|

| Vol. 4 No. 3 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | March/April 2002 |

|

Background

For over fifty years, Syrian leaders have refused to normalize diplomatic relations with Lebanon, declining either to exchange embassies or make official visits to the country. The last official visit to Beirut by a Syrian head of state was in 1947, when then-President Shukri al-Quwatli traveled to the Lebanese capital. Over the next quarter century, Quwatli and his successors made a handful of unofficial visits,1 but the late President Hafez Assad stepped foot in Lebanon only once during his 30-year tenure - in January 1975, he crossed the border briefly to meet with his Lebanese counterpart, Suleiman Franjieh, in Shtaura. He later remarked that he "had the feeling of going from one town to another within a single country, of leaving one portion of my people for another."2 The following year, Syrian military forces swept into Lebanon.

Syria's refusal to normalize diplomatic relations with Lebanon has been motivated in part by an unwillingness to fully acknowledge Lebanon as an independent legal entity on par with neighboring Arab countries. While Damascus has been obliged by international legal norms to formally acknowledge Lebanon as an independent state, its failure to extend such symbolic forms of recognition allowed it to maintain a deliberately ambiguous stance regarding Lebanese sovereignty.

The refusal of Syrian heads of state to make official visits to Beirut and the absence of a resident Syrian ambassador in the Lebanese capital have also served the narrow interests of Syria's military intelligence apparatus in Lebanon, which has established de facto control over the Lebanese government and has long operated with varying degrees of autonomy from Damascus. With the exception of a handful of Lebanese heavyweights who have direct access to the Syrian president (and therefore travel to Damascus frequently), Lebanese politicians and businessmen who wish to appeal to the Syrians must do so through the commander of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, or one of his subordinates. As a result, Kanaan and other Syrian military intelligence officers in the country have grown immensely wealthy from bribes and other illicit activities.

Why Now?

Assad initially intended to make his first visit to Lebanon as Syrian president during the March 27-28 Arab summit meeting in Beirut - the bilateral visit on March 3 was hastily arranged and announced only hours before his arrival. Attending the summit would not have been an official state visit, per say, but more akin to a foreign head of state arriving in New York to speak before the United Nations.

But the Arab summit meeting would not have been scheduled to take place in Beirut late last year without the approval of Damascus, which strictly controls the Lebanese government's foreign policy. And, presumably, Assad would not have approved holding the summit in Lebanon unless he was planning to attend it. Assad's decision to break with Baathist tradition and step foot in Lebanon was therefore integrally linked to his approval of Lebanon's bid to host the summit. This, in turn, appears to have been motivated by the Syrian leader's desire to mobilize a unified Arab policy toward the Palestinian uprising against Israel (Beirut, which is more or less Syrian "home turf," would provide an ideal setting for such an endeavor).

It appears that there were some in the Syrian regime who originally opposed plans to hold the summit in Beirut. In late December 2001, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri began calling for the summit to be postponed shortly after returning from a trip to Damascus, ostensibly because he felt that the event might be harmful to the "Lebanese resistance." However, Berri's calls for a postponement were "believed to have been instigated by Damascus," reported one Lebanese newspaper, citing political sources. "The speaker's assertions that he had not discussed this issue with Syrian officials rang hollow."3

Assad's arrival in Lebanon was also intended to serve other objectives. Syria has long sought to pressure and entice traditional Christian political and religious elites into accepting Syrian hegemony in Lebanon, since this would in turn undermine popular support for the Lebanese nationalist movement within the Christian community (still its center of gravity). While some of these elites have gravitated toward the nationalist opposition movement, particularly in the last two years, most have expressed a willingness to accommodate themselves to Syrian hegemony as long as observable manifestations of this hegemony are reduced - making it easier to justify cooperation with Syria to their constituents (the vast majority of whom strongly oppose the Syrian regime). Syria's partial redeployment of troops from Beirut to eastern and northern Lebanon last year (some have since returned to the capital) was clearly intended to set this process in motion. While attending the Arab summit would not be the official state visit that many of these elites have called for, it would nevertheless reduce somewhat an observable dysfunction in the relationship with Syria and thereby potentially undermine the nationalist movement.

