|

| Vol. 3 No. 2 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | February 2001 |

| Thomas Patrick Carroll is a freelance writer and former officer in the Clandestine Service of the Central Intelligence Agency. His areas of specialization are Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean affairs. |

The Turkish Republic is awash in antiquities. From Hittite fortifications and Lycian rock tombs, to Ottoman baths and Phrygian granaries, the entire country is a treasure trove of priceless fragments from past millennia. In the post-Cold War world of today, however, the most fascinating historical relic in Turkey is not made of bronze or marble, but of beliefs and ideology. That relic is the radical political left.

This is not the chastened, defanged left that one sees elsewhere. We are not talking about the 'pink Tories' of British Prime Minister Tony Blair's Labour Party, or those tame social democrats sprinkled across Europe. To be sure, the majority of leftists in Turkey are of this moderate social democratic variety. In fact, the current ruling party in Turkey is the Democratic Left Party, led by Bulent Ecevit, which advocates moderate, democratic socialism.

|

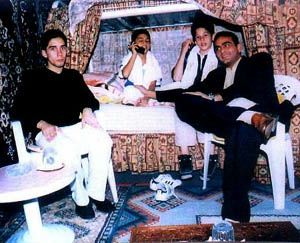

| Two sons of notorious gang leader Nuri Ergin--Nurettin, left, and Vedat, right--relax in luxurious surroundings at Usak prison in western Turkey last year [Hurriyet] |

In fact, until quite recently, gangs of leftist inmates actually ran the show inside most of Turkey's major jails and prisons, sharing power with drug dealers, Islamic militants and other incarcerated blocs of dangerous (and well-organized) pariahs and malcontents. In late December 2000, however, the Turkish government brought this extraordinary state of affairs to a fiery and spectacular end. It did so with a violent paramilitary operation, the aftershocks of which will reverberate for a long time to come.

Background

Turkey's prisons have been spinning out of control since the late 1970s, when extremist political violence, coming from both the left and the right, swept the country. It was then that the state began filling its prisons with political fanatics.

The prisons were overcrowded. Inmates were not housed in cells, but in large, open dormitories under the control of revolutionary gangs. Prison authorities were powerless to intervene. Weapons, drugs, and all manner of contraband flowed freely. Leftwing political thugs ran the dormitories as recruiting and indoctrination centers, routinely administering their own style of revolutionary 'justice'--beatings, torture, executions, extortion, and occasional hostage-taking.

By 1996, even Interior Minister Ülkü Gülcügil acknowledged that the world inside Turkish prisons was controlled by revolutionaries and that the state was no longer in command.1

Of course, not every political activist sent to prison was a violent bomb-thrower. A young militant could just as easily be incarcerated for hanging a banner with a revolutionary slogan as for shooting a policeman. Unfortunately, these nonviolent activists were thrown into dormitories run by bloody extremists, effectively enrolling these relatively innocent neophytes in "schools for anarchy", as former Turkish President Suleyman Demirel aptly termed the prison wards.2

F-type Prisons

The state could not let this go on forever. Recognizing that much of the problem lay in the very design of the prisons themselves (i.e., the mass housing in open dormitories), in the 1990s the central government in Ankara decided to build modern incarceration facilities. Hence was born the 'F-type' prison.

Turkey's new F-types are much like any maximum-security prison in Western Europe or the United States. The old dormitories housing scores of prisoners in one common room are gone in the F-types, replaced with individual cells designed to hold two or three. And without the mass housing, Ankara reasoned, control over prisoners by the gangs would be far more difficult, if not impossible. Authority within the prisons would return to the hands of the state, said Minister of Justice Hikmet Sami Turk.

As one would expect, there were many people--the leftwing prison gangs, most conspicuously--who did not see this as an improvement. The main complaint, at least publicly, was that F-type prisons would isolate the inmates from each other, making it easier for guards to brutalize them. Human rights organizations and European governments made this point. So did various prisoner advocacy groups inside Turkey, like the Detainees and Inmates Solidarity Association, and the Union of Inmate Families.

The danger of guards beating up isolated prisoners was real enough. Problems of this sort exist in every jail from Baifra to Beverly Hills, and especially in developing countries like Turkey, where law enforcement officers are paid abysmal wages and prison conditions are low on everyone's list of public priorities. Official brutality is definitely a problem inside Turkish prisons, no doubt about it. But the opinions of human rights organizations and inmate families were of secondary importance. The groups whose views really mattered were the leftist gangs that controlled the old system, and they saw the new F-type institutions--quite correctly--as a threat to their power. The gangs responded with hunger strikes.

