|

| Vol. 2 No. 11 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | December 2000 |

| Laurie Mylroie has taught at Harvard University and the U.S. Naval War College. Presently, she is the publisher of Iraq News and the Vice-President of "Information for Democracy." She is the author of Study of Revenge: Saddam Hussein's Unfinished War Against America. |

|

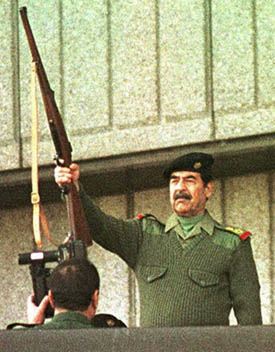

| Iraqi President Saddam Hussein fires a rifle on November 20 to kick off "Al-Quds Day," celebrating Iraq's commitment to liberate Jerusalem [AP/Jassim Mohammed] |

With the Palestinians’ "Al-Aqsa Intifadah," which began in late September, Iraq has adopted an extraordinarily vicious attitude toward Israel. Iraq has done so because its fundamental position is that Israel’s existence in the Middle East is illegitimate.1 But Iraq’s posture also serves to attract the support of the Arab street for Baghdad’s cause of ending sanctions and the other constraints imposed on Iraq during the 1990-91 Gulf Crisis. Iraq’s belligerent position towards Israel also serves to intimidate other Arab governments. At the same time, its enhanced bellicosity is promoting an accelerated rapprochement with Damascus. Consequently, Israeli officials have recently begun to express their concern about the possible formation of an "Eastern Front," involving Syria and Iraq, and for the first time in a decade they are speaking about the possibility of a regional war. That marks a drastic change from the sunny optimism, grounded in the peace process that has dominated Israeli policy in the Middle East for many years.

Baghdad's Renewed Hostility toward Israel

Iraq launched 39 SCUD missiles on Israel during the 1991 Gulf War, but afterwards avoided expressing a very hostile posture toward the Jewish state or conducting terrorist attacks against it. The Israelis soon came to focus their attention on Iran, and, for all practical purposes, forgot about the threat from Iraq.2 Part of the reason for this lay in the peace process and the exaggerated expectations attached to it. The Rabin and Peres governments believed that they could actually achieve peace with secular figures such as Syrian President Hafez Assad and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat. The U.S. victory in the Cold War and the Gulf War, it was said, created a radically new situation in the region. The only elements that really opposed peace with Israel were "irrational"--i.e. religious extremists. Thus, as Itzhak Rabin told a Jerusalem audience a year before his death, "even Syria and Lebanon . . . support peace . . . The enemies of peace are the members of the movements and the organizations that belong to the ugly wave of extremism [and] fanaticism. . . They are the enemies of peace and in their lead is Iran."3

Of course, one of the consequences of that view was to whitewash political figures who were not Islamic extremists, like Assad and Arafat. It also caused many people to forget about Iraq, for similar reasons.4 Even the Likud government of Bibi Netanyahu did not radically challenge the basic assumptions about the Middle East in the 1990’s that the Rabin/Peres governments had introduced.

Iraq spent some years recovering from the Gulf War. It was not until 1997 that Saddam was prepared to take up the rhetorical torch against Israel. In his July 17 national day address that year, Saddam suddenly attacked Jews and Israel in remarkably vile terms. He attributed the Britain’s support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine to the desire to "get rid of the evils and greed of the rancorous Jews" and "drive a wedge in Arab unity." Saddam also called on the Palestinians "to closely monitor and engage the Zionist entity and mobilize Palestinians at home and abroad, . . . . so all can bore into the Zionist body, weaken its power, expose its false and sinister claims, and exhaust it."5

Three years later, that intifadah exists and Iraq has been its foremost supporter. The present Palestinian uprising was precipitated by the September 28 visit of Likud leader Ariel Sharon to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, yet it is clear that the Palestinian Authority (PA) had long been planning for the uprising and used Sharon’s action as a pretext. The possibility even exists that there was some degree of coordination between the PA and Baghdad.

On October 3, Saddam launched a vicious attack on Israel. "An end must be put to Zionism," he asserted. "If they (the other Arab leaders) cannot, then Iraq alone is able to do so. Let them give us a small adjacent piece of land and let them support us from afar only. . . . . We say we can do this today and now. We will not wait until the day comes when the blockade is lifted to put an end to them."6

Arafat sought an Arab summit to support the Palestinians. All attempts to end the Palestinian violence before the summit were in vain (as they were subsequently). In many countries, including Egypt and Jordan, large-scale popular protests took place in support of the Palestinians. Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak decided to call for an Arab summit, which would take the edge off the protests by showing Arab populations that their governments were doing something to aid the Palestinians. The summit was scheduled for later in October.

