|

| Vol. 4 No. 9 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | September 2002 |

|

Despite its relatively weak presence in the West Bank and Gaza, the PFLP-GC has played a vital role in perpetuating the second Palestinian intifada by smuggling arms and explosives from Syria and Lebanon to Hamas and Islamic Jihad militants in the territories.

Current PFLP-GC Assets in Syria and Syrian-occupied Lebanon

The PFLP-GC, believed to have between 500 and 1,000 members, maintains offices in Damascus and the Yarmouk refugee camp outside the Syrian capital, as well as several major military bases around the country. Although journalists are frequently invited to the group's offices in Damascus, the exact locations of its training camps are cloaked in secrecy. In March 1989, two American diplomats who tried to photograph one of its bases (about 25 miles outside of Damascus) were abducted by PFLP-GC gunmen and held for over eight hours.1

The group also has an extensive political and military presence in Lebanon. Its headquarters are located in the Bourj al-Barajnah Palestinian refugee camp in the southern suburbs of Beirut and it maintains a modest armed presence in several other camps - particularly Al-Baddawi in north Lebanon, where Syria's military and intelligence presence is strong.

Unlike other Palestinian groups in Lebanon, the PFLP-GC has extensive military assets outside of the camps. Its largest base is located 9 miles (15 km) south of Beirut in the hills overlooking the coastal villages of Naameh and Damour, about 500 meters from the main coastal highway. The camp includes a fortified concrete underground arms depot built into the side of a mountain, a hospital and a welfare services center.

The group's second main base is located near the village of Sultan Yacoub in the eastern Beqaa Valley, about a mile or two from the Syrian border. Syrian-manned SA-2 and SA-6 surface-to-air missile batteries have long been positioned around its perimeter to deter Israeli air strikes (whereas the Israeli air force has bombed PFLP-GC bunkers south of Beirut dozens of times over the last decade, it abstained entirely from attacks on this base between 1990 and 1995 and hit it only a handful of times since).

Syria and the PFLP-GC (1968-2000)

The origins of the PFLP-GC date back to the 1959 establishment of the Palestine Liberation Front (PLA) by Ahmad Jibril. Born near Ramla in what is now Israel, Jibril moved to Syria in his teens and became a captain in the engineering corps of the Syrian army, where he developed ties with military figures who would later wield considerable power in Damascus. After launching a handful of ineffective attacks from Lebanon into Israel in the mid-1960s, the Syrian-backed PLA merged with George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December 1967.2

Tensions mounted almost immediately between Habash, a fiercely independent ideologue, and Jibril, who advocated armed conflict above all else and believed that the Palestinian struggle could not succeed without state sponsorship. In an apparent effort to strengthen Jibril's faction, the Syrians arrested Habash in Damascus in 1968, but after his return to Lebanon the two had a falling out and Jibril formed the breakaway PFLP-GC in December. Unlike his contemporaries, Jibril eschewed the intellectual freedom of Beirut (where most other Palestinian groups were then centered) and established his main headquarters in Damascus.

With Syrian financial, military and logistical support, the PFLP-GC quickly earned international notoriety for daring and brutal acts of international terrorism. In February 1970, it planted a time-bomb on a Swissair flight from Zurich to Tel Aviv, killing all 47 passengers and crew. In April 1974, it claimed responsibility for the first-ever Palestinian suicide bombing after three PFLP-GC militants strapped with explosives killed themselves and 18 hostages near Kiryat Shimona in northern Israel. Like most other Palestinian factions, the PFLP-GC largely abandoned international terrorism in the mid-1970s, focusing instead on infiltration into Israel from Lebanon.

While the PFLP-GC's early notoriety earned it a seat on the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) executive committee and central council, the group's political orientation squarely reflected the interests of its patron. Although Jibril endorsed a1974 PLO resolution pledging to establish a "national authority" in any area of the Palestine mandate conceded by Israel (an ambiguous statement that could be interpreted as either hinting at the possibility of negotiations or outlining a strategy of "stages" in the destruction of Israel), he abandoned all pretenses of moderation after prospects for a Syrian-Israeli peace agreement soured and Egypt began moving toward a separate peace with the Jewish state.