A second consideration that may have prompted the Syrian president to end his refusal to visit Lebanon was growing internal divisions in the regime, which have obstructed much-needed economic reforms and further undermined public confidence in the government. Intense quarrels between President Emile Lahoud, to whom the Syrians have granted exclusive oversight of security policy, and Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri (and, to a lesser extent, between each of them and Berri) have erupted repeatedly over the last two years, particularly after Lahoud ordered a crackdown on nationalist opposition forces in August 2001 without consulting, or even informing, Hariri (who was out of the country at the time).

In the past, domestic political squabbles in Lebanon have prompted mediation by Maj. Gen. Kanaan, or occasionally Vice-President Abdul Halim Khaddam. However, fissures within the regime have repeatedly burst into the open since Assad's ascension, and it is clear that they are fueled in part by the fact that Kanaan, Khaddam and other Syrian officials often align with different factions. Assad, who controlled the "Lebanon file" and was a frequent visitor to Beirut prior to succeeding his father, may have decided that continuing Syria's traditional moratorium on official state visits to Lebanon was hampering his authority over both the Lebanese regime and the Syrian military-intelligence apparatus.

The decision to make a full-fledged bilateral visit prior to the summit appears to have reflected additional considerations. First, the release of Crown Prince Abdullah's peace proposal in mid-February had, by the end of the month, set the agenda for the summit in Beirut and cast the Saudi crown prince as its de facto keynote speaker. Arriving in Beirut for the first time as a bit player while the spotlight shone on someone else was not the grand entrance into Lebanon that Assad had in mind. Making a prior visit would therefore prevent his first trip to Lebanon from becoming second page news.

Second, it became critical that the Syrians prevent any embarrassing manifestations of opposition to Syrian hegemony from erupting either before or during the summit. Since a bilateral visit would be a stronger form of symbolic diplomatic recognition than attending the summit, this made it easier to persuade Christian elites to oppose demonstrations against the occupation, at least until the summit was over.

Finally, in the weeks prior to Assad's visit, major fissures within the Lahoud faction of the regime began to erupt for the first time, most notably between the president and Health Minister Suleiman Franjieh. The first signs of a quarrel brewing were false reports in the Lebanese press, leaked by security sources, that an assassination plot against Franjieh had been uncovered, prompting him to angrily denounce the security apparatus as made up of "dogs." It appears that the dispute arose from Franjieh's declaration that he intends to run for president after the expiration of Lahoud's term in 2004, followed by reassurances that he will "tag along" if the Syrians extend Lahoud's term (which, needless to say, the president did not appreciate).

It also noteworthy that Brig. Gen. Jamil al-Sayyid, the director-general of Lebanon's General Security Directorate (GSD) and constant companion of the Lebanese president (he even accompanied Lahoud on a state visit to the Vatican, where security issues were presumably not discussed), has virtually disappeared from the president's side, at least publicly, in recent months. Since Sayyid's primary job is to spy on Lahoud for the Syrian regime, this is a significant development. According to one informed Lebanese source, Sayyid was sidelined after a quarrel with Kanaan.

The Visit

Assad's visit was laden with symbolism. Rather than crossing into the country overland, as his father did in 1975, Assad arrived like a visiting head of state, landing at Beirut International Airport at 10:30 AM. He was accompanied by Prime Minister Muhammad Mustafa Miru, Foreign Minister Farouk al-Shara, Parliament Speaker Abdelkader Qaddoura, as well as a number of journalists. The Syrian leader was welcomed at the airport by 21-gun salute and a delegation headed by President Lahoud, Prime Minister Hariri, and Parliament Speaker Berri and dozens of ministers, senior government officials and parliamentary deputies.

After reviewing a Lebanese honor guard, Assad set another precedent by traveling to the presidential palace at Baabda, a symbol of Lebanese sovereignty that none of his predecessors had ever entered, to meet privately with Lahoud.

Assad and Lahoud then chaired the fourth meeting of the Lebanese-Syrian Higher Council, the first time that the body has convened in Lebanon (its three previous sessions were held in Syria). The meeting began with a moment of silence in memory of Assad's father. During the meeting, the two presidents signed an agreement which stipulated a number of joint economic ventures, including plans to construct two dams on the Assi (Orontes) and Nahr al-Kabir rivers, a textile factory in Akkar, a tobacco processing plant in the Beqaa and two refineries in Sidon and Tripoli.

