|

| Vol. 6 No. 2/3 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page |

February-March 2004 |

|

|

Dossier: Hassan Nasrallah Secretary-General of Hezbollah |

|

Israel's strikingly asymmetrical concession has consolidated Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah's status as one of the most widely revered public figures in the Islamic world today. Newspapers throughout the Middle East praised the 43-year-old Islamic fundamentalist leader as a paragon of courage and steadfastness. Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, hailed the prisoner exchange as proof positive that "the evil Zionist regime can be defeated by the strong will and concrete faith of the fighters of Islam."[1] Ahmed Yassin, spiritual leader of the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas, pledged that his movement will follow in Hezbollah's footsteps by kidnapping more Israelis.

While there have always been militant Arab leaders who incite anti-Israeli violence by preaching hatred, the staunch belief of many Palestinians today that violence can force Israel to make unilateral concessions is largely due to Nasrallah. Israel's May 2000 withdrawal from south Lebanon in the midst of a bloody conflict with Hezbollah - and without even informal assurances of non-hostility from the enemy - is the most resounding "success story" in the history of the Arabs' conflict with Israel. It is no accident that, at Nasrallah's urging, Palestinian terrorist groups launched a holy war of unprecedented lethality against Israel four months later. Nasrallah's latest triumph is likely to embolden Israel's enemies even further.

While his ability to incite (and, increasingly, direct) Palestinian terrorism against Israel has long fueled concern in Washington, Nasrallah poses a much more direct threat to American national interests. Testifying before the Senate Select Intelligence Committee on February 24, CIA Director George Tenet warned that Hezbollah has cultivated an extensive network of operatives on American soil and an "ongoing capability to launch terrorist attacks within the United States." In recent months, moreover, it has infiltrated the Iraqi Shiite community to prepare the groundwork for a terror campaign against American-led coalition forces. Nasrallah is today viewed in American government circles as a greater threat than Osama bin Laden.

Background

Hassan Nasrallah was born in 1960 in the Bourj Hammoud neighborhood of East Beirut, but his family was originally from Bassouriyeh, a village near the city of Tyre in south Lebanon. Although his family was not particularly religious by Lebanese standards, Nasrallah, the eldest of nine children, became obsessed with Islam and began reading fundamentalist literature at an age when most of his peers were playing soccer.

In 1975, the outbreak of civil war in the heart of the Lebanese capital forced his family to return to Bassouriyeh. Nasrallah's move to south Lebanon brought him into contact with the Amal movement of Musa Sadr, a widely revered religious figure who campaigned against the feudalistic Shiite political elite, and he quickly became a member. While attending a public school in Tyre, Nasrallah frequented the city's main mosque and caught the attention of its most influential cleric, Muhammad al-Gharawi. Impressed by the youngster's intelligence and interest in higher theological learning, Gharawi wrote a letter of recommendation on his behalf to Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, one of the leading clerics in the Shiite seminary (hawza) of Najaf in Iraq. The following year, after finishing his secondary education, Nasrallah traveled there to begin his studies.

Upon his arrival in Najaf, Nasrallah met with Baqir, who placed him under the supervision of one of his disciples, Abbas al-Musawi, a Lebanese cleric from the Beqaa Valley. The sixteen-year-old formed a lasting personal bond with his mentor and formulated much of his worldview under his tutelage. Whereas Musa al-Sadr viewed the Lebanese state as a legitimate entity in need of reform and had developed close ties with reform-minded Christian politicians, Musawi and other radical Lebanese seminarians in Najaf refused to accept the state of Lebanon, its current borders, or its consociational power-sharing formula as unassailable facts. Their acknowledged leader was Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah, a mujtahid (authority in religious law) who returned to Lebanon from Najaf in 1966. Spurned by Sadr and the Lebanese Shiite clerical establishment, Fadlallah formed the Lebanese Islamic Da'wa Party and ran an independent network of clinics, schools, and charitable associations.

In 1978, hundreds of radical Lebanese clerics and students, including Musawi and Nasrallah, were forced to leave Iraq. Their return to Lebanon coincided with the mysterious disappearance of Sadr during a visit to Libya, whereupon leadership of Amal passed to Nabih Berri, a secular lawyer with close ties to Syria. Under Berri's leadership, Amal alienated many religious Shiites by supporting the Syrian-backed presidency of Elias Sarkis and compromising Sadr's struggle for social and political reforms. The secularization of Amal provided the Najaf deportees with an ideal setting to spread their militant brand of Shiite activism. After his return, Nasrallah studied and taught at a religious institute established by Musawi in Baalbak; his youth, charisma, and impassioned oratory appealed to many estranged young Shiites and he gained an impressive body of followers.