While Jibril's adamant rejection of any political solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict was construed by some Palestinians as advancing their interests, other decisions made by the PFLP-GC unmistakably advanced Syrian interests at the expense of the group's own proclaimed constituents. When Syrian troops invaded Lebanon and attacked Palestinian forces in 1976, the PFLP-GC openly endorsed the intervention - prompting a faction led by Mahmoud Zeidan (Abu Abbas) to leave the group and establish the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF). In 1983, after Yasser Arafat hinted that he was willing to negotiate with Israel, the PFLP-GC and a pro-Syrian breakaway faction of Arafat's Fatah movement (Fatah-Uprising) launched a bloody assault (backed by Syrian artillery) to drive the PLO chairman's loyalists out of northern Lebanon.

After its eviction from the PLO the following year, the PFLP-GC operated less as a Syrian-backed Palestinian group than as a Palestinian auxiliary of Syrian military intelligence. When Jordan's King Hussein signed an agreement with Arafat, Jibril's operatives were sent to infiltrate the kingdom and launch terror attacks. Following the 1986 Hindawi affair, which directly implicated high-level Syrian military intelligence officers in the attempted bombing of an Israeli El Al flight departing from London, Damascus relied on the PFLP-GC to continue its terror campaign against Israeli, Jewish and American targets in Europe.

During the latter half of the decade, poor economic conditions forced Syria to steadily reduce its financial support for the PFLP-GC and the group turned to other state sponsors for support. In 1986, it began receiving substantial support from Libya (which supplied the motorized hang-glider used by a PFLP-GC squad the following year to infiltrate Israel and kill six soldiers). However, following Libyan leader Moammar Qadhafi's public renunciation of terrorism in 1989, the group was forced to shut its training camps in Tripoli. Just two months later, Jibril met with Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati and, soon after, the PFLP-GC became the first Palestinian group to receive funds from Teheran.

The PFLP-GC's ties to Libya and Iran turned out to be an enormous blessing for the Syrian regime. When European authorities uncovered the group's infrastructure in Germany and Sweden and arrested dozens of PFLP-GC operatives in 1988 and 1989,3 there was sufficient ambiguity as to which government was directing the terrorists that Syria did not suffer the kind of diplomatic repercussions generated by the Hindawi affair (which prompted the US to withdraw its ambassador). Despite considerable evidence linking the PFLP-GC to the December 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland,4 British and American investigators charged Libyan intelligence agents with carrying out the terror attack.

|

Jibril continued to act as a mouthpiece for the Syrian regime in its efforts to discredit Arafat. In 1988, the group established a sophisticated radio station, Sawt al-Quds (Voice of Jerusalem), operating from a four-story building off Al-Malek al-Adel street in Damascus, with powerful transmitters in the suburbs that broadcast its signal across the Jordan valley to the West Bank. As Arafat inched nearer and nearer to direct negotiations with the Israelis, Jibril's criticism of the PLO leader began to more closely mimic the bizarre rantings of Syria's Ba'ath party. While many of Jibril's favorite mantras (such as his claim that Arafat is a Moroccan Jew imported by Israel's Mossad intelligence agency to control the PLO) were not taken seriously by most Palestinians, they greatly impressed his hosts.

The group's operatives were also used to subvert Palestinian organizations that deviated from Syrian "red lines." The assassinations of several officials of Arafat's Fatah movement in Lebanon during the early 1990s were (according to Fatah sources) carried out by Jibril's henchmen. In April 1995, according to one report, PLFP-GC agents were on the verge of assassinating Arafat himself after having infiltrated his security detail. Unfortunately for Jibril, the group had itself been penetrated by Egyptian intelligence, which promptly informed the PLO leader of the plot.5 After Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) Secretary-General Nayef Hawatmeh shook hands with Israeli President Ezer Weizman at the funeral of King Hussein in March 1999, members of the PFLP-GC, Fatah-Uprising and Sa'iqa attacked DFLP offices in Syria and Lebanon, killing one member of the group and injuring several others.

