|

| Vol. 4 No. 9 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | September 2002 |

|

Recently, however, a new political challenger has arrived on the Lebanese scene who possesses all three of these strengths in greater degree. Saudi Prince Al-Walid bin Talal, whose mother is Lebanese, has not formally applied for the job - but he has impressed the boss and is getting along famously with the staff.

Background

Since Hariri's return in 2000 as prime minister, a post constitutionally reserved for a Sunni Muslim, tensions between the premier and Damascus have been manifest. Although post-civil war constitutional amendments ostensibly give the Lebanese prime minister official oversight of the military, Syria awarded control over security matters to President Lahoud and its hand-picked sycophants in Lebanon's military-intelligence apparatus in order to ensure that the opposition is kept in check and pave the way for Hezbollah's resumption of cross-border attacks against Israel.

Anxious to attract international investment to Lebanon, the prime minister objected to Hezbollah's resumption of cross-border hostilities with Israel in the fall of 2000. When Hariri began expressing this position openly early last year,1 Syrian President Bashar Assad angrily canceled a scheduled meeting in Damascus and refused to speak with him for over a month, while Syrian officials met publicly with his rivals. Tensions exploded again in August 2001, when Lebanese security forces arrested over 250 opposition activists while Hariri was abroad.

Syrian officials were reluctant to remove the prime minister, however. Hariri, a billionaire who made his fortune in the Saudi construction industry, not only retained considerable support from the Sunni community in Lebanon, but was strongly favored in international financial circles and backed by both the United States and Saudi Arabia. No other figure in Lebanon could boast such credentials.

Syria's New Hope?

It is not entirely clear when Prince Al-Walid first came under active consideration as a replacement, but the first indication that Hariri was on his way out came early this year, when President Lahoud began floating the idea that his term as president, scheduled to end in 2004, be extended beyond the constitutional limit of six years - a proposal which met with approval in Damascus and outright defiance from Hariri.

Al-Walid was hardly unknown in Lebanon. His divorced mother, Mona al-Solh, is the daughter of Lebanon's first post-independence prime minister and has continuously resided in the country for decades. A frequent visitor to the country and sponsor of many charities, the prince earned rave reviews in 1999 when he provided the Lebanese government with $7 million dollars to repair two power plants damaged by Israeli air strikes. However, his previous attempts to buy political influence were thwarted. In the mid-1990s, he attempted unsuccessfully to acquire a 50% stake of Dar Assayad, one of Lebanon's leading publishing houses, by registering the shares in his mother's name (Lebanese law prohibits foreigners from investing in local media). After years of litigation, the Civil Appeals Court ruled that Mona al-Solh's name "was only assumed as a facade" for Al-Walid and blocked the move.

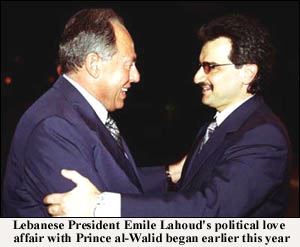

Earlier this year, however, the Lebanese press suddenly began reporting that the prince held dual Saudi-Lebanese citizenship and was interested in playing a political role in Lebanon. On the eve of the March 2002 Arab League summit meeting in Beirut, Al-Walid arrived in Lebanon and held private talks with President Lahoud, who shortly afterwards awarded him the prestigious Order of the Cedars medal in recognition of his assistance to the Lebanese people. At a news conference after the ceremony, the prince criticized Hariri's economic policies. Afterwards, he visited Druze leader Walid Jumblatt and the Mufti of Lebanon's Sunni Muslim community, Sheikh Rashid Qabbani, presenting the latter with a $2 million check to build a new mosque in Beirut. He declined to pay Hariri a courtesy visit.

The prince's criticism and his attempt to ingratiate himself with the top Sunni religious leader in Lebanon outraged Hariri. Shortly thereafter, supporters of the prime minister staged large demonstrations denouncing the prince by name outside Dar al-Fatwa, the headquarters of Qabbani.

In the aftermath of the demonstrations, Lebanese and Arab journalists who asked Al-Walid if he aspired to become prime minister of Lebanon received the same reply: "we'll cross that bridge when we come to it," a remark which appeared intended to fuel speculation that he had it in for Hariri. According to some in the Lebanese media, President Lahoud and the security services have also sought to fan the rumors. Mysteriously, large numbers of posters bearing the image of the prince and the slogan "You are our hope!" began to pop up in Sunni neighborhoods of West Beirut. In recent interviews, some Beirut newspapers have addressed the prince as "Your Excellency," a term normally reserved for heads of state.

