|

| Vol. 3 No. 11 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | November 2001 |

| | Dossier: Emile Lahoud President of Lebanon |

|

Lahoud's seemingly paramount authority is largely a veneer, however - it is his Syrian patrons who reign supreme over the political process in Lebanon. The country's military-security apparatus, staffed by loyal Syrian allies, takes its orders from Damascus, not Lahoud. The will of parliament was bent not by the president of Lebanon, who has little political support, particularly within his own Maronite Christian community, but by the president of Syria.

Nevertheless, this figurehead at the helm of Lebanon's Second Republic is a critical nexus in Syria's efforts to legitimize its hegemony over the country. His ascension three years ago was designed to rally support from the disaffected Christian community, which has lacked a credible representative in the power structure since Syria completed its conquest of Lebanon in October 1990. The appointment of Lahoud, and his empowerment vis-à-vis the Sunni Muslim prime minister and Shi'ite Muslim speaker of parliament, was intended to fill this leadership vacuum by offering the Christians a powerful political leader who would protect Christian political interests and cultural autonomy in return for abandoning opposition to the Syrian occupation. This initiative, it was thought, would deal a death blow to the Lebanese nationalist movement by weakening its center of gravity in the Christian community.

However, Lahoud's tenure as president of Lebanon has not witnessed the decline of the nationalist movement challenging Syrian authority, but its growth and expansion across the ideological and sectarian spectrum. Syrian efforts to seal a partnership between Lahoud and the Christian religious establishment have thus far proved fruitless, while the traditional Christian political elite have remained reluctant to openly endorse Lahoud as their leader. The empowerment of Lahoud and the military-security complex in Lebanon has so alienated the population that some of the Syrian regimes closest allies, such as Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, have begun calling for an end to Syrian control over the country.

Background

Lahoud was born on January 10, 1936 in Baabdat, a town in north Metn. His father, Gen. Jamil Lahoud, was a prominent officer in the Lebanese army who later served as minister of labor and social affairs in 1960 and was a member of parliament from 1960-1964. His mother, Adrene Bajakian, was of Armenian descent.

Lahoud received his elementary education at the La Sagesse school in Beirut and his secondary education at Brumana High School in north Metn. Choosing to follow in his father's footsteps, he entered the military academy in 1956. After graduating as a lieutenant in 1959, he served as a navy engineer and commander of the landing ship Tyre. He then served as commander of the 2nd Fleet from 1966-1968 and the 1st Fleet from 1968-1970. Lahoud also spent a considerable amount of time training overseas. He studied maritime engineering and rescue operations in Britain during the 1960s and received military training at the US Naval Command College in Rhode Island from 1972-73 and 1979-1980.

Although he was trained as a naval officer, Lahoud took advantage of the appointment of his maternal cousin, Gen. Jean Njeim, as army commander and in 1970 was appointed to head the transportation section of the army's fourth division. Although Njeim died in a helicopter crash the following year, Lahoud remained in the army and steadily rose through the ranks of its officer corp. In 1980, he was appointed Director of Personnel in the Army Command. Three years later he was appointed to an administrative position at the defense ministry in charge of coordination between ministry officials and the Lebanese army commander, a position assumed by Gen. Michel Aoun the following year.

|

While the Syrians backed a rival regime operating out of west Beirut, Lahoud initially remained loyal to Aoun. According to a reliable Lebanese military source, Lahoud sought to persuade Aoun to cut a deal with the Syrians to engineer his election as president. However, Aoun steadfastly refused to compromise with Damascus and its militia allies. In the spring of 1989, Aoun attempted to enforce a maritime blockade of illegal ports established various by Syrian-allied militias. In retaliation, Syrian forces shelled civilian areas of east Beirut. This prompted Aoun to declare a "war of liberation" and order the 15,000 Lebanese soldiers under his command into action against the Syrians.