In Lebanon, the group was allowed to play a supporting role in fighting Israeli and Israeli-backed South Lebanon Army (SLA) forces in south Lebanon. After completing its military conquest of Lebanon in October 1990, Damascus allowed only the Lebanese Shi'ite Hezbollah movement to operate freely (most of the time) against Israel and the SLA. While most Palestinian groups were normally barred from launching operations in the South (or even maintaining a military presence outside of the refugee camps), a few hundred PFLP-GC guerrillas were permitted to operate against Israel in conjunction with Hezbollah throughout the 1990s.

While the PFLP-GC did not carry out any significant attacks inside Israel or the occupied territories during the 1990s, it played a key role in providing training and arms to those who did. Beginning in 1992, Hamas and Islamic Jihad terrorists have been trained at PFLP-GC camps in Syrian and Lebanon.6 Meanwhile, Jibril's operatives worked feverishly to smuggle weapons and explosives from Syria to their new allies in the West Bank. Between May and July 1996, Jordanian intelligence arrested dozens of PFLP-GC and Fatah-Uprising members and seized five vehicles that had been used to smuggle Semtex and other explosives into the kingdom from Syrian border crossings.

PFLP-GC militants were also implicated in terrorist activity intended to destabilize Jordan and disrupt its relatively warm relations with Israel. In May 1996, Jordanian intelligence uncovered a plot by the PFLP-GC and Fatah-Uprising to assassinate Prince Hassan and then-Prime Minister Abd al-Karim al-Kabariti, as well as bomb Israeli and American targets in the kingdom.7 In May 1998, Jordanian police again rounded up many PFLP-GC militants after the country was rocked by a month of terrorist strikes, including the assassinations of a prominent lawyer and a psychiatrist, arson attacks which destroyed the cars of a former intelligence chief and a former interior minister, and bombings of an American school, a police compound, and the four-star Al-Quds Hotel in Amman. Although Jordanian Islamists were later put on trial for the attacks, the PFLP-GC was widely believed to have provided the explosives.

In mid-July 1999, five months prior to the start of Israeli-Syrian negotiations in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, Syria was reported to have told the PFLP-GC and other radical Palestinian groups based in Damascus that they would have to adopt peaceful means of expressing their opposition to the Middle East peace process (apparently this was either an Israeli or American precondition). If this directive was anything more than a public relations ploy, however, it was clearly withdrawn following the breakdown of negotiations in 2000.

Bashar Assad and the PFLP-GC

In late 1998, as his health began to steadily deteriorate, Assad transferred what is commonly known as the "Lebanon File" (management of the regime's political and military surrogates in Syrian-occupied Lebanon) from Vice-president Abdul Halim Khaddam to his eldest son and heir apparent, Bashar.

The most pressing issue facing the new "high commissioner" of Lebanon was the rapid growth of Israeli public support for a unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon. After the May 1999 election of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, who had made a campaign promise to pull out by June 2000, an Israeli withdrawal became a near certainty. Strategically, this meant that the window of justification for Syria's proxy war against Israel would narrow considerably. While most Lebanese were willing to accept, if not support, Hezbollah's war against Israeli forces occupying Lebanese territory, Syrian officials feared that the war-weary population would not tolerate the continuation of hostilities by Hezbollah after an IDF withdrawal. Indeed, even Hezbollah's own Shi'ite constituency would likely oppose a continuation of military activity that invites Israeli retaliation and scares away international assistance and investment needed for reconstruction. Likewise, whereas international criticism of the Syrian and Lebanese regimes had long been muted by Hezbollah's claim to be resisting an illegal occupation, Damascus and Beirut would risk isolation if they sponsored attacks by Islamic militants into Israel itself. Abandoning its proxy war against Israel, however, would eliminate the Syrian regime's only tangible means of pressuring the Jewish state to make concessions at the negotiating table.

