroils the institution in a controversial double standard: one for Israeli academics, the other for the rest of the world. In contradistinction to MESA’s violations of principles of good scholarship, Roshan’s support for a 2006 visit by Shirin Ebadi to UA illustrates the institute’s support for fact-based research. Ebadi, a distinguished Visiting Faculty in Human Rights, was invited to teach a graduate course on “Islam and Human Rights” at The Center for Middle Eastern Studies. This intensive course investigated the real and perceived tensions between Islam and human rights based on Ebadi’s experience as an Iranian judge, lawyer, and activist.[5]

In June 2018, UA received a $1 million grant named for Pierre Omidyar’s mother: the “Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Professor of Persian Language in honor of Mir-Djalali, a renowned linguist and the founder of Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute.[6]” The gift is not noted on Roshan’s 2018 990. The first holder of the chair funded by the grant is, Narges Nematollahi, an assistant professor of Persian language in the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies and the Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies[7]. Her work, which deals principally with Persian grammar, is refreshingly apolitical.

The same can’t be said for the Roshan-sponsored Second North American Conference in Iranian Linguistics in April 2019, which featured as its keynote speaker the vehemently anti-Israel, anti-U.S. Noam Chomsky, who joined the faculty of UA in 2017 after retiring from MIT. On the conference’s first day, Roshan congratulated UA for “successfully organizing” the event.[8] Chomsky delivered two lectures, one on linguistics, his academic specialty, and the other on U.S.-Iran relation. Predictably, Chomsky’s presentation on Iran whitewashed the Iranian regime by failing to mention its terrorist activities worldwide, including its support for Hezbollah and Hamas. Iran can be trusted to abide by its promises not to acquire nuclear weapons and will adhere to any treaty it signs, while America and Israel are responsible for instability in the region. Chomsky praised Trita Parsi, founder of the National Iranian American Council (NIAC), accused by Ian scholars and members of the Iranian diaspora of lobbying for the Ayatollah. Roshan’s praise for a conference hosting a Chomsky, whose comments were entirely predictable, demonstrates its willingness to turn a blind eye to Tehran’s human rights violations and sponsorship of terrorism.

Professors of Note

Kamran Talattof |

Kamran Talattof is the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Chair in Persian and Iranian Studies and the founding chair of Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies at the University of Arizona. Among his publications are The Politics of Writing in Iran: A History of Modern Persian Literature, the co-edited book The Poetry of Nizami Ganjavi: Knowledge, Love, and Rhetoric, and Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of a Popular Female Artist. His writings and lectures do not reveal a pro-regime bent. To the contrary, some of his review articles critique the patriarchal Iranian social conventions and praise the subversion of the male-dominated literary style in pre- and post-revolutionary Iran. Similarly, his co-authored book Contemporary Debates in Islam: An Anthology of Modernist and Fundamentalist Thought,[9] examines the damaging and dangerous aspects of Islamic fundamentalism. Among the key issues separating modernism and fundamentalism covered in this anthology of texts are: gender relations; political theory; legal reform; attitude toward science; treatment of non-Muslims; and economic concepts. In addition, the book covers conspiracy theories in Islamic fundamentalism, and historical criticism’s role in modernism. The issue of conspiracy theories is relevant only to Islamic fundamentalism, whereas historical criticism is relevant to modernism.

Other than issues in Islamic thought and the politics of writing, Talatoff has poured much of his energy (2008 through 2013) into a Persian textbook project entitled Modern Persian: Spoken and Written (Volumes 3, 4 and 5), supported and funded by the Roshan Institute. (The first two volumes in the series, which Talatoff co-authored had a different sponsor). The series adheres to Roshan’s mission, as it is designed to teach elementary and intermediate levels of Persian for college students or independent learners.

Anne Betteridge |

Anne Betteridge’s background and research interests are more tendentious. Betteridge is Associate Professor of Iranian Women and Culture in the department of Near Eastern Studies and director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES). She was the executive Director of the Middle East Studies Association of North America (MESA) from 1990 until 2002. As part of the organization’s leadership for over a decade, Betteridge promulgated a myopic view of the Middle East that ignores all the non-Israel related rivalries, including Turkish vs. Kurdish, Islamists vs. modernist secularists, nationalists vs. Islamist dictators, and Sunnis vs. Shiites. The one issue that consistently dominates MESA is Israel, and a scholar’s stance on Israel is invariably a litmus test. As Middle East historian Martin Kramer put it: “For MESAns, the Palestinians are the chosen people.” Representing over 3,000 members in the field (one hesitates to call them all scholars), MESA has become increasingly irresponsible and anti-Semitic over the years. It is no surprise that it has supported the anti-Semitic BDS movement by formally recognizing it as “legitimate form of non-violent political action.” As a long-serving executive director, Betteridge bears great responsibility for the organization’s increasing politicization.

Betteridge’s research interests focus on Iranian culture, particularly women and ritual. She lived in Iran from 1974 until 1979 conducting fieldwork and has made three visits to Iran since then. At Arizona, she teaches courses related to ethnography of the Middle East, the study of Middle Eastern women, and Iranian culture and society. Betteridge has written surprisingly little since the 1990s besides reviews, edits, and citation by others. A search on JSTOR for articles or chapters authored by her yields only five items, the most recent of which was a 2011 obituary.[10] Even a broader web search yields only four additional titles published between 1986 and 2002.[11] Such a thin list is peculiar for a researcher of her stature, and particularly in light of her position as the director of CMES.