As a "gift" to Lebanon, Assad waived half of Lebanon's unpaid $120 million bill for electricity imports from Syria and declared that the price set for Syrian exports of natural gas to Lebanon would be "reconsidered." The electricity waver was portrayed in local press as an idea that the Syrian president suddenly thought of while en route to Lebanon and kept to himself before announcing it unexpectedly - a spin clearly designed to present Assad as a benevolent figure who can change Syrian policy in Lebanon at the slightest whim.

Another widely-publicized "concession" by the Syrian president concerned the estimated 1.4 million Syrian workers who reside illegally in Lebanon, contribute to the country's soaring unemployment rate, and pay no taxes or work permit fees, depriving the Lebanese economy of billions of dollars each year. As a result of the ongoing economic crisis in Lebanon, Syria's unskilled laborers have begun to elicit far more hostility among the masses in Lebanon than its soldiers (seven workers have been murdered since last summer). Assad was reported to have told Lebanese officials at the meeting to "take whatever measures you want" with regard to Syrian workers in the country. Of course, this seemingly magnanimous offer was of the kind that cannot actually be accepted (ostensibly, Lebanese officials are also welcome to request the withdrawal of Syrian soldiers from Lebanon).

Although the official statement released by the council did not explicitly mention the Saudi peace proposal, it declared that "any attempt to end the Arab-Israeli conflict should rely on the bases that help achieve a complete liberation of all occupied Arab lands, secure the right for Palestinian refugees to return to their homeland, and allow the creation of an independent Palestinian State with Jerusalem as its capital."

After the meeting, the two presidents went to the Ambassadors Hall of the presidential palace and exchanged decorations. Lahoud presented Assad with the Lebanese Order of Merit of Extraordinary Degree (the highest honor bestowed by the Lebanese government), while the Syrian president awarded his counterpart the grand Cordon of the Order of the Umayyads. Assad then signed the "Golden Book" at the presidential palace as follows: "Present at Baabda Palace on the occasion of the convening of the Lebanese-Syrian Higher Council, I am happy to address a brotherly greeting to my brother, General Emile Lahoud, and to the fraternal Lebanese people. I wish the people of Lebanon continual prosperity and the strength necessary to confront the present challenges. I take pride in my visit to this fraternal country, the first since my accession to the presidency of the Syrian Arab Republic, and I am confident that cooperation between Syria and Lebanon will continue on all levels for the good of our two brotherly peoples."

Early in the afternoon, Assad returned to Damascus overland as Syrian military helicopters flew over the convoy at low altitudes.

Reaction

Lebanese officials portrayed Assad's visit as having quelled fears that Lebanese sovereignty has been compromised by the Syrian occupation. On March 7, Prime Minister Hariri told Qatar's Al-Jazeera satellite television network that Assad's visit had "an enormous positive impact, eliminating all doubts cast regarding Syria's stand vis-à-vis Lebanon's independence and sovereignty." Deputy Prime Minister Issam Fares proclaimed that the Syrian president's six-hour trip "will surely spread a sense of well-being and dispel the fears and obsessions of those who have hitherto had doubts about Syria . . . it is a further guarantee which should disperse the clouds troubling the atmosphere of Lebanese-Syrian relations, which will in the future be characterized by transparency and confidence."4

Most media commentators and political elites outside of the government also welcomed the visit as a significant step toward improving relations with Syria. However, some mainstream Christian public figures tempered their approval of Assad's visit with a palpable note of caution. Al-Nahar editor Gibran Tueni, who has openly called for Syrian troops to leave Lebanon, called it "the first step toward correcting the Lebanese-Syrian relationship," but added caustically his hope that it signifies that "Syria no longer views Lebanon as one of its provinces."5 Maronite Patriarch Nasrallah Butrous Sfeir, who re-emerged as a vocal critic of the Syrian occupation last fall, welcomed the visit as "a step that helps develop the Lebanese-Syrian relationship," but reiterated his call for the redeployment of Syrian military forces to the Beqaa Valley in eastern Lebanon, as stipulated by the 1989 Ta'if Accord. "We need to feel that decisions in Lebanon are free and not being commandeered," he added.6

However, Nationalist opposition leaders were not impressed by the Syrian dictator's brief sojourn in Lebanon. The head of the Free National Current, Former Prime Minister Michel Aoun, said from exile in Paris that "it is difficult to know whether it was a visit to a Syrian province or a sovereign state."7

Did Assad Miscalculate?