Over the next few months, the prince continued his efforts to buy influence in the country. On May 3, his office announced that he had donated $1 million to 22 Lebanese charities. Later that month, he purchased a 10% stake in Al-Nahar, Lebanon's leading mass-circulation daily newspaper.2

In late May, the dispute reached new heights of absurdity. During an economic conference in Beirut, a Saudi businessman rose and asked Hariri a question "with the greetings of Prince Al-Walid." Soon afterwards, the prince fired off a press release denying that he had conveyed his greetings to the prime minister and emphasizing that he does not need an intermediary with Lebanese officials.

On July 2, Al-Walid again sent shock waves through the Lebanese media at the inauguration of his newly-built $140 million Movenpick hotel in the Raouche district of Beirut. After a laser show and barrage of fireworks that lit up the sky over the capital, he addressed an audience of Lebanese political elites and top military brass which conspicuously excluded Hariri. The prince began his speech by saying that he did not "pretend to be qualified to offer advice to the government of Lebanon," adding that "one demonstration is enough." However, he subsequently declared that the Lebanese government must outline a 5 or 10-year economic plan that would "make clear to all Lebanese and all investors the broad outlines of the economic situation" and introduce privatization of the public sector in stages. Finance Minister Foaud Siniora, he said, "should begin working in this direction."

"Every investor has the right to feel secure about his investments. It is the duty of the state and the government to provide this safety," he continued. "The investor is like a citizen, he wants to know where the state economic (policy) is heading." The implication of these remarks - that those in charge of economic policy in Lebanon had failed both citizens and investors - was lost on no one. Equally telling was Lahoud's behavior during the event. He would later be criticized in the media for smiling contently during the speech and breaking presidential protocol by walking behind the prince. The following day, Al-Nahar called the prince's speech "a policy statement," as if he were a prime ministerial candidate seeking a vote of confidence from parliament.3

Asked about Al-Walid's political ambitions by a reporter, Hariri abruptly replied "next question!" The prime minister, who is rarely at such a loss for words in public, later told Al-Safir, "I accept critical statements from anyone who builds a hotel in Lebanon," when asked to comment on the prince's speech.4 Notwithstanding the premier's feigned nonchalance, the Lebanese media speculated that Hariri would raise the issue in a subsequent visit to Saudi Arabia.

In July, Al-Walid took offense when Hariri's Future Television network referred to him merely as "the owner of Beirut's Movenpick Hotel." Later that day, his press office in Riyadh issued a statement pointing out that while the prince "takes pride in owning Beirut's Movenpick . . . he also sits at the helm of a business empire of 1,300 companies spaced across five continents." The same statement later referred to the Lebanese prime minister as the owner of Saudi-Oger, Hariri's Saudi-based contracting company.

Having previously restricted his criticism of Hariri's policies to broad generalities, in late July Al-Walid openly condemned Hariri's plan to privatize the mobile telephone sector, mimicking Lahoud's argument that the state would not be able to derive sufficient revenue from the sale of operating licenses due to global economic conditions.

Whether Al-Walid's entrance into Lebanese politics is intended to replace, or merely weaken, Hariri remains to be seen, but it is clear the prime minister has met his match politically. Hariri has fended off challenges from other Sunni politicians in Lebanon primarily by outspending them - a familiar tactic that would be futile against a prince with five times his own net worth. Another powerful resource employed by Hariri at many critical junctures in his political career to prevail over opponents - his ties to the Saudi royal family - has also been negated in the confrontation with Al-Walid.

Notes

1 In February, Hariri declared to group of investors in Paris that "there will be no provocations on our part." Two months later, his newspaper criticized Hezbollah attacks in a front-page editorial See Nicholas Blanford, "Hizbullah Hoist by Its Own Petard," The Middle East, April 2001; Al-Mustaqbal (Beirut), 15 April 2001.

2 The other major shareholders are the Tueni family (36%), Hariri (33%), and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Beirut (18%).

3 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 3 July 2002.

4 Al-Safir (Beirut), 4 July 2002.