Leila Hudson |

Leila Hudson is an associate professor of Modern Middle East Culture and Political Economy. Like Talattof and Betteridge, Hudson is not listed by AMCHA as a BDS faculty academic boycotter, nor was she a signatories to the 2014 BDS call for the academic boycott of Israel. However, Hudson’s courses and publications have a definite pro-Palestinian bent. Her review of Zaki Chehab’s book Inside Hamas[12] reveals this debilitating pro-Palestinian predisposition. Chehab is Palestinian, familiar with cultural norms and has no language barrier. While Hudson’s critique of him is gentle, it exposes a typical ignorance of facts on the ground which inevitably produces imbalanced analysis. Regarding one of Chehab’s female subjects in Inside Hamas, Hudson says: "... in Chehab’s treatment she morphs into a frightening caricature of the mother of a suicide bomber, and wittingly or not, she and Chehab effectively captivate the reader with the image of a mother who is a little too eager to have her sons meet their heavenly brides.” Hudson shows in her critique that she is unwilling to see reality, in this case that of Gaza under Hamas, even through the eyes and language of a Palestinian journalist, because what he is expressing does not support the pro-Palestinian biases typically pushed in Middle Eastern studies.

Her bias precludes her from seeing that mothers in Gaza and elsewhere in the Middle East truly are at times only too eager to have their sons meet their heavenly brides. Even when described by an insider, Hudson’s unwillingness to recognize the truth is, using her own words against her, “a culture of counter realism.” She relates this idea in a 2005 article where she accused all think tanks and scholars of strategic studies of having “substituted strategy for discipline, ideological litmus tests for peer review, tactics and technology for cultures and history, policy for research and pedagogy, and hypotheticals for empiricals.” In this vitriolic and unintentionally ironic attack on think tanks, Hudson levels accusations that, with nearly a decade and a half of perspective following the publication of her article, seem laughable. She is describing Middle Eastern studies for what the field has become in the post-Edward Said era: “an uncomfortable blend of grand strategy, low tactics, imaginative gymnastics, ideologically motivated private funding (on average 10 times greater per institution than the total public investment in Middle Eastern Title 6 [sic] centers), and a studied avoidance of Middle Eastern human realities.”[13] In her broadside, Hudson focuses in particular on Martin Kramer’s Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America and condemns the work of Daniel Pipes and Campus Watch. Her above statement on “ideologically motivated private funding” is unintentionally ironic in light of the RCHI‘s generous private funding to establish the Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Persian and Iranian Studies at the University of Arizona.

Simin Karimi |

Another Roshan recipient, Simin Karimi, is Professor of Linguistics with appointments in the Cognitive Science Program, the Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching (SLAT), the joint Program in Linguistics and Anthropology, the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies (MENAS), and the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. She is also part of the faculty at Roshan Graduate Interdisciplinary Program for Persian and Iranian Studies. Karimi has made her anti-Israel views explicit several times, including as a signatory to a 2010 letter to the International Society of Iranian Studies (with the unfortunate acronym ISIS) written in response to the society’s intention to host a faculty member from Ariel University, an Israeli institution in the West Bank. Her stance contradicted Arizona’s formal position that rejects the call for a boycott of Israeli academics: “Three U.S. scholarly organizations (AAU, APLU, ACE) and a number of their member institutions have opposed a boycott of Israeli academic institutions. The University of Arizona agrees with the position taken by AAU and APLU and stands in support of academic freedom.” Although Karimi is not on the list of supporters of the US campaign for the academic and cultural boycott of Israel, she doesn’t appear to share UA’s or RCHI’s support for academic freedom and intercultural communication.

University of Maryland- College Park (UMD)

Roshan Inst. at U. Maryland “aspires to be the premier center for the learning, understanding, and appreciation of Persian culture in the United States.” |

Roshan Institute provided substantial funding to advance Persian studies at the University of Maryland and to establish the Roshan Institute for Persian Studies. In 2007, Roshan made a $3 million leadership gift to the University of Maryland College Park Foundation. A year later, a major and a minor in Persian language and studies were developed and the existing Center for Persian Studies expanded into the current Roshan Institute for Persian Studies, with its academic programs, research, and scholarships. Roshan Institute’s named endowments at UMD are as follows:

- Roshan Institute Chair in Persian Studies;

- Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian Studies;

- Roshan Institute Scholarship for Excellence in Persian Studies;

- Roshan Institute Endowment for Persian Programs;

- Roshan Institute Lectureship;

- The Mir-Djalali Cultural Events Series;

- The 2015 launch of an undergraduate Persian Studies journal, Roshangar. Founded as a biannual academic publication, the journal is designed and run by a group of undergraduates under the guidance of former Roshan Institute Fellow and current visiting assistant professor Ida Meftahi. Accompanying the peer-reviewed journal is the Roshangar website, featuring film and book reviews, interviews with scholars and artists, and highlights of local Persian events.

A believable explanation for Roshan’s strategic selection of UMD to receive funding is found on UMD’s Flagship page: “Our program’s proximity to the national capital and its access to a sizable and vibrant Iranian-American community in the greater DC area provides students with internship opportunities to develop professional skills and allows for a rich calendar of cultural events.”

Roshan’s mission calls for cultural exploration and funding events, area studies, or dissertations. While it is noteworthy that RCHI has supported grantees from Israeli universities, other funds have supported politically charged topics by scholars whose anti-Western, anti-Israel record is undeniable, as the following examples illustrate:

- A 2017 lecture by Miriam Cooke, Braxton Craven Professor of Arab Cultures at Duke University, on “Dancing in Damascus: Creativity and Resilience in the Syrian Revolution.” Cooke’s record of politicized scholarship and attacks on ideological opponents illustrates the egregious problems that persist in the field of Middle East studies. This is precisely the kind of an ideological stranglehold over MES departments that Roshan should seek to avoid.