Self-Starvation

Hunger strikes are not an unusual political weapon in Turkey. Labor unions use them, for example, as do other groups. Prisoners engage in them as well. In October, about 800 radical leftwing inmates in 14 Turkish prisons began starving themselves to protest the government's plans to move them into the new F-type prisons. Relatives of the prisoners and human rights activists also joined in.

Weeks went by and the hunger strikes began to have their intended political effect. The government in Ankara got nervous. As noted earlier, these imprisoned leftists were hardcore, and if they said they would starve themselves to death, they jolly well would. And since Turkey is forever fretting about its human rights image in Europe, the last thing Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit wanted was Amnesty International holding rallies in Brussels calling attention to hundreds of dying communists in Turkish prisons.

On 13 December, in an effort to defuse the increasingly volatile situation, Justice Minister Hikmet Sami Turk said the government would postpone the opening of the F-type prisons. The announcement might have presented a reasonable opportunity for the inmates (or their representatives) to negotiate, but hunger-striking communists are not known for their dispassionate reason. The prisoners continued their self-induced starvation.

Amnesty

But the government in Ankara had other cards in its hand.

In December 2000, Turkey had 72,000 inmates in its crowded, antiquated prison system. The shifting of inmates to F-type prisons clearly would be much easier if there were fewer inmates to shift--an obvious reason to get rid of some prisoners.3

As luck would have it, Rahsan Ecevit, wife of Prime Minister Ecevit, had proposed a wide-ranging amnesty just a couple of years before. The bill that was finally produced by the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA) was flawed, and was vetoed in September 1999 by then-President Suleyman Demirel.

The TGNA went back to work, and on 7 December 2000 it produced a more acceptable amnesty bill. Even so, President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, formerly Chief Justice on Turkey's high court, vetoed the new bill, believing it unconstitutional. But the TGNA overrode his veto and, under Turkey's constitution, Sezer was required to sign the bill the second time it came to his desk. The legislation thus became law in mid-December.

The amnesty bill was controversial among lawyers and lawmakers, and unpopular with the public. There were at least two reasons for this.

First, an amazing 35,000 inmates--almost half of everyone in Turkey's prisons � would walk free under its provisions. And even this number may be low, some legal scholars believe, since it may reflect an unconstitutional bias in favor of some criminals and against others. President Sezer (or a minimum of 110 TGNA deputies) could ask the Constitutional Court to review the law. If the Court reviews the law and finds it unconstitutional, it could expand this relatively limited amnesty to include tens of thousands more.

Second, many of the criminals slated for freedom were imprisoned for serious, even violent, offenses, like murder. The families of the victims were understandably up in arms. As for the inmates not covered by the amnesty, these included those guilty of crimes against the state, i.e., political crimes. The ones in the latter group, of course, were precisely those leftists who ran the old prison dormitories and were starving themselves to protest the move to F-type prisons. The mix was dicey, to say the least.

Ankara Takes Back the Prisons

|

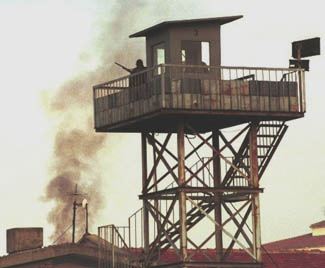

| Smoke rising from Buca prison in Izmir, Turkey on December 19 after a raid by Turkish soldiers [AP/Sukru Akin] |

On the one hand, none of the hunger strikers were dying yet, and the amnesty � which (who knows?) might have partly defused the situation--had not yet been signed by President Sezer. On the other hand, there is rarely a good time for an operation of this sort. Usually there is just a choice of bad ones. This appears to be the situation the Turkish authorities believed they faced--i.e., they had several bad times from which to choose, and they simply picked one.

In any event, once the order was given, government forces concentrated on 20 prisons. Resistance by the prisoners was strong, perhaps unexpectedly so. The Ministry of Interior said prisoners had homemade flame-throwers, Molotov cocktails, and pipe bombs. At Canakkale prison, police had to use heavy machinery to knock holes in the walls to gain entrance.

The fighting lasted four days. It was the worst prison violence Turkey had seen in decades. Thirty prisoners and two policemen were killed. Many of the dead prisoners reportedly set themselves on fire and burned to death.