With the viability of Hezbollah as a future military proxy in doubt, Bashar decided to strengthen the most reliable alternative - the PFLP-GC. Since the group lacked an organized and reliable command and control structure in Lebanon (its guerrillas had mainly operated in conjunction with Hezbollah units), Jibril (who rarely visits the country) consolidated operational control over all PFLP-GC units and bases in Lebanon in the hands of his son, Jihad. Meanwhile, as Israeli preparations for a withdrawal steadily proceeded through the fall of 1999 and spring of 2000, Syria began a massive infusion of arms to PFLP-GC bases in the Beqaa. The Sultan Yacoub base near the border was heavily provisioned with outdated Soviet-built T-55 tanks and other heavy weaponry, while additional surface-to-air missile batteries were positioned around its perimeter.

The Israelis were deeply concerned about the growth of mechanized PFLP-GC units in the Beqaa ahead of their withdrawal from Lebanon and decided to strike. On May 20, 2000 - just three days before the IDF began pulling out of south Lebanon, Israeli air force jets bombed the Sultan Yacoub base, destroying ten tanks and killing three PFLP-GC guerrillas. Although some of the PFLP-GC's heavy weaponry survived the attack, the message to Damascus was clear - Israel would not tolerate a continuation of the war in south Lebanon by the PFLP-GC and other armed Palestinian groups.

The PFLP-GC and the Second Intifadah

|

Operations in the Palestinian Territories

Due to its lack of political autonomy in the eyes of most Palestinians, the PFLP-GC has never been able to attract a substantial following inside either the West Bank or Gaza strip. Since the beginning of the second intifadah, however, Israeli police have arrested a small number of Palestinian militants suspected of joining the group and training at PFLP-GC camps in Syrian and Lebanon.

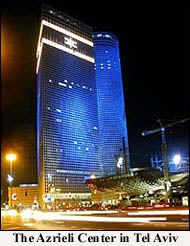

In at least one case, newly-recruited PFLP-GC members were ordered by their leaders in Damascus to carry out acts of terrorism inside Israel. In August 2001, Israeli police arrested two members of the PFLP-GC who were planning to bomb the largest commercial center in Israel. Mahmoud Salim Jibril (no apparent relation to the group's leader) and Rami Fawzi bin Said, both inhabitants of a refugee camp near Nablus, were returning from military training at a PFLP-GC base in Syria when they were arrested while crossing the Allenby bridge from Jordan to the West Bank. According to Israeli military sources, the two planned to destroy the 49-story Azrieli center, a three-building complex with a large indoor shopping mall, by planting explosives in the carpark.8

Arms Smuggling to the Gaza Strip

Since the outbreak of the second intifadah, the PFLP-GC has been the primary conduit through which Iran (and possibly Syria) have provided arms and explosives to Hamas and Islamic Jihad militants.

On May 7, 2001, Israel announced that it had seized a ship "sailing suspiciously" off its coast, discovering a 40-ton cache of arms, which included the following:

20 RPG-7 launchers

9 RPG-7 sights

100 RPG-7 rockets

50 OG-7 rockets

propellant for RPG-7 launchers

120 anti-tank grenades

4 SA-7 Strella anti-aircraft missiles

2 60 mm mortar

98 60 mm mortar shells

50 107 mm Katyusha rockets

62 TMA-5 mines

8 TMA-3 mines

24 hand grenades

30 Hungarian Kalashnikov assault rifles

116 Kalashnikov magazines

13,000 7.62 mm Kalashnikov rounds9

|

Anxious to bolster his standing among the Palestinians, Jibril publicly claimed responsibility for the arms shipment and boasted that the PFLP-GC had managed to smuggle similar shipments on three previous occasions. The Katyushas rockets, he said, were to be deployed against Israeli settlements. However, he went to great (and rather absurd) lengths to exonerate his Syrian patrons. Initially, he denied that the shipment had been sent from Syrian-occupied Lebanon, claiming at a May 9 press conference in Damascus that the arms originated "from a European port on board a European ship" which transferred its cargo to the Santorini 60 miles off the Lebanese coast.