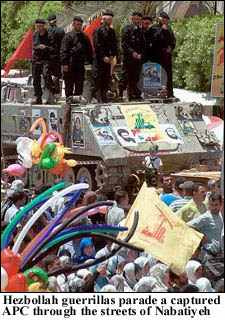

Following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982, Iran sent several hundred Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) officers into the Beqaa Valley of eastern Lebanon to organize a revolutionary movement aimed at waging jihad against Israeli forces and establishing an Islamic republic in Lebanon. Following the lead of Musawi, Nasrallah quickly left Amal, taking many of his followers with him. The new organization was initially an umbrella group composed of militant pro-Iranian clerics and their followers; most of the spectacular suicide operations against Israeli troops and Western peacekeeping forces from 1982 to 1984 were carried out under cover names, such as the "Revolutionary Justice Organization" and the "Organization of the Oppressed on Earth." In 1985, Hezbollah (Party of God) officially announced its existence in an open letter to a Lebanese newspaper and vowed to wage holy war against Israel and its Western supporters.

Nasrallah distinguished himself as a military commander. In 1987, Hezbollah forces under his command succeeded in driving the Amal militia out of several positions in the southwestern suburbs of Beirut. After Syria stepped in and forced the rival militias to stop fighting, Nasrallah traveled to Iran and resumed his theological studies at the seminary of Qom. This was partly an act of protest against Syria's move into Beirut, but it also stemmed from his recognition that proper (i.e. Iranian) religious credentials were as important as military prowess in assuming a greater leadership role within Hezbollah. In 1989, when fighting between Hezbollah and Amal reignited, Nasrallah again interrupted his religious studies and returned to his homeland, where he led Hezbollah forces in a successful drive against Amal in the Iqlim al-Toufah region of south Lebanon and was lightly wounded in battle. By the end of the decade, he had become head of the group's Central Military Command and a member of its politburo.

At that time, Hezbollah's leadership was deeply fractured. One faction, led by Musawi, advocated acceptance of the 1989 Taif Accord, the political blueprint for Lebanon's Second Republic, which meant a de facto abandonment of Hezbollah's declared goal of establishing an Islamic theocracy and acceptance of Syrian hegemony in Lebanon. Musawi's faction, backed by Fadlallah, also mandated the release of Western hostages held by Hezbollah and a narrower focus on combating Israel. A second faction, headed by Nasrallah and Sayyid Ibrahim al-Amin, who had closer relations with the IRGC and direct control of Western hostages, advocated rejection of the Taif Accord and unrelenting hostility toward the United States.[2]

Although influential Iranian clerics, such as Ali Akbar Mohtashemi, backed the second faction, the first was supported by Iranian President Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who strove to project a more moderate image of Iran and shore up ties with Syria after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. As a result of Rafsanjani's success in weakening the hardliners' control over Hezbollah, the first faction emerged victorious at a September 1989 meeting of Hezbollah leaders in Tehran. Nasrallah was subsequently called back to Iran (ostensibly to serve as Hezbollah's representative there) in what appeared to be an effort to sideline him.

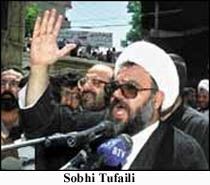

In October 1990, Syrian forces invaded East Beirut and swept away the last remnants of Lebanon's First Republic. While all other major militias disarmed and demobilized over the next year as Syria's puppet regime expanded its writ across the country, Hezbollah was allowed to maintain and expand its military presence in south Lebanon on the condition that all major decisions concerning its war against Israeli forces in the so-called "security zone" be cleared with Damascus. The following year, Tehran agreed to replace Hezbollah Secretary-General Sobhi Tufaili with Musawi, who was closer to Damascus, but won Syrian approval for the return of Nasrallah, who began professing "moderate" political views.

In February 1992, Musawi was ambushed and killed in an Israeli helicopter assault. Although Deputy Secretary-General Naim Qassem was next in the line of succession, Nasrallah was appointed to replace his mentor at the insistence of Ayatollah Khamenei.