- A 2016 lecture and book signing by Hamid Dabashi, Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University,on his book, Persophilia: Persian Culture On The Global Scene. His crude anti-Semitism is well known and extensively documented. Calls for his suspension from Columbia erupted in June, 2018 in light of his Facebook posts reflecting common anti-Semitic canards calling American Jews “diehard Fifth Column Zionists working against the best interests of Americans.” Furthermore, Dabashi’s stated views on the U.S. and Israel reflect an egregious anti-Western bent: “the Middle East is under U.S./Israeli imperial domination” and America is an “empire without hegemony” engaged in a “monopolar imperial project.” He has repeatedly excused the mullahs’ actions in Tehran as “indigenous” and “not like the gang of European Zionists who descended upon Palestine and stole it from its rightful inhabitants.” For Dabashi, the Jews are always to blame.

Earlier events sponsored by Roshan include a conference on human rights in Iran and a lecture on the Iranian revolution. Both show professional academic engagement rather than biased programming:

- A 2010 international conference, “Toward a Culture of Civil Liberties, Human Rights, and Democracy in Iran.” It examined the emergence and evolution of a non-violent and nonpartisan popular demand for advancement of civil liberties and human rights in Iranian society. A number of the participants are recipients of Roshan grants, including one of its main organizers, Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak.

- A 2010 lecture, “The Iranian Revolution After 30 Years: Domestic Challenges and Regional Implications,” presented by David Menashri, director at the Center for Iranian Studies at Tel Aviv University.

Despite welcoming pro-BDS professors such as Cooke and Dabashi to its conferences, UMD has formally rejected demands to boycott Israeli academe. The formal position was stated by the school’s president and its senior vice president/provost:

We firmly oppose the call by some academic associations—American Studies Association; Asian-American Studies Association—to boycott Israeli academic institutions. Any such boycott is a breach of the principle of academic freedom that undergirds the University of Maryland and, indeed, all of American higher education.

Faculty, students, and staff on our campus must remain free to study, do research, and participate in meetings with colleagues from around the globe. The University of Maryland has longstanding relationships with several Israeli universities. We have many exchanges of scholars and students. We will continue and deepen these relationships.

In the United States, we can disagree with the governmental policies of a nation without sanctioning the universities of that nation, or the American universities that collaborate with them. To restrict the free flow of people and ideas with some universities because of their national identity is unwise, unnecessary, and irreconcilable with our core academic values. (Wallace D. Loh, President, Mary Ann Rankin, Senior Vice President and Provost).

Fatemeh Keshavarz |

Professor Fatemeh Keshavarz is Roshan Institute Chair in Persian Studies and director of Roshan Institute for Persian Studies since the fall of 2012. She is also director of the School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures since August 2014. Earlier Keshavarz taught at Washington University in St. Louis for over twenty years, where she chaired the Department of Asian and Near Eastern Languages and Literatures until 2011. In her biography on the UMD site she describes herself as “a scholar, award-winning author, poet and activist.” Keshavarz’s activism comes through in her writing, which can lose its critical distance from her subject with overzealous attempts to dismantle criticism leveled at the post-revolutionary Iranian regime. This is evident, for instance, in herJasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran, where she takes Azar Nafisi’s comments in Reading Lolita in Tehran (New York: Random House, 2003) out of context in order to accuse her of suggesting that Islam and feminism are contradictory.[14] This highlights Keshavarz own defensive stance regarding the mullahs’ regime, as she lashes out at Nafisi for daring to reveal, from her perspective, the hypocrisy of revolutionary Iranian ideology. Her attack on Nafisi’s memoir was expressed in a 2009 lecture at Marlboro College, where her book, Jasmine and Stars — free copies of which were given to attendees — was presented as a “pro-Islamic Republic” contrast to Nafisi’s perspective and personal experience. Given the positive reception for Nafisi’s book, Keshvaraz’s attacks are particularly revealing and insidious. In presenting her book as a response to Nafisi’s personal experience, she defends a brutally oppressive and corrupt regime with blood on its hands.

Ida Meftahi |

Ida Meftahi, former Visiting Professor of Contemporary Iranian Culture and Society at the School of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, is a historian specializing in modern Iran with a focus on the intersections of politics, gender, and performance. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto’s Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations. Meftahi’s short publication record[15] illustrates her embrace of intersectionality[16] in Iranian studies in particular, and more broadly in the field of Middle East studies. Intersectionality introduces serious problems, especially in highly politically charged area studies like that of the Middle East, by reducing human beings to political abstractions. This reduction produces severely flawed research because it flattens the complex human experience and therefore cannot satisfactorily describe reality. As Chloe Valdary notes, “the human experience is complex and multifaceted and deeper than the superficial ways in which intersectionalists describe it.”[17] Ali Reza Abasi is Associate Professor of Persian with expertise in applied linguistic and research interests in second language writing, language and power, and conversation analysis. Abasi is also the associate director of the University of Maryland Persian Flagship Program. While one of his indicated research interests is language and power, the only publication in his electronic footprint so far is: “Content-Based Persian Language Instruction at the University of Maryland: A Field-Report,” National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages(JNCOLCTL), Vol. 15 (Spring 2014), 73-98.

University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM)

A grant from Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute supported the establishment of a Persian Language, Linguistics, and Culture Program (2013 to 2018) at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, in the College of Languages, Linguistics, and Literature. It provided support for a Roshan Institute Instructor in Persian Language and Culture, a Roshan Institute Fellowship in Persian Linguistics, Language Acquisition and Applied Linguistics for students pursuing Ph.D. degrees in Linguistics and Second Languages Studies, and a Roshan Institute Fellowship for Persian Language and Culture for graduate students enrolled in Persian language and culture courses. As in the case of other RCHI-funded projects, this program was intended to foster a better understanding of Persian language, linguistics, and culture. This state school was an obvious target for the Omidyars, who call Hawaii home. It is unclear whether the program at UHM is still viable. UHM was contacted repeatedly but representatives did not make themselves available for comment.