The Syrians were apparently not pleased with Jibril's story - which would have led the Europeans to check shipping registries and press Damascus for more information about the mysterious European vessel. In an interview published the following day by the German newspaper Die Welt, Jibril admitted that the arms shipment had originated from Lebanon, but denied that Syria (or Iran) supplied the weapons, claiming that they were from stockpiles obtained from Libya during the 1980s.

Cross-border Attacks

Just weeks after the outbreak of the second intifadah in September 2000, Damascus authorized a resumption of cross-border attacks by Hezbollah forces in south Lebanon. However, due to intense pressure from the United States and growing opposition within Lebanon to the presence of armed Palestinian groups in the country, the Syrians have been very cautious about permitting the PFLP-GC to join the hostilities. The relatively few number of PFLP-GC operations authorized by Damascus have been intended mainly to "remind" both the US and the Lebanese population that Syria controls the level of hostilities in south Lebanon.

The first major PFLP-GC operation came on January 26, 2001, when two heavily-armed and uniformed members of the group were killed and a third wounded as they attempted to cross into the Shebaa Farms area of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Afterwards, according to local media reports, Lebanese President Emile Lahoud called Assad to "ask" for Syrian assistance in halting Palestinian attacks. The London daily Al-Hayat reported on February 2 that Syrian officials had delivered a "strongly-worded reproach" to Jibril and informed him that Damascus is opposed to "bringing the Palestinian military factor into play" in south Lebanon.

On March 12, 2002, after more than a year of relative PFLP-GC inactivity in south Lebanon, two Palestinian guerrillas (un-uniformed this time) crossed into Israel and opened fire on cars in the western Galilee, killing six Israelis before being hunted down and killed by the IDF. Although Israeli officials strongly suspected the PFLP-GC of launching the raid, the absence of any identifying evidence on the bodies of the gunmen made this impossible to confirm.

The "Mystery Missiles"

On April 4, 2002, in the midst of escalating hostilities in the West Bank and a new wave of cross-border attacks by Hezbollah, US President George W. Bush announced that Secretary of State Colin Powell would visit the Middle East on April 12, with stops in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco and Israel. The exclusion of Syria from Powell's trip was not well-received in Damascus - hours after Bush's announcement, the PFLP-GC was sent back into action against Israel.

Late in the evening on April 4, PFLP-GC guerrillas fired nine 107 mm GRAD rockets at an Israeli radar station on Mount Hermon in the Golan Heights - an area outside of the disputed Shebaa Farms area. The frenzied diplomatic activity which followed revealed a great deal about who controls security in Lebanon. Lebanese officials at first maintained a conspicuous silence as Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri met with Staffan de Mistura, the personal emissary of UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, no less than three separate times in twenty-four hours (apparently so as to consult with the Syrians between meetings). Meanwhile, 400 Lebanese troops were deployed to apprehend two PFLP-GC units that had been spotted by UNIFIL observers transporting more rockets toward the border.

The following day, however, two more of what the Lebanese press had begun calling "mystery missiles" were fired across the border into the western Galilee, wounding three Arab villagers in the town of Ghajar. Afterwards, PFLP-GC Deputy Secretary-General Talal Naji boasted that the group's fighters in Lebanon "have arms, rockets and long-range artillery" and "have the right to use them" in an interview with the Saudi-owned MBC television station.

On April 7, US Ambassador Vincent Battle held a 45-minute "crisis talk" with Hariri and the Lebanese foreign and defense ministers and received yet another commitment to prevent the PFLP-GC from launching cross-border attacks. The next day, however, PFLP-GC guerrillas fired a Katyusha rocket at the Israeli border town of Kiryat Shimona.