Confronting Israel

The first order of business for Hezbollah after Nasrallah's ascension was retribution for the assassination of Musawi. On March 17, a car bomb hit the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, killing 29 people, in an attack that Argentine investigators later concluded was carried out by Hezbollah.[3] While the planning for this unprecedented projection of Hezbollah power overseas had preceded Musawi's assassination for at least a year, its timing was intended to communicate to Israel that killing senior Hezbollah officials would result in the murder of Jews overseas. The embassy bombing was the first installment in a broader strategy of using terror attacks on Israeli and Jewish civilians to deter Israel from forceful action in Lebanon. It worked. Although Israeli intelligence planned and trained operatives for an assassination of Nasrallah, the order was never given. In the years that followed, Nasrallah appeared regularly in public, often speaking before crowds numbering in the tens of thousands, without fear of assassination.

Hezbollah operations became progressively more sophisticated and deadly after Nasrallah's ascension (26 Israeli soldiers died in combat in south Lebanon in 1993, double the number for 1992). This was partly due to his own managerial skills and innovative military ideas, but also reflected the fact that the Iranians gave Nasrallah a much broader leadership mandate than his predecessors - he was allowed to appoint military commanders on the basis of competence, with less regard for their affiliations with this or that cleric. However, while major advances were made in Hezbollah's combat strength, its success on the battlefield remained integrally tied to its ability to strike Israeli and Jewish targets off the battlefield.

For example, Hezbollah's combat effectiveness against Israeli and South Lebanon Army (SLA) forces depended greatly on its use of villages near the security zone to shelter guerrillas - Hezbollah units typically retreated into civilian settlements after launching attacks. This tactic was viable only if Israel could be deterred from carrying out reprisals against attack squads when they fled into civilian areas. Although Hezbollah's Katyusha rocket attacks into northern Israel during the 1990s were commonly portrayed in the Israeli media as random acts of terror, they frequently came in response to Israeli reprisals in Lebanon. During Israel's seven-day air and artillery offensive against Hezbollah in July 1993 (Operation Accountability), 142 Katyushas hit Israeli territory. Afterwards, Israel reached an informal understanding with Hezbollah to refrain from reprisals into civilian inhabited areas of Lebanon in exchange for a halt to attacks against Israel proper.

The July 1993 understanding (formalized after the April 1996 conflagration) not only limited Israel's ability to strike at Hezbollah forces arrayed against it in south Lebanon, but caused friction between Israel and its Lebanese militia allies because it did not restrict Hezbollah's freedom to launch Katyushas against population centers in the security zone. As a result, one Israeli commentator noted, "morale in the SLA plummeted. A wave of defections began and the SLA threatened to collapse."[4] Crumbling SLA morale translated into an intelligence bonanza for Hezbollah and, as a result, its operations became steadily more sophisticated in the mid-1990s. When the 1993 understanding broke down for sixteen days in April 1996, Hezbollah launched 489 Katyusha rockets across the border before it was reinstated and formalized in writing.

In May 1994, helicopter-borne Israeli commandos penetrated deep into the Beqaa Valley of eastern Lebanon and captured Mustafa Dirani, the leader of a pro-Hezbollah Islamist offshoot of Amal. Although Dirani was not a member of Hezbollah, Nasrallah was deeply unsettled by this stunning projection of Israeli power and publicly resolved to match it with a projection of Hezbollah's power.[5] On July 18, a suicide bomber drove a van carrying 600 lbs of explosives into the Argentine-Israeli Mutual Association (AMIA) building in Buenos Aires, killing 85 people. Although Nasrallah strenuously denied Hezbollah's involvement in the blast, a lengthy investigation by Argentina's intelligence services eventually concluded that Hezbollah and Iranian officials had planned and financed the bombing.[6] Much like the embassy attack two years earlier, the bombing of the AMIA building was a strategic success - Israel subsequently refrained from kidnapping high profile militants in Lebanon. Argentine President Eduardo Duhalde later said that Hezbollah had planned to carry out a third attack in 1996 against Israeli or Jewish targets in the country, but was thwarted by the security services.[7]

|

Hezbollah's military achievements would not have been possible without Iranian and Syrian sponsorship. Hezbollah's overseas terror network, a decisive factor in skewing the rules of the game in south Lebanon, was intricately linked to Iranian intelligence (its head of special overseas operations, Imad Mughniyah, is believed to reside in Tehran). Hezbollah training facilities and supply depots in the Beqaa Valley were protected by dense layers of Syrian anti-aircraft defenses.