In the midst of the four-day battle, President Sezer signed the controversial amnesty law, putting its provisions immediately into effect. The first inmates freed were from Buca Prison. As of early January 2001, tens of thousands had walked free, and Ankara was well on the way to achieving its goal of cutting the prison population in half. Stability was finally restored on 22 December with the defeat of 423 inmates at Umraniye prison in Istanbul. On 23 December, Turkish authorities began moving prisoners--starting with the leaders of the leftist gangs--into the new F-type prisons.

Victory and Aftermath

By mid-January the siege had been over for weeks, the transfer to the new F-type institutions was almost complete, and Ankara's authority inside the prisons had been restored after more than a decade of control by radical leftwing gangs. So, by most reasonable measures, the Turkish government had won and the revolutionaries lost. But victory was not cheap.

First, the release of the 35,000 prisoners outraged the Turkish public. Watching these criminals walk free was demoralizing. And it was not just criminals in jail who benefited. In fact, many Turks were especially galled to see rich lawbreakers who had profited from public corruption, and then fled the country to avoid prison, return free and clear to resume their jet-set lifestyles. This ripped at the social fabric, and further undermined the trust people must have in their public institutions if civil society is to be nurtured and grown. Second, the Revolutionary People's Liberation Party-Front (RPLP-F), many members of which were killed during the fighting, vowed revenge and is fully capable of carrying out its threat.4

Third, human rights groups, both inside and outside Turkey, criticized the government for its conduct during the four-day prison battle (excessive force was the common charge) and for brutality and torture during the subsequent transfer of inmates to the new F-type prisons. The government closed five branches of Turkey's Human Rights Association for unauthorized protests, and four people were arrested on 7 January for demonstrating without permission--they had tried to lay a black wreath outside the Istanbul offices of Prime Minister Ecevit's Democratic Left Party.

The first two points (i.e., the prisoner release and the RPLP-F threat) affected public trust and domestic tranquility. They were unwelcome, especially the further weakening of the public's faith in its government, but they were basically internal matters.

The third, however, had international repercussions. Parliaments and mass media in the European Union (EU), a club Turkey very much wishes to join, quickly cited the prison crackdown as an example of human rights abuse by the Turkish government. And, of course, Ankara's subsequent arrest of unauthorized protesters did not help matters.

Some of the EU's indignation was phony. Several European countries--Greece, most obviously--are often looking for excuses to beat Turkey over the head with the human rights stick, whether deserved or not. For these critics, human rights in Turkey is not a genuine issue, but rather a convenient excuse for keeping Turkey out of the EU.

But for many Europeans (and Americans, too), Turkey's human rights situation is an honest concern. Before judging Prime Minister Ecevit and the rest of the Turkish leadership too harshly, however, these observers should consider matters from Ankara's perspective.

The hunger strikers were not well-meaning social democrats, peacefully agitating for progressive change. They were dedicated, violent revolutionaries intent on maintaining their power bases within the prisons. Their aim was victory over the Turkish government, not accommodation with it. When faced with defeat, many set themselves ablaze rather than surrender. Can anyone truly believe that these prisoners would have settled for anything short of total capitulation from Ankara?

And how could Ankara have capitulated? The radical left in Turkey does not play games. During the 1970s, cadres of leftwing extremists--with plenty of help from gangs of rightwing fascists--went on a rampage of political murder and destruction that pushed Turkey to the brink of anarchy. The government simply could not let these same groups, and their political descendants, continue running revolutionary recruitment centers and training camps inside the nation's prisons.

Could Prime Minister Ecevit and the Turkish government have handled the situation differently? Of course they could have. Would the result have been any different? Probably not. The script for this sad drama, including its tragic end, was written by the leftwing thugs who controlled daily life in Turkey's prisons. However regrettable, the government in Ankara did what it had to do.

Notes

1 Pope, Hugh and Nichole. Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey (The Overlook Press, Woodstock and New York, 1998), p. 137.

2 Ibid., p. 136.

3 I am not suggesting that the only reason the amnesty bill was proposed and passed was to clean out the prisons. There were other reasons, too, including Rahsan Ecevit's original desire to give prisoners a second chance. But the need to cut the inmate population was an important factor.

4 For background on the RPLP-F, see the United States Department of State's report Foreign Terrorist Organizations Designations 1999, 8 October 1999. The report can be found at the Department's web site.