Despite a great deal of rhetoric by Jibril and other PFLP-GC officials in the days that followed, there were no further PFLP-GC attacks. It is not difficult to discern why - Syria and Lebanon were added to Powell's itinerary. A week later, after completing his other stops, the American secretary of state arrived in Damascus on April 15 in order, he said, "to exchange views" with Syrian officials and hear "their assessment" of the regional situation.11

Israel Strikes Back?

|

Hours after the attack, Jibril told Qatar's Al-Jazeera television network that Israel was responsible for assassinating his son with assistance from Jordanian intelligence, which he said had become "a tool in the hands of the Mossad and US intelligence." He added that the PFLP-GC had previously arrested Jordanian agents in Lebanon but did not elaborate on the claim (which has been categorically denied by Israeli and Jordanian officials).

Strangely, in subsequent interviews and remarks at the funeral, both Jibril and Naji not only boasted that Jihad was the mastermind behind arms shipments to Gaza and "had ordered the firing of rockets at Israeli positions" (activities which the PFLP-GC had previously acknowledged), but, in their zeal to enshrine Jihad as a martyr to the Palestinian cause, openly bragged that he was in charge of training Hamas fighters at PFLP-GC bases in Lebanon (which the PFLP-GC had not publicly acknowledged before).12

If the Mossad was indeed responsible for the assassination, then it is clear that Israeli agents had penetrated the PFLP-GC much more thoroughly than ever before. Shortly after the killing, the PFLP-GC's security apparatus in Lebanon arrested Amer Arraji, a close friend of the deceased, and his Palestinian driver, Khaled Kawash. Both were brought before Syrian intelligence officers under the command of Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan and interrogated thoroughly before being transferred into the custody of Lebanese police (a typical routine in security cases).13 There has since been a virtually complete media blackout on the investigation, suggesting that the Syrians are hoping to recruit any additional accomplices as double agents.

Whoever was responsible for the assassination, it is doubtful that it will have a significant impact on PFLP-GC activities - which are governed less by the whims of Jibril and other figures in its leadership than by decisions made at the highest levels in Damascus and Teheran.

Notes

1 See The Washington Post, 10 March, 11 March and 13 March 1989.

2 For more background on the PFLP-GC, see David Tal, "The International Dimension of PFLP-GC Activity," in INTER - International Terrorism in 1989 (Tel Aviv: The Jaffe Center for Strategic Studies & The Jerusalem Post, 1990), pp. 61-77. An online version of this article is available on the web site of the International Policy Institute for Counter-Terrorism.

3 In October 1988, German police raided a PFLP-GC safe house and arrested 16 of the group's operatives - two of whom, Hafez Kassem Dalkamoni and Abdel Fattah Ghadanfar, were later convicted of carrying out bomb attacks against US military trains in Germany in 1987 and 1988. In May 1989, Swedish police arrested 15 members of the PFLP-GC and the Palestine Popular Struggle Front (PPSF) linked to attacks on Israeli and American air line offices (operatives of the two organizations collaborated so closely in Stockholm that Swedish investigators never determined their affiliations with certainty).

4 See Gary C. Gambill, The Lockerbie Bombing Trial: Is Libya Being Framed? Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, June 2000; Ian Ferguson, The Lockerbie Bombing Trial: New Problems in the Prosecution's Case, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, September 2000.

5 See The Intelligence Newsletter, 14 November 1996.

6 The earliest direct evidence of this came to light with the arrest of Islamic Jihad member Sami Kamel al-Habib by Israel in March 1995. Under interrogation, Habib said that he and other Islamic Jihad members traveled to Syria in 1992 for military training at a PFLP-GC camp.

7 Sawt al-Mar'a (Amman), 24 July 1996.

8 Ma'ariv, 21 September 2001.

9 IDF Press Release, 7 May 2001.

10 Ha'aretz (Tel Aviv), 9 May 2001.

11 AFP, 15 April 2002.

12 AFP, 22 May 2002.

13 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 25 May 2002.