Professors of Note

Ladan Hamedani |

Ladan Hamedani was one of only two Roshan instructors in Persian language and culture at the Indo-Pacific Languages and Literatures (IPLL) Department within the College of Languages, Linguistics, and Literature (August 2013 to August 2018). Hamedani received her Ph.D. in Linguistics from the University of Ottawa, Canada, in 2011. Her background is solidly in general linguistics and her research interests are Persian language, Persian syntax, testing, translation, literature, and culture, as well as pedagogy and second language acquisition. Her previous work experience included a stint as Persian lecturer at McGill University and as a faculty member at Islamic Azad University, Faculty of Foreign Languages, in Tehran. Oddly, Hamedani has a meager electronic footprint and no known publications. She appears to have avoided engaging in anything political. The other staff member of the Roshan Persian program was Maseeh Ganjali. Ganjali was born in Iran, immigrated to the U.S. at the age of thirteen, and received a Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute Fellowship to travel and conduct research in Iran in 2011. His research interests include Persian literature, culture, and heritage, with a strong focus on performing arts in Iran. Ganjali has an overly apologetic view of Iran and its government, even if he is not overtly supportive of it. In a short interview for Flux,[18] he says:

"[Iran has] a very two-dimensional portrayal in media. It’s not the Iran I know. It’s not to say that Iran’s not limited in some ways, but the complexity of it all is always missed in the media here. It’s still a young government. It’s sort of a new country with a lot of young people. Majority of the population is under 30 years-old. So that means they’re figuring a lot of things out, and in that process, not everything is going to be fantastic. I miss Iran’s poetry and the performing arts. Poetry was always a part of my life, a part of our culture.”

Claiming Iran has a “young government” conveniently omits the regime’s bloody history of oppressive dictatorship and foreign aggression, including its long history of sponsoring terrorism worldwide. While these crimes shouldn’t be laid at the feet of the populace, Ganjali speaks of the revolutionary government as if, given time, it will evolve into a peaceful, democratic regime.

In 2011 and 2012, Ganjali was awarded a Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian Studies to support a photography series about the Parde-khani and Kheymeshab-bazi performance traditions of Iran. His first exhibit, “Common People, Common Places: Photographs from Iran,” was showcased at the UH Manoa’s Hamilton Library during spring and summer 2012. His second exhibit, “Zoorkhane: House of Strength,” was displayed at the University’s Hamilton Library Alcove during summer and fall 2014. In December 2016, Ganjali received a Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian Studies to conduct field research on traditional Iranian puppetry, as part of his Ph.D. studies. He has gone back to Iran several times, working at the University of Tehran (UT) with the express purpose of fostering cooperation and close working-relationship with the Iranian university. While the goal may be constructive, fostering a relationship with academic institutions in a sanctioned country like Iran is dangerous. UT’s political and social role in Iran has been pronounced, to such an extent that in 2005 a senior Islamic scholar with overt ties to the regime became the chancellor. That UT is infiltrated with pro-regime lackeys is certain, although some students have protested (and been violently suppressed).[19] Its central place in Iranian elite circles has made it the setting for many political events and cultural works, both for and against the mullahs’ regime.[20]

San Jose State University (SJSU)

A 2015 Persian Studies Program lecture featured Prof. Fereshteh Dianat, second from left, of Alzahra University, Tehran. |

Starting in 2013 the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute supported a three-year pilot program in Persian Studies at San José State University. The stated goals and vision of this grant,[21] for which a dollar figure is not available, was to draw on the intellectual and cultural resources of SJSU and the Silicon Valley community to offer an interdisciplinary approach to understanding Iran, Persian culture, and language, including an appreciation and study of other Persian-speaking communities in the Iranian Diaspora. Among the initiatives supported were research projects by SJSU faculty, graduate fellowships, undergraduate scholarships and assistantships, a Roshan Institute lecture series, and cultural events. SJSU is a regional university rather than a major research institution. It appears to be strategically chosen to more fully engage not simply the academic community of a middling university, but the larger Silicon Valley. As America’s principal technology corridor filled with highly influential industries and individuals, Silicon Valley offers a rich target. Moreover, a second or third tier school such as SJSU allows Roshan to wield its influence while not calling undue attention to itself.

Recipients of the Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian Studies at SJSU published material that does not strictly adhere to Roshan’s mission of Persian cultural exploration. Examples include: Sadegh Foghani, “Diaspora Iranian Engineers in the US” (2015); and Sarah Aghazadeh, “US policy and diplomacy toward Iran under the Obama administration” (2015), an M.A. thesis that claims the “Israel lobby” undermines America’s ability to form stable relations with Iran.[22] However, such titles do offer an interdisciplinary approach to understanding Iran and the Iranian diaspora.

In addition, RCHI has funded lectures and events at SJSU organized through the Persian Studies Program. Guest speakers included Juan Cole (University of Michigan), whom Gary Fouse called among the “chief apologists for Islamic extremism in the academic world.” Cole, with his highly partisan and unprofessional attacks on intellectual opponents, has been thoroughly researched by Campus Watch, and his tendentious public statements need not be re-examined here. RCHI’s Persian Studies Program invited Cole to give a keynote public address at a lecture, entitled “Engaging Iran after the Nuclear Agreement.” As this illustrates, Roshan’s mission of cultural exploration gets muddled in the politics of Middle Eastern Studies when a proposed event focuses on modern Iran, Middle Eastern geopolitics, and U.S. foreign policy, or when a keynote speaker has called on the FBI to investigate scholars who disagree with him. Cole has also unsuccessfully sued the CIA and FBI in 2011 over his denied appointment at Yale in 2006.