However, while Nasrallah cannot claim full credit for Hezbollah's performance on the battlefield, he was largely responsible for its sophisticated use of psychological warfare to prod Israeli public opinion, which typically is not "softened" by casualties alone (the hardening of sentiments amid unprecedented civilian deaths during the current Palestinian intifadah is a testament to this). Hezbollah propagandists learned Hebrew so as to keep abreast of the debate within Israel and identify "soft spots" in public support for the Israeli presence in south Lebanon. Nasrallah was careful to maintain publicly that Hezbollah's war against Israel will end once the Israeli military leaves south Lebanon. In 1996, Hezbollah's Al-Manar television station (and Al-Nur radio station) began Hebrew language broadcasts centered on this message.

By the end of the decade, Israeli public opinion had shifted in favor of a pullout. In May 1999, Ehud Barak was elected prime minister on a platform calling for the evacuation of Israeli forces from Lebanon, with or without a peace treaty with Syria and Lebanon. Although Barak honored his pledge and Israeli forces pulled out a year later, Hezbollah's war against Israel had only just begun.

The Domestic Front

Although the Israeli pullout earned Nasrallah rapturous acclaim throughout the Arab world, his most striking accomplishment during the 1990s was the transformation of Hezbollah from a secretive revolutionary group despised by most non-Shiites into a major social and political force in Lebanon.

In 1992, Hezbollah was still the odd man out in Lebanese politics. Although Hezbollah had dropped its calls for the establishment of an Iranian-style theocracy and endorsed the Second Republic, the movement was viewed with disdain by most non-Shiite politicians. Even within the Shiite community, Hezbollah faced competition from the secular Amal movement, which enjoyed strong Syrian backing. Berri was appointed speaker of the house - the highest Shiite political office in Lebanon - and given control over the Council of the South, a government agency responsible for allocating development funds in south Lebanon.

Moreover, at the time of his ascension, Nasrallah was the odd man out in Hezbollah politics. Unlike his two predecessors and the majority of the movement's military commanders, Nasrallah hailed from south Lebanon, not the Beqaa. He was not from a distinguished clerical family and there was considerable grumbling about his lack of religious credentials - Tufaili and Musawi had spent eight and nine years, respectively, studying theology in Najaf, while Nasrallah had been there for only two. His age - 31 at the time of his ascension - placed him a full generation behind many prominent Shiite clerics in Lebanon. Moreover, Nasrallah had reversed himself on many key issues in recent years, behavior decried by some of his peers as indicative of either youthful impressionability or political opportunism. While Nasrallah had Khamenei's blessing, others in Hezbollah had closer ties to Iranian clerics actually in charge of the "Lebanon file" and impressive bodies of followers in Lebanon.

The first major political decision faced by Nasrallah was whether Hezbollah should participate in the August-September 1992 parliamentary elections. A number of senior Hezbollah figures had loudly expressed their opposition to fielding candidates for the elections. Some, such as Tufaili (who famously threatened to burn voting booths in his hometown of Britel) did so out of principle, while others argued that Hezbollah's participation in a political system viewed by most Lebanese as illegitimate was foolish from a public relations standpoint unless the movement was allowed to exercise commensurate influence in the government. But it was clear from the very beginning that Hezbollah would not be permitted by the Syrians to challenge Amal's postwar political inheritance. Even if this were allowed, under the current constitution Hezbollah would still be unable to assume control over the executive branch through majority vote.

Ultimately, Nasrallah had little choice in the matter, as both the Syrians and the Iranians were pressing Hezbollah to participate. The outcome of the elections in the south and Beqaa was predetermined by a Syrian-mediated pre-election agreement between Hezbollah and Amal that prevented their candidates from directly opposing each other. The party won eight seats in the 128-member assembly, and non-Shiite candidates running on Hezbollah electoral lists won four seats.