Most military officers under Aoun's command were fiercely loyal to their leader during the bloody fighting that continued intermittently for the next six months. Lahoud, however, earned a reputation for cowardice and dereliction of duty that severely alienated his fellow officers. According to one officer who knew him well, any time a shell would land in the vicinity of his office, Lahoud would scramble into a bomb shelter in the basement. During much of the heaviest fighting, Lahoud left the complex entirely and stayed in the basement of the Al-Manar Hotel in Jounieh. "He became the security barometer for many shop owners in Jounieh," the officer told MEIB. "Every time Lahoud used to come to Al-Manar Hotel, the shop owners and other Jounieh residents would realize that things were not normal and that fighting would start soon. Shops would close down and people used to evacuate the streets." Whereas many Lebanese officers abandoned their personal lives during the war of liberation in the service of their country, Lahoud abandoned his professional responsibilities and spent his time philandering, playing poker, and swimming. In September, after an Arab League-brokered cease-fire took effect, Aoun finally fired him and Lahoud crossed over into Syrian-occupied west Beirut several weeks later.

Meanwhile, the Syrians were looking for a Maronite military officer to assume the position of army commander for the pro-Syrian regime in west Beirut, which was endorsed by the 1989 Ta'if Accords. Scores of Maronite army officers were offered the job, but they all turned the job down. Finally, Lahoud was offered the position. According to one source, Lahoud had connections to an influential Syria army officer, Ali Hammoud, who recommended him for the job. He quickly accepted.

During the next year, Lahoud repeatedly called upon Lebanese army units around the country to rally to his side, but most either remained loyal to Aoun or steadfastly refused to take up arms against him. In October 1990, Syrian forces invaded the capital and routed Aoun's forces, paving the way for the new regime to extend its control throughout the country. According to Lebanese army sources, Lahoud was not permitted by the Syrians to even enter the Defense Ministry for three days following the invasion, as Syrian troops looted the complex and carried off Lebanese military intelligence files.

Lahoud as Army Commander

Lahoud inherited leadership of an army that had been thoroughly emasculated by fifteen years of civil war and a full-scale Syrian invasion. The army's best-equipped and best-trained units, which had remained loyal to Aoun's government until the very end, were decimated and dozens of their officers carted off to prison in Syria. Other units scattered around the country had become mere appendages to various militia forces, in part because they had been organized along sectarian lines.

During his nine-year tenure as army commander, Lahoud presided over a dramatic transformation in the Lebanese military. In 1993, the army instituted "flag service," requiring all Lebanese males to give a full year of military service, resulting in a massive expansion of the military from around 20,000 personnel to 65,000 personnel. Moreover, it was re-equipped with arms donated or sold at bargain prices by the United States, including at least 16 Huey helicopters, 850 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 jeeps and trucks, 60 ambulances, as well as thousands of uniforms, small arms and other equipment. "The Lebanese look like a little American division in their equipment and uniforms," one American officer told The Washington Post in 1998.1 Moreover, Lahoud ensured that all military units were thoroughly integrated across sectarian and regional lines and were frequently rotated around the country.

However, Lahoud's ostensible commitment to stamping out sectarianism in the Lebanese army masked a much more critical function of his role as the first military commander of Lebanon's Second Republic: the Syrianization of the Lebanese army. The 1991 Defense and Security Pact signed by Damascus and its new satellite state required Lebanon "to exchange information related to all security and strategic matters" with the Syrians and to "exchange officers . . . including military instructors . . . to achieve the highest level of military coordination" between the two countries. This meant that Syrian military officers would now be permitted to attend high-level military staff meetings and examine the files of Lebanon's intelligence agencies. Whereas previously most high-ranking military officers received training in Western countries, more officers were now being sent to Syrian military academies.

In practice, the Defense and Security Pact also gave the Syrians full control over decisions by the Lebanese government pertaining to security. In July 1993, for example, Lebanese officials made the mistake of announcing without prior Syrian approval that the Lebanese army would deploy near the Israeli-occupied security zone. Syria quickly overruled this decision and no deployment was undertaken. To this day, Syria refuses to permit the deployment of Lebanese army units along the border with Israel.

The revitalized Lebanese army played a key role in silencing public animosity toward the Syrian occupation and the growing inequity that resulted from the reconstruction policies of Rafiq Hariri, who began his first term as prime minister in 1992. In 1994, the army eliminated the last remnants of Samir Geagea's Lebanese Forces movement and arrested its top leaders. The government subsequently banned public demonstrations and relied upon the military to enforce the decree. Labor disturbances in 1995 and 1996 were quickly suppressed by the deployment of army units in Beirut.