Professors of Note

Shahin Gerami |

Shahin Gerami is a professor of women’s studies and Director of Persian Studies. She holds a law degree from the University of Tehran and a doctorate in sociology from the University of Oklahoma. Her research and activism have involved different facets of gender inequality in displaced populations, religiously sanctioned sexism, and political profiling of Muslim men. Gerami’s most extensive research on gendered religious fundamentalist movements was carried out -- albeit with significant methodological and substantive flaws[23]-- in her 1996 Garland Press book titled Women and Fundamentalism: Islam and Christianity. Gerami’s research and activism do not readily suggest a pro-Iranian regime bias.[24] For instance, in a 2013 lecture funded by Roshan and hosted by the Persian Studies Program at SJSU, Gerami took on the issue of resistance to the Iranian regime in the context of “Iranian Women Occupying Facebook: Identity and Resistance.” In addition, her review of Nelly Lahoud’s “The Jihadis’ Path to Self-Destruction”[25] illustrates a mostly neutral tone toward this distinguished author, who is a former associate professor at the department of social sciences and senior associate at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center, and current fellow at New America. In this case, neutrality is a welcome finding, though it should be expected from all scholars in their professional conduct. It must be noted that the New America is partly funded by the Omidyar Network, which illustrates the depth and breadth of Pierre Omidyar’s philanthropic influence. In her online SJSU biography Gerami notes she is conducting a survey of Iranian Americans and their attitudes toward Iran. She is also co-directing a survey since 2012 “Iranian-American Voices in Silicon Valley: Evolution of a Community.” For the 2012, survey Gerami compiled and analyzed data, building on the 2010 Census information where, for the first time, Iranian Americans were asked to identify themselves and answer direct questions about their experience as ethnic Americans. It would be useful to publish the data as well as the questions asked on the survey, as it would shed light on Gerami’s thinking and highlight trends in the Iranian-American community in Silicon Valley.

The “Iranian-American Voices” project is a pilot program started in March 2012 and funded by Cal Humanities through the Iran-America Project and its Community Stories program. The project seeks to document and share the stories of the Iranian diaspora community in Silicon Valley in order to better understand the experiences of over thirty years of Iranian-American presence this region and to share those stories in an online format.

California State University, Fresno

In what appears to be the overarching theme of RCHI’s modus operandi - targeting state schools that stay out of the limelight - the institute has supported the development of Persian Studies at California State University, Fresno for over a decade. In 2007 the Roshan Institute Scholarship for Excellence in Persian Studies was created within the College of Arts & Humanities to foster and develop course offerings in Persian Language and Culture Studies. A year later in 2008, a grant was provided by Roshan for programmatic activities in Persian and Iranian Studies. By 2009 seventeen scholarships were granted and, in 2010, the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute Endowed Professorship was established to support a faculty member who will contribute to the development of the Persian Language and Culture Studies program in the College of Arts & Humanities. In 2011 the PARSA Community Foundation contributed $200,000 toward an endowment at California State University, Fresno as part of a series of grants promoting Iranian studies programs throughout North America. RCHI matched the PARSA grant, which was in addition to a previous $500,000 Roshan grant for a total $900,000 endowment.

To date, Roshan has granted scholarships to over one hundred recipients at CSU Fresno in order to encourage the study of Persian and Persian culture. The vast majority of recipients are of Iranian heritage, which speaks to the size of the Iranian community in this and other locations selected by Roshan.

Partow Hooshmandrad |

According to Roshan’s 2016 tax returns, CSU Fresno received one of the highest donations that year from the institute ($50,000), second only to UNC Chapel Hill ($75,000). The purpose of grant/contribution listed on the return is “Middle East Studies and Persian Programs.” Partow Hooshmandrad of the department of music held the endowed professorship initially. Her background in Iranian music fit Roshan’s modus operandi of funding scholars who are promoting a wide array of Iranian cultural achievements. Hooshmandrad is a scholar and musician who specializes in the devotional practices of the esoteric sect centered in Iranian Kurdistan, Ahl-i Haqq,[26] including musical repertoire, texts, and rituals, as well as Iranian classical music.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Carl Ernst accepted an academic award from the virulently anti-Semitic Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2008. |

In 2015, RCHI funded the Roshan Institute Professorship in Persian Studies at the Department of Asian Studies. This endowment marked the first Persian Studies endowed professorship at UNC. Two years earlier, Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute had established the Roshan Institute Fellowship for Excellence in Persian Studies. This includes admissions recruitment fellowships that are awarded to support graduate students whose research focuses on Persian studies applying to a doctoral program at UNC. Roshan fellowships also support current UNC graduate students through summer research awards for travel, reproduction of archival materials, purchase of research-related materials, and other expenses related to graduate research. In 2016 Roshan funded the Persian Arts Series with a $75,000 grant. It is noteworthy that UNC Persian Studies program is housed in the Department of Religious Studies, and directed by Carl Ernst, who is also the co-director of the Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations. Though located in different UNC departments, there is little doubt Ernst was instrumental in securing and filling the first Roshan professorship in Persian studies within the Department of Asian Studies. In this sense the Roshan endowment is providing funds and support for Ernst’s program. His travel to Tehran in late 2008 to receive an award for his academic work from Iran’s then-president, the virulently anti-Semitic Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, sounds the alarm regarding his working relationship with the sanctioned Iranian regime and likely violations of the Title VI program.