However, Hezbollah refused to be represented in the cabinet. Nasrallah later explained that accepting cabinet portfolios would have caused the party to "bear responsibility for mistakes" that were not its own.[8] Representation in parliament gave the party a powerful pulpit, while exclusion from government allowed it to freely critique the authorities. While soft-pedaling narrowly Islamist causes, Nasrallah endlessly lambasted the government of Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri on issues such as political corruption, administrative inefficiency, and the low level of government funds allocated to development projects in poor areas of Lebanon. Hezbollah MPs raised two votes of no confidence against the government during the 1990s. Interestingly, Nasrallah's domestic political agenda led many of the movement's activists to coordinate at the grassroots level with members of the anti-Syrian Free National Current (FNC) in opposing corruption and political patronage.[9]

Hezbollah poured enormous sums of money into building and consolidating an extensive social welfare network in Shiite regions, including schools, clinics, subsidized housing in the southern suburbs of Beirut. While Iranian aid constituted the bulk of Hezbollah's finances for such projects at the time of his ascension, Nasrallah cultivated an elaborate network of financing from expatriate Lebanese Shiites around the world. Small-scale donors tended to be moved by mass-produced Hezbollah propaganda videos and cassettes that flooded their mosques, but the largest contributors often succumbed to extortion - wealthy Lebanese expatriates who failed to make "charitable" contributions to Hezbollah have reported being threatened with reprisals against their relatives in Lebanon.

The Shiite Lebanese Diaspora also provided Hezbollah with a base for lucrative criminal activities, such as diamond smuggling in West Africa, cigarette smuggling in the United States, and drug trafficking in the triple frontier along the junction of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. By the end of the 1990s, funding from the Lebanese Diaspora had outstripped Iranian financing, estimated by Lebanese press reports to be around $10 million monthly.

Nasrallah had the foresight to recognize that Amal was too corrupt to convert its privileged political status into grassroots support within the Shiite community. Whereas Hezbolllah used its financial resources to build grassroots support among the lower classes, Berri used state resources under his control to enrich his cronies and political allies. The relatively small portion of government funds allocated to the Council of the South and other Amal-controlled government agencies that was not diverted for illicit use found its way mainly to pro-Amal districts in the south.[10] While such blatant use of government funds as political patronage bolstered support for Amal in specific geographic areas, it steadily eroded Berri's stature within the Shiite community as a whole.

While Nasrallah cannot claim full credit for Hezbollah's stunning military successes in south Lebanon, he was largely responsible for Hezbollah's adept marketing of war with Israel within both the Shiite community, which bore the brunt of Israeli reprisals, and Lebanon as a whole, which suffered indirectly from its impact on foreign investment. The September 1997 death in combat of Nasrallah's eighteen-year-old son, Hadi, was a public relations bonanza in a country where the sons of politicians typically avoid the draft.

Nasrallah's drive to establish Hezbollah's political supremacy within the Shiite community and its campaign against government corruption - the lifeblood of Syrian control over Lebanon's political class - put the movement at odds with Damascus. When the Syrians refused to sanction an increase in Hezbollah's parliamentary representation prior to the 1996 elections, Nasrallah refused to form a joint electoral slate with Amal and paid a heavy price. After Hezbollah candidates fared miserably in the first two rounds of the elections in Beirut and Mount Lebanon, Nasrallah reluctantly accepted a joint slate prior to the elections in south Lebanon, but Hezbollah's representation still declined from "eight plus four" to "seven plus three."

|

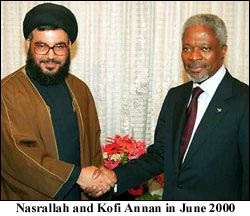

Hezbollah in Transition

Israel's unilateral withdrawal from south Lebanon catapulted Nasrallah into the spotlight throughout the Arab world as the only man to have defeated the Jewish state on the battlefield. However, defying expectations that Hezbollah would turn inward and concentrate on domestic political concerns, Nasrallah saw the Israeli pullout as an opportunity to position Hezbollah as a regional political player. The death in June 2000 of Syrian President Hafez Assad, who personally disliked Islamic fundamentalists and viewed Hezbollah with suspicion because of its Iranian loyalties, facilitated such a transition. Whereas his late father kept Nasrallah at arms length, often forcing him to sit in a waiting room for hours during his infrequent trips to Damascus, Bashar Assad fawned over Nasrallah during his visits to the Syrian capital. While Bashar's warm relationship with Hezbollah was partly due to his personal admiration for Nasrallah, it was also politically astute, as the young dictator was anxious to upgrade ties with Iran and bolster his anti-Israeli credentials.

|

In return for increased support from Damascus, Nasrallah offered Syria unprecedented political support at a time when opposition in Lebanon to its military presence was on the rise. Until Bashar's ascension, Hezbollah officials had avoided explicit expressions of support for the Syrian presence in Lebanon. This changed after Maronite Christian Patriarch Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir returned from a trip abroad to rally diplomatic support for a Syrian pullout in March 2001 and received a tumultuous reception from tens of thousands of supporters. Damascus decided that an even larger counter-demonstration in favor of the Syrian presence was in order and Hezbollah was the only political group in Lebanon capable of organizing it. On April 4, Nasrallah addressed a crowd of roughly 300,000 Hezbollah supporters and declared the presence of Syrian forces in Lebanon to be "a regional and internal necessity for Lebanon" and a "national obligation for Syria."