Assad's visit to Lebanon may have been a successful public relations ploy for external consumption, projecting a veneer of sovereignty onto Syria's satellite regime in Lebanon, and appeased Lebanese political elites pressing for cosmetic reforms of a system that they have a stake in preserving. However, it does not appear to have diminished broad-based opposition to Syrian hegemony and or smoothed over any rifts within the regime.

|

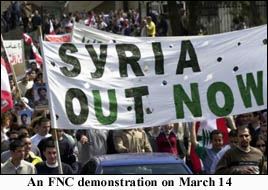

Nevertheless, the FNC went forward with the march, which drew an estimated 2,000 participants, mostly students, despite a large deployment of security forces. Meanwhile, Aoun issued an unprecedented statement from Paris, declaring that "the beginning of the end for Syria's occupation of Lebanon" has arrived.

On March 19, the president of St. Joseph University, Father Selim Abou, issued by far the most direct denunciation of Syrian hegemony by a prominent Maronite Christian cleric in over a decade. "The Syrianization of Lebanon has gone much too far and is still expanding," said Abou in his annual address on St. Joseph's day before a packed auditorium. "Lebanese and Syrian intelligence agencies operate in full tandem and Lebanon has implicitly given up its independence and democracy." Abou also warned that Lebanon's army is becoming Syrianized. "Gone are the days when our officers went to France or the United States for specialized training courses. Over the past decade and a half, they have been sent to Syria for indoctrination in Baathist ideology."8

The following day, the Lebanese Army Command issued a statement warning Abou "to exercise precision and objectivity before airing such opinions, which cause despair and mislead students and young people, rather than teaching national consciousness and respect for the patriotic role of the army." This prompted hundreds of St. Joseph University students to demonstrate in the streets of Beirut in support of Abou.9

|

While Assad's visit yielded a collective sigh of relief among the ruling elite in Lebanon, it did little to ameliorate internal divisions in the regime. In fact, it appears to have exacerbated them.

Hariri's feud with Lahoud was re-ignited by the visit. After Assad's departure, the prime minister openly complained that he was excluded from the Syrian president's one-on-one meeting with Lahoud, which lasted an hour and forty minutes. During the preparations for the summit, Lahoud unilaterally selected members of the Lebanese delegation, excluding several cabinet ministers close to Hariri. Just days before the summit, sources close to Lahoud leaked rumors of an impending cabinet reshuffle that outraged the prime minister. The next clash occurred on the first day of the summit, when Lahoud excluded Hariri (and Berri) from one-on-one talks with visiting Arab heads of state, prompting both to boycott reception ceremonies at the airport.

Tensions also flared between Lahoud and Information Minister Ghazi Aridi, an ally of Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, over the distribution of mysterious leaflets accusing Aridi of collaboration with Israel. Jumblatt accused the security services (and, by implication, the president) of responsibility for the leaflets.

Within the Lahoud camp, the feud between the president and Health Minister Franjieh has continued to escalate. Less than a week after Assad's visit, Lahoud vetoed a plan to open 36 new medical centers built by Saudi donations in the 1990s, claiming that the cost was too high and the "geographic distribution" of the facilities imbalanced. After Franjieh demanded a cabinet vote, Lahoud replied, "You are not entitled to demand a vote. I am the president, I am presiding over the session, and I am the one with the right to call a vote." Franjieh stormed out of the room, telling reporters, "The plan was rejected only because Suleiman Franjieh is health minister."10

Notes

1 Contrary to Western news reports, which called Bashar Assad's visit the third by a Syrian head of state, Lebanese media reports say that Quwatli made two subsequent unofficial visits in 1947 and 1956 (during his second tenure as president). President Fawzi Silu entered the country briefly in 1952 and President Noureddin Atassi made two quick visits, in 1967 and 1970.

2 Radio Damascus, 17 July 1986. Cited in Daniel Pipes, Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition (Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 120.

3 The Daily Star (Beirut), 3 January 2002.

4 Monday Morning (Beirut), 11 march 2002.

5 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 7 March 2002.

6 The Daily Star (Beirut), 5 march 2002.

7 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 4 march 2002.

8 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 20 March 2002.

9 The Daily Star (Beirut), 21 march 2002.

10 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 8 march 2002.