Professors of Note

Claudia Yaghoobi |

Claudia Yaghoobi was selected as the inaugural Roshan Institute assistant professor in Persian Studies in July 2016. She received her Ph.D. in comparative literature with an emphasis in feminist studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and was previously assistant professor of international literature at Georgia College and State University. Yaghoobi teaches Persian language and culture courses and is the UNC Persian Studies Program Coordinator. The emphasis on secular and Islamic feminism in her research is evident in her body of work, which reveals her political and intellectual commitment to secular feminist scholarship.[27] She teaches classes on women’s movements in Iran, Iranian post-1979 cinema, gender and sexuality in Middle Eastern literature, Iranian prison literature, and wars and veterans in Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In some of her writings she refers to the Iranian regime’s aim of offering a propagandist definition of events,[28] such as the Iran-Iraq war. For instance, she praises the exposition of government propagandist works which promoted the Iran-Iraq war as “a war of defense against the non-sacred, non-Islamic Iraq.”[29] In other writings she adheres to the standard politicized Middle Eastern studies clichés that the “Westernizing colonizing mission” portrays Muslim women as “primitive” – a charge often used to deflect criticism of the treatment of women in Muslim lands. However, she also expresses her agreement that these depictions are often “complicated” when Muslim act in ways that reinforce such stereotypes.[30]

St. Antony’s College at the University of Oxford

Stephanie Cronin |

Stephanie Cronin, outspoken supporter of the BDS movement, has received multiple research fellowships from Roshan during her tenure as an Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Research Fellow at Oxford. Previously, as a fellow at the Iran Heritage Foundation, University of Northampton (Northampton, UK), she was a signatory to a 2007 boycott letter by the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI), as well as a 2009 boycott letter by UK academics. In 2015, Cronin, along with ten of her Oxford colleagues, signed an open letter in support of the boycott of Israeli academic institutions. These calls for an academic and cultural boycott of Israeli academics stand in contradiction to St. Antony’s stated mission to:

- Promote interdisciplinary scholarship on Turkey, Iran, Israel and the Arab states of the Middle East and North Africa from the nineteenth century to the present day.

- Serve as a bridge between Europe and the Middle East, encouraging the exchange of students and researchers from across the region.

Roshan awarded Cronin a three-year Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Research Fellowship (2018 to 2021) in support of a new project entitled “Modern Iran: A Transformational History,” and the establishment of a new, not-yet-launched book series on historical studies of Iran and the Persian world at Edinburgh University Press. Previously, the RCHI had awarded her a three-year visiting research fellowship (2015 to 2018) in support of teaching in modern Iranian history, organizing an international conference, and conducting research for her forthcoming book, Iran: A People’s History. The international conference, titled “The ‘Dangerous Classes’ in the Middle East and North Africa” was held on January 26, 2017, at St Antony’s College, with ten speakers and more than 100 participants. As Cronin was upfront about her position on academic and cultural boycott of Israel and her embrace of partisan research, RCHI was clearly aware where the foundation’s money was going, particularly in their approval of multiyear fellowships. Thus, Cronin was rewarded for rebuffing St. Antony’s mission as well as Roshan’s.

University of California, Irvine

Matthew P. Canepa |

In 2017 within the School of Humanities an endowment for the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Presidential Chair in Art History and Archaeology of Ancient Iran was established by the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute. Roshan’s emphasis on Persian culture rather than contemporary Iranian politics is highlighted in the expectation that the chair specializes in any or all the three dynasties of the ancient Persian world: Achaemenid, Arsacid, and Sasanian (550 BCE to 650 CE). The new faculty member is housed in UCI’s department of art history and will collaborate with the Samuel M. Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture, UC Irvine’s hub for interdisciplinary research projects that bridge the arts, humanities, engineering, medicine, and the sciences with Persian Studies. The inaugural appointee to the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Presidential Chair in Art History and Archaeology of Ancient Iran was Matthew P. Canepa in July, 2018. His academic background further underscores the significance Roshan puts on Persian culture, as Canepa is an art historian who researches archaeology and religions, with a focus on the intersection of art, ritual, and power in the eastern Mediterranean, Persia, and the wider Iranian world.[31]With Roshan’s financial support, UCI hopes to attract scholars and students from around the world who seek a diverse range of scholarly opportunities in both ancient and modern Iranian and Persian studies. Being housed in the department of art history, the Roshan chair wisely avoids the more controversial association with Global Middle East Studies at UCI whose students are widely active in anti-Zionist groups, such as Student for Justice in Palestine (SJP). In 2016, the Irvine California district attorney announced a criminal investigation of UCI’s SJP chapter, in response to an incident in which protestors interrupted an event by a pro-Israel student organization, chanting “‘Long live the intifada,’ ‘f *** the police,’ ‘displacing people since ’48, there’s nothing here to celebrate’ and ‘all white people need to die.’”

Addendum: In October 2020 Roshan awarded the University of Toronto a $6 million grant to establish the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Institute of Iranian Studies.[32] As of this writing, the Institute is still in the planning stages, including the construction of a new building in which it will be housed. This investment marks a major milestone for Roshan, both in the scope of the grant and in the academic prominence of the recipient. Campus Watch will report on this story as it develops.

Appendix II: Roshan Cultural Institute University Grantees

- Aga Khan University

- University of Arizona

- Brandeis University

- Brown University

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of California, Irvine

- University of California, Los Angeles

- California State University, Fresno

- California State University, Los Angeles

- University of Cambridge

- The University of Chicago

- Columbia University

- Duke University

- École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales

- École Pratique des Hautes Études

- George Washington University

- Georgetown University

- Harvard University

- University of Hawaii at Manoao

- University of Maryland, College Park

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Morgan State University

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- University of North Carolina at Charlotte

- Northeastern University

- University of Oxford

- Pennsylvania State University

- Portland State University

- University of San Diego

- San Jose State University

- Santa Barbara City College

- Stony Brook University

- Syracuse University

- University of Toronto

- University of Virginia

- University of Washington

- Washington University in St. Louis

- Yale University

Appendix III: Roshan Cultural Institute Other Grantees

- Asia Society

- Association for Iranian Studies

- British Library

- Carolina Performing Arts

- Documentary Educational Resource, Inc.