After the outbreak of the Palestinian intifadah in September 2000, Hezbollah was allowed to launch sporadic cross-border attacks in the Israeli-occupied Shebaa Farms area of the Golan Heights (an area it spuriously claims is Lebanese), while Syria prohibited the Lebanese army from deploying to the border zone. In October, Hezbollah guerrillas killed and made off with the bodies of three Israeli soldiers and kidnapped Elhanan Tennenbaum, a reserve air force colonel lured by Hezbollah operatives into traveling abroad. Although negotiations between Hezbollah and Israel through German intermediaries commenced shortly after the abductions, they stalled after Nasrallah insisted that all Arab prisoners be released by Israel.

Meanwhile, Al-Manar began transmitting by satellite, increased its daily broadcast hours, and focused more of its programming on anti-Israeli incitement - today, it is watched by an estimated 10 million people. Hezbollah greatly increased its training of operatives from Palestinian terrorist groups, such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Hezbollah was involved in at least three major attempts to smuggle weapons to the Palestinians.[11] Lebanese drug dealers experienced in smuggling contraband into northern Israel were commissioned by Hezbollah to recruit a network of Israeli Arab spies, who provided the group with valuable intelligence about prospective targets for terrorist attacks. By mid-2001, Hezbollah had begun recruiting its own network of Palestinian operatives in the West Bank, enabling Nasrallah to directly commission terrorist attacks against Israelis. In recent months, Hezbollah terror cells have been uncovered in Gaza and in the Israeli Arab community.

Hezbollah's performance won widespread praise among hard-liners in Tehran and bolstered their efforts to lobby for quantitative and qualitative upgrades to the group's military apparatus. Hezbollah's rocket arsenal was tripled in size and augmented by hundreds of long-range rockets capable of striking targets deep in the civilian and industrial heartland of Israel. Construction crews worked around the clock converting caves into underground bunkers to house the weapons. There have also been unconfirmed reports that Hezbollah has acquired sophisticated SA-18 shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles.

Whereas Hezbollah's pre-2000 "war of liberation" drew considerable public support in Lebanon, its continued war with Israel has received mixed reviews at home. The country's post-war entrepreneurial class, while beholden to Syria, is anxious to exploit economic opportunities, especially construction and tourism projects, that would open up in south Lebanon once security is established there. More importantly, foreign investment in the country as a whole is unlikely to rise substantially so long as Lebanon remains an active theatre of the Arab-Israeli conflict. It was for this reason that Hariri openly objected to Hezbollah's resumption of cross-border attacks in early 2001 (he was later silenced by Syrian pressure). Even within the Shiite community, Hezbollah has found that confronting Israel is no longer a cause that brooks unanimous approval. Leftist politicians, such as former MP Habib Sadek, and scions of the Shiite community's traditional political elite, such as Ahmed Asaad, have expressed guarded criticism of Hezbollah provocations.

Nasrallah and the US War on Terror

Hezbollah was initially excluded from the US "war on terror" in the aftermath of 9/11. Concerned that violence in south Lebanon would disrupt American efforts to secure Arab support for the war in Afghanistan, the Bush administration assured Damascus that it would not explicitly target Hezbollah as long as it refrained from violent provocations against Israel. However, after Hezbollah broke a three month lull along the border with two attacks in October, President Bush called the movement a terrorist group of "global reach" and, the following month, added Hezbollah (along with several Palestinian groups) to its "priority list" of terrorist organizations, threatening sanctions against foreign banks that decline to freeze their assets. National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice went so far as to warn that Lebanon's refusal to cooperate could jeopardize its "integration into the world economy" and even threaten its economic "survival." Rumors circulated in Beirut that the Bush administration was canceling all US aid to Lebanon and working to "torpedo" the upcoming Paris-II donor conference, a vital source of handouts for Lebanon's debt-stricken government.