Nevertheless, the Syrians kept a watchful eye over Lahoud through their close allies, such as Brig. Gen. Jamil al-Sayyid, then the deputy chief of military intelligence. On one occasion, Sayyid informed Damascus that Lahoud had met covertly with American intelligence officials on board a US naval vessel in the Mediterranean, prompting the Syrians to investigate the matter.

Lahoud as President

In 1998, Hafez Assad's son and heir apparent, Bashar, took control of the "Lebanon file" from Syrian Vice-president Abdul Halim Khaddam as part of his political apprenticeship. In order to weaken potential threats to his ascension among Syria's "old guard," Bashar sought to weaken Khaddam's key allies in Lebanon, namely Prime Minister Hariri and Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who was Minister of the Displaced in Hariri's cabinet. Both also had close ties to former Syrian military chief-of-staff Hikmat Shihabi, who had been ousted by Bashar earlier that year.

Previously, the Syrians had granted Hariri the position of "first among equals" vis-à-vis President Hrawi (and, to a lesser extent, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri). Fearing that Khaddam and Shihabi would use their ties to Hariri to subvert his authority in the future, Bashar decided to replace Hrawi, whose term was coming to an end, with a new president, backed directly by Bashar's allies in the Syrian military-security apparatus, who could rein in Hariri while attracting support from the country's disaffected Christian community. Lahoud, who was also favored by the Americans, fit the bill.

The issue was undecided until Hrawi traveled to Damascus and met with the Syrians on October 5. Afterwards, Hrawi announced that Lahoud was to be his successor. In order to pave the way for Lahoud's ascension to the presidency, the Syrians pressured the Lebanese parliament to pass a resolution amending Article 49 of the Constitution, which bars high-ranking military officers from running for president within two years of leaving their posts. On October 15, 1998, parliament convened and all 118 deputies present voted to elect Lahoud president. On November 24, Lahoud was sworn in.

Lahoud's election was, not surprisingly, denounced by Aoun, as well as Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who condemned the ascension of a military officer to the presidency and boycotted the parliamentary vote along with nine other deputies. When it became clear that Hariri would have little say in the selection of ministers in the new cabinet, the billionaire tycoon refused to continue as prime minister (a reaction that was apparently anticipated by the Syrians) and Selim al-Hoss was appointed to replace him.

However, Lahoud's election elicited expressions of support and guarded optimism from most Lebanese public figures, particularly in the Christian community, which was strongly opposed to another extension of Hrawi's term. The Council of Maronite Bishops, headed by Cardinal Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir, praised Lahoud's election as president, while expressing reservations about "the way the choice was made." The Beirut Stock Exchange rose sharply as business leaders hoped that the no-nonsense general would rein in the rampant corruption that was sapping the economy.

|

Initially, Lahoud earned considerable public support for launching a "war on corruption" that prosecuted several cabinet ministers and appointees from the Hariri administration on charges of embezzlement, misuse of power, and bribery. However, the investigations were called off by the Syrians after it became clear that the anti-corruption drive risked exposing illegal activities by Hariri's Syrian allies, most notably Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon. Realizing that his public support would evaporate without the anti-corruption drive, Lahoud is said to have begged Assad to fire Kanaan and replace him with his brother-in-law, Maj. Gen. Assef Shawkat. Assad refused, however, apparently fearing that this might lead Kanaan to join forces with other disaffected Syrian officers and stage a coup.

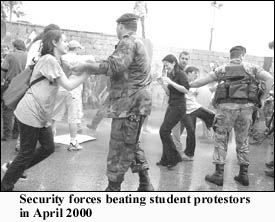

Public support for Lahoud had already begun to dwindle as a result of the new regime's heavy-handed oppression of dissidents. In March 1999, security forces stormed Lebanese university campuses and arrested dozens of demonstrators protesting the Syrian occupation. Three months later, violent clashes erupted between security forces and residents of Jnah in the southern suburbs of Beirut when government officials entered the area to demolish illegal housing units. Even a Greenpeace demonstration in October was deemed to be too unruly, so Lebanese soldiers beat the protestors with rifle butts.

|

Lahoud had made the mistake of alienating Hariri and Jumblatt without finishing them off politically. Taking advantage of widespread anti-government dissent, the two combined forces to sweep the 2000 parliamentary elections in most districts and return Hariri to the premiership.