- East-West Center

- The Education and Diversity Foundation

- Hawaii International Film Festival

- Honolulu Chamber Music Series

- Honolulu Museum (Academy) of Art

- International Qajar Studies Association

- Iran Heritage Foundation

- The Iranian Association of Boston

- Iranian Culture and Art Club of Fresno

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Louvre Museum

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema

- The Persian American Society

- Persian Heritage Foundation

- Smithsonian Institution

- St. Andrew’s Episcopal School

- The State Hermitage Museum

- Victoria and Albert Museum

Rebecca Molloy, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and Middle East analyst.

[1] For example, Roshan’s tax returns for 2014 through 2017 show that its largest investments are at universities whose administrations have been more responsive to incitement to violence against Jewish and pro-Israel students on campus (e.g. UMD, see Appendix I). By acting quickly, these schools tamp down problems before they flare up into national news.

[2] Published Date: 03/21/2016 - 4:31pm; accessed 9/28/2018.

[3] U of A has an inactive Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) chapter, and no faculty member has publicly signed the original 2014 BDS letter calling for the academic boycott of Israeli academics. Similarly, Jewish Voice for Peace remains inactive.

[4] Anti-Defamation League’s response to allegations of Israeli “pinkwashing"; accessed 10/4/2018

[5] Her stance against the current Iranian regime is notable in her publications, such as “Islamic Law and the Revolution Against Women,” Worden, Minky (ed.) in The Unfinished Revolution: Voices from the Global Fight for Women’s Rights, Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2012, 53-60; History and Documentation of Human Rights in Iran, trans. Nazila Fathi, New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press, 2000; Refugee Rights in Iran, trans. Banafsheh Keynoush, London: Saqi Books, 2008.

[6] Updated date: 06/26/2018 – 2:08pm; accessed 02/01/2021.

[7] Published date: 11/25/2019 – 11:21am; accessed 02/04/2021.

[8] Published date: 04/19/2019 – 7:00am; accessed 02/04/2021.

[9] Mansoor Moaddel, Kamran Talattof, Contemporary Debates in Islam: An Anthology of Modernist and Fundamentalist Thought, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000; reviewed by Riexinger, Martin. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 36, no. 1 (2002): 65-66.

[10] JSTOR lists the following titles for Betteridge: 1) Betteridge, Anne, and Janice Monk. “Teaching Women’s Studies from an International Perspective,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 18, no. 1/2 (1990): 78-85. 2) Betteridge, Anne H. “Title VI and Foundation Support for Area Studies: Its History and Impacts.” In International and Language Education for a Global Future: Fifty Years of U.S. Title VI and Fulbright-Hays Programs, edited by Wiley David S. and Glew Robert S., 139-54. Michigan State University Press, 2010. 3) Betteridge, Anne H. “Gift Exchange in Iran: The Locus of Self-Identity in Social Interaction.” Anthropological Quarterly 58, no. 4 (1985): 190-202. doi:10.2307/3318149. 4) Betteridge, Anne H. “Ellen-Fairbanks Diggs Bodman 1924 - 2007.” Review of Middle East Studies 45, no. 1 (2011): 152-53. 5) Betteridge, Anne. “James Pitts Alexander.” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 29, no. 2 (1995): 288.

[11] 1) “Muslim Women and Shrines in Shiraz,” In Donna Lee Bowen and Evelyn A. Early, eds. Everyday Life in the Muslim Middle East, 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002. 2) “Shi’ite Festivals,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, Ehsan Yar-Shater, ed. Mazda Publishers, 1998. 3) “Specialists in Miraculous Action: Some Shrines in Shiraz,” in Sacred Journeys: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage, Alan Morinis, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992. 4) “Domestic Observances: Muslim.” In The Encyclopaedia of Religion. Mircea Eliade, ed. New York: Macmillan, 1986.

[12] Leila Hudson, review of Inside Hamas, by Zaki Chehab, in Middle East Journal, vol. 61, no. 4, 2007, pp. 736–738. JSTOR.

[13] Leila Hudson, “The New Ivory Towers: Think Tanks, Strategic Studies And ‘Counterrealism’,” Middle East Policy Council, Volume XII, Number 4, Winter 2005.

[14] See review by Lynne Dahmen, Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Winter 2007), pp. 202-203.

[15] Meftahi publications found: “Sacred or dissident: Islam, embodiment, and subjectivity on post-revolutionary Iranian theatrical stage” in Islam and popular culture eds. Karin van Nieuwkerk, Mark LeVine, Martin Stokes editor. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016.

Gender and Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage, Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis Ltd 2016. This book links the socio-political discourses on performance with the staged public dancer, in order to interrogate the formation of dominant categories of “modern,” “high,” and “artistic,” and the subsequent “othering” of cultural realms that were discursively peripheralized from the “national” stage.

“Dancing angels and princesses: the Invention of an ideal female national dancer in 20th-Century Iran,” in Shay, Anthony and Barbara Sellers-Young, The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Ethnicity, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

“The Sounds and Moves of ibtizal in 20th-Century Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies; Cambridge Vol. 48, Is. 1, (Feb 2016), 151-155.

[16] Intersectionality refers to the cultural construction of one’s identity. It is a sociological term, referring to “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage.” The word has become a rallying cry for people who belong to “various marginalized groups,” urging them to make common cause. It has been used vacuously and viciously to align disparate political causes in the service of radical politics, often against Israel.

[17] Chloé Valdary, “What Farrakhan Shares With the Intersectional Left” Tablet Magazine. March 26, 2018.

[18] Brad Dell, “Faces from Hawaii’s Islam,” Flux, May 26, 2016

[19] Saeid Golkar, “The Rein of Hard-line Students in Iran’s Universities,” Middle East Quarterly; Philadelphia, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Summer 2010), 21-29.