Neither happened, as the Bush administration soon turned its attention to Iraq and focused on winning Syrian support for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but diplomatic efforts were made to isolate Hezbollah internationally and administration hawks continued to berate Hezbollah, as if to warn Assad of the direction American policy might take if he remained uncooperative. In a September 2002 speech at the US Institute of Peace, Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage called Hezbollah the "A-team" of terrorists, with a "blood debt" to the United States (a reference to the US embassy and marine barracks bombings in Beirut in the early 1980s, which left hundreds of Americans dead), and vowed that its "time will come." Neoconservative media outlets in the United States portrayed Hezbollah as the next al-Qaeda. Under pressure from the United States, Canada officially designated Hezbollah a terrorist organization in late 2002, followed by Australia in mid-2003. Although the European Union declined to follow suit, new constraints on Hezbollah's ability to raise funds among the large Lebanese expatriate communities in Canada and Australia have begun to have a modest impact on the group's finances.

As a result of Assad's refusal to halt military assistance to Saddam Hussein's army before the war and covert support for anti-American insurgents after the war, US-Syrian relations hit a 20-year nadir in 2003. However, the Bush administration has been slow to resume its tough talk on Hezbollah. There is a feeling among Washington insiders that the issue has been deferred until after the American presidential election, but a more substantial consideration is also at work - the prospect of Nasrallah inciting a Shiite uprising against American forces in Iraq.

Scores of Hezbollah militants have been sent to Iraq over the last ten months and the group has reportedly opened offices in Basra and Safwan. The Hezbollah office in Safwan was "secure with guards and weapons," said Zainab Al-Suwaij, executive director of the American Islamic Conference, after returning from a visit to southern Iraq in January.[12] According to American intelligence reports, Hezbollah operatives have focused mainly on establishing lines of communication with Iraqi Shiite leaders and distributing anti-American propaganda, but the groundwork is clearly being laid for incitement of violence in the future.

Notes

[1] "Iran, Arabs sing Hezbollah's praises following prisoner swap," Agence France Presse, 30 January 2004.

[2] Hezbollah Secretary-General Sobhi Tufaili's stance was ambiguous - he sympathized with the hard-liners, but outwardly supported the first faction, because his hometown in the Beqaa was under Syrian occupation.

[3] In September 1999, Argentina issued an international arrest warrant for Imad Mughniyah, Hezbollah's head of overseas operations, in connection with the bombing.

[4]

Naomi Levitzky, The IDF vs. Hizbullah: The Unfinished Battle, Yediot Ahronot, 8 July 1994. Translation by Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[5] "Not only Israel has a long arm . . . there exist several long arms which could react to Israel's activity," his chief political advisor, Hussein Khalil, warned after the kidnapping (Reuters, 21 May 1994). Weeks later, Nasrallah explicitly warned that "a thousand suicide commandos are ready to strike Israel all over the world" (Al-Watan Al-Arabi, 17 June 1994).

[6] Clarin (Buenos Aires), 19 January 2003. Argentine Federal Judge Juan Jose Galeano later issued arrest warrants for eight former Iranian diplomats for their involvement in the bombing, but no Hezbollah officials were formally charged - evidently due to political considerations (there are many Lebanese Shiite immigrants in Argentina, but few Iranians).

[7] La Nacion (Buenos Aires), 23 February 2000.

[8] Al-Hawadith, 19 March 1999. Cited in Amal Saad-Ghorayeb, Hizbu'llah: Politics and Religion (London: Pluto Press, 2002), p. 32.

[9] For instance, when the Lebanese doctors' association held elections in March 2001 for a new chairman, Hezbollah and the FNC joined together in backing the losing candidate, Dr. Saad Bizri, over Dr. Mahmoud Shuqair, who enjoyed the firm backing of such political heavyweights as Hariri and Berri.

[10] For example, in the aftermath of Israel's 1993 Operation Accountability, south Lebanese villages considered sympathetic to Hezbollah did not receive any government aid.

[11] In January 2001, Israel intercepted a ship carrying a large load of weapons, the San Torini, which had departed from Lebanon. A year later, Israel intercepted the Karine A, which embarked from Iran with a Hezbollah-trained crew. In May 2003, Israel seized an Egyptian fishing boat, the Abu Hassan, attempting to deliver explosives from Lebanon to Gaza; a Hezbollah explosives expert, Hamad Masalem Mussa Abu Amra, was on board.

[12] �Iraqi: Hamas, Hezbollah operating in Iraq,� United Press International, 15 January 2004.

� 2004 Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. All rights reserved.