After the elections, open criticism of the Syrian presence spread across the ideological and confessional spectrum. In September, the Council of Maronite Bishops released a statement calling for a Syrian withdrawal and a dissident faction of the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) demanded a "reappraisal" of ties with Syria. Jumblatt and a host of other Muslim leaders, such as Sunni MP Mustapha Saad and Shi'ite politician Kamil al-Asa'ad, a former speaker of parliament, began openly calling for an end to Syrian hegemony. Lahoud reacted to the growing wave of dissent by accusing critics of the Syrian presence of enflaming sectarian divisions and conspiring to serve Israeli interests.

Within the Christian community, support for Lahoud, who went so far as to accuse the Maronite bishops of "encouraging sectarian bigotry,"2 dropped to an all-time low. Many Christians were originally supportive of Lahoud's presidency because they believed that anyone who had spent his career the army - long considered the heart and soul of Lebanese nationalism - would rise to the occasion and assert Lebanese sovereignty. In fact, Lahoud demonstrated even less autonomy vis-à-vis the Syrians than did his predecessor (few thought this was even possible until Lahoud proved otherwise).

One of the most humiliating illustrations of Lahoud's deference to Damascus came during the October 2000 Arab summit meeting in Cairo, as the various Arab heads of state in attendance rose to speak before the body. Lahoud had planned, like his counterparts, to deliver a lengthy diatribe against the Israelis. He had given the speech to Bashar Assad for final approval, but the Syrian leader had not finished reading it when Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak suddenly called upon Lahoud give his address. Rather than risk upsetting the Syrians by delivering the prepared text, Lahoud rose and stumbled through an ad hoc speech that lasted barely a minute.3

Lahoud's deference to Syria was seen by most Lebanese as having an extremely detrimental impact upon the country's international standing. In December 1999, when Israel and Syria resumed peace talks in the US, American President Bill Clinton called several Arab heads of state to update them on the progress, but didn't bother to phone Lahoud, despite the centrality of south Lebanon in the discussions. Lahoud went ballistic and a diplomatic official close to him complained to reporters about American "negligence," adding that Lebanon is "a major party in the peace process."4

In March 2000, shortly after Israel announced its intention to withdraw from south Lebanon, Lahoud suddenly declared that Palestinian guerrillas in Lebanon would resume attacks against Israel if it pulled out before the negotiation of a comprehensive peace settlement, a statement which mortified most Lebanese (who, if they agree upon anything, contend that the Palestinians should never again be permitted to fight Israel from Lebanese soil).

Due to the steady decline of public confidence in Lahoud's leadership, Syria's efforts to mobilize mainstream Christians behind the presidency have failed miserably. To make matters worse for the beleaguered president, Hariri has sought to undermine Christian support for Lahoud by repeatedly declaring that Aoun can return to Lebanon without fear of arrest. After Hariri's most recent statement to this effect, Lahoud ordered a massive crackdown against the Free National Current and other anti-Syrian groups that resulted in over 200 arrests - causing Christian support for Lahoud to plummet even further. Despite his obvious political ineptitude, Lahoud still enjoys the full backing of Assad. But there is rampant speculation that Kanaan and other Syrian military and intelligence officials have encouraged the defiance of Hariri and his allies in the cabinet.

However, while Assad's primary objective of mobilizing Christians behind Lahoud has failed, his secondary objective of preventing any other public figure or institution from leading the Christian community has succeeded. Until recently, former President Amine Gemayel, who returned to Lebanon last year, appeared poised to resume his leadership of the once-powerful Phalange party. However, Lahoud and the Syrians managed to manipulate the party's elections in October and secure victory for a pro-Syrian candidate [see Damascus Co-opts the Phalange in the October 2001 issue of MEIB].

Notes

1 "US Is Lebanese Army's Patron," The Washington Post, 5 December 1998.

2 Al-Safir (Beirut), 22 September 2000.

3 Emile Lahoud, Address to the Arab Summit in Cairo, 21 October 2000.

4 The Daily Star (Beirut), 18 December 1999.