[20] If positive working relationships foster deeper understanding of culture, religion, and history, as Ganjali points out in a 2016 interview, then singling out Israeli artists or academicians by UH’s Ethnic Studies (2013) for boycott must be unacceptable. This position is indeed the official stance adopted by the administration of the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. See letter by Chancellor, Tom Apple: “The administration of the University of Hawai’i at Manoa is in strong opposition to the recent announcement by the American Studies Association of an Academic Boycott of Israel. We have two reasons for this opposition. We respect the right of all individuals to express opposition to the actions of any government, and we understand that many members of the ASA oppose actions of the Israeli government. However, we would assume that this is true of the actions of virtually every government in the entire world, including our own. Israel is the only country, to the best of our knowledge, which has been singled out by the ASA as deserving such a boycott. On what basis, as a result of what investigative process, on the basis of what values, has the ASA come to the conclusion that the actions of Israel are more worthy of condemnation than, say, North Korea, or, to move closer to the region, other US allies such as Saudi Arabia? Surely, a scholarly organization should exemplify scholarly research and inquiry, and we fail to see the ASA living up to this ideal.

The second reason is that no matter what judgment one might want to make concerning the actions of a given government, how can one treat all the citizens of that country as if they represent the actions of that government? It is probably safe to assume most members of the ASA oppose current US practices in Guantanamo Bay. Should ASA boycott itself because it considers those actions objectionable? The implicit notion that we represent our governments regardless of our own beliefs or actions is chilling, indeed Orwellian. The focus of the resolution is on Israeli universities, not individual Israelis, but surely the point is the same: universities should be and are places for open inquiry and a variety of viewpoints, and there is no more unanimity among the members of the Israeli academic community about the actions of their government than there is among the American academic community about our policy in the Middle East.

Surely, our commitment as intellectuals and scholars should be to engage in dialogue with everyone, not to shun the citizens of one nation alone as pariahs. The Executive Committee of the AAU has already argued that this action of the ASA is a violation of academic freedom, not just of Israeli academics but just as clearly of academic freedom in the United States as well, while political activists such as Noam Chomsky have opposed the action of the ASA. We urge the ASA to reconsider this action.”

[21] The amount does not appear on the Roshan site, SJSU site, or on RCHI’s tax returns.

[22] Sarah A. Aghazadeh, “Public Diplomacy for a Global World: The United States and Iran,” M.A. thesis, San Jose State University, May 2015.

[23] See review by Patricia J. Higgins, Iranian Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1, “Iranians in America” (Winter, 1998), pp. 110-112.

[24] Her body of work consists mostly of writings on fundamentalism and religious extremism:

Review of Maleeha Aslam, “Gender Based Explosions: The Nexus between Muslim Masculinities, Jihadist Islamism and Terrorism,” Gender and Society, Vol. 28, No. 2 (April 2014), pp. 319-321.

Review of Maryam Poya, “Women, Work & Islamism: Ideology and Resistance in Iran,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Autumn, 2000), p. 674.

[25] Contemporary Sociology, vol. 41, no. 2, Mar. 2012, pp. 220–221.

[26] Their syncretic religious system (also known as Yarsanism) negates many of Islam’s fundamentals in terms of beliefs, rituals and symbolism. See Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Inner Truth and Outer History: The Two Worlds of the Ahl-i Haqq of Kurdistan,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2 (May, 1994), pp. 267-285.

[27] Review of “Muslim Women in America: The Challenge of Islamic Identity Today by Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad, Jane I. Smith, Kathleen M. Moore,” in Review of Middle East Studies Vol. 46, No. 2 (Winter 2012), pp. 256-258.

“Yusuf’s “Queer” Beauty in Persian Cultural Productions,” The Comparatist, Vol. 40 (October 2016), pp. 245-266. Review of Margot Badran, “Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 43, No. 4 (November 2011), pp. 754-755.

“Mapping Out Socio-Cultural Decadence on the Female Body: Sadeq Chubak’s Gowhar in Sange-e Sabur,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 39, No. 2, Mapping Gendered Violence (2018), pp. 206-232.

“Shifting Sexual Ideology and Women’s Responses: Iran Between 1850 – 2010,” in Homa Hoodfar and Anissa Lucas (eds.), Sexuality in Muslim Contexts: Restrictions and Resistance (2012).

“Socially Peripheral, Symbolically Central: Sima in Behrouz Afkhami’s Showkaran,” in Journal of Asian Cinema (fall 2016).

Subjectivity in ‘Attar, Persian Sufism, and European Mysticism, Purdue University Press, 2017.

[28] Yaghoobi, review of Arta Khakpour, Mohammad Mehid Khorrami, and Shouldeh Vatanabadi. Review of Middle East Studies 51, no. 2 (2017): 298-300.

[29] Op. cit., 299

[30] Yaghoobi, Claudia. Review of Middle East Studies 46, no. 2 (2012): 256-58.

[31] Canepa’s interests are reflected in publications, such as: The Iranian Expanse :Transforming Royal identity Through Architecture, Landscape, And The Built Environment, 550 BCE-642 CE, Oakland, California : University of California Press 2018; “Emperor” in Chin Catherine M. and Vidas Moulie (eds.) Late Ancient Knowing: Explorations in Intellectual History (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015), 155-74; “Technologies of Memory in Early Sasanian Iran: Achaemenid Sites and Sasanian Identity,” American Journal of Archaeology 114, no. 4 (2010): 563-96; The Two Eyes of the Earth. Art and Ritual of Kinship between Rome and Sasanian Iran, Berkeley: UC Press, 2009.

[32] Published date: 10/30/2020 – 9:40pm; accessed 02/01/2021.