The Palestinian violence continued and Baghdad kept up its ferocious rhetoric. Indeed, it took even more serious steps. On October 12, a division of Republican Guards was suddenly reported to be moving west out of Baghdad.7 U.S. officials initially dismissed the movement as a training exercise. But ten days later, it was reported that five Iraqi armored divisions were in the west of the country. Four of them had taken up positions on a key crossroad, less than a hundred miles from the Jordanian border, while the fifth, located further north, was less than 100 kilometers from the Syrian border.8

The Iraqi troops--four Republican Guard divisions plus one mechanized infantry division--were among Iraq’s best units. Yet even when it became clear that they were not engaged in training exercises, the Clinton administration dismissed their significance on the grounds that they lacked air cover. Of course, Iraq might have had other ways to deal with that problem. If there were Iraqi coordination with Syria, then perhaps Syria was to provide the air cover, should those troops attack. What Saddam intended was not clear, as the forces were eventually withdrawn without incident. But perhaps Saddam sought to pressure the Jordanian government, as there was substantial unrest in Jordan in support of the Palestinians. Perhaps Saddam also meant to impress Damascus. Despite the sanctions and all that Iraq had experienced over the past decade, it could still be helpful to Damascus in the struggle against Israel. Indeed, Israeli Chief of Staff Shaul Mofaz subsequently explained that "Iraq’s decision to move troops toward the Jordanian border was a sign of the country’s willingness to join a war against Israel, should one break out."9

When the Arab summit convened on October 21, Iraqi forces were still threatening Jordan. The meeting was only the second Arab summit to be held since the Gulf war and it was the first to which Iraq was invited, marking a significant milestone in Baghdad’s regional rehabilitation. Vice-President Izzet Ibrahim al-Duri led the Iraqi delegation. It acted with relative restraint. The Iraqis refrained from attacking other rulers and did not push their own agenda that included ending the no-fly zones and lifting sanctions. Instead, Baghdad adopted the position that the purpose of the summit was to support the Palestinians. But as the summit ended, the Iraqi delegation pronounced that the decisions it had taken were too weak. The Iraqi delegation issued its own statement expressing Baghdad’s "reservations."

The Palestinian-Israeli violence continued and led to an emergency summit of the Islamic Conference Organization, hosted by Qatar, from November 12-14. The ICO summit produced more tangible gains for Baghdad. The small gulf shiekhdom of Qatar has taken a relatively friendly position toward Baghdad. It aspires to mediate between Iraq, on the one hand, and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia on the other. Thus, Qatar’s Foreign Minister explained that "between 70 to 80 per cent" of the summit’s diplomatic efforts were focused on "narrowing the differences" between Iraq and the two Arab states.10 In effect, that meant appeasing Baghdad. Indeed, one paper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine, termed the meeting "Saddam’s Triumph, "observing that Baghdad got more out of the conference than the Palestinians.11

The ICO summit communiqué affirmed the legitimacy of flights to and from Iraq. In mid-August, Iraq had ostentatiously announced the formal opening of its international airport. Subsequently, a host of countries flew "humanitarian" flights to Baghdad. Still, the ICO’s imprimatur was important to Iraq, as were the flights themselves. The most important purpose of the ban on flights to Iraq was to prevent the smuggling of material for Baghdad’s proscribed unconventional weapons programs. Without direct flights, a small risk always existed that any such material could be intercepted en route to Baghdad. That was particularly relevant to the smuggling of the most sensitive material, relevant to Iraq’s nuclear program. All Baghdad needs to produce a nuclear bomb is 35 pounds of highly enriched uranium. With flights to and from Iraq having become commonplace (including flights from Russia), so the possibility that Iraq will be able to acquire such material on the international black market is much enhanced. But such concerns were far from the minds of those at the ICO summit.

The ICO summit also endorsed language demanding "the halt of the illegitimate actions carried out against Iraq." Although the summit communiqué did not further identify what was meant by "illegitimate actions," Iraq and its supporters, understood the language to be an implicit condemnation of U.S. and British enforcement of the no-fly zones and the occasional bombing attacks it entailed.12

The Palestinian violence has thus provided Baghdad the opportunity to make significant advances in the region. And these advances have occurred even as Iraq has continued to berate and challenge other Arab governments. Baghdad maintains that they are hopelessly weak in their support of the Palestinians and they have essentially sold out the Arab cause to the United States. For example, shortly after the ICO summit, Saddam asserted that "there will be no security, no safety, or stability for the Arabs if this entire Zionist entity is not removed." He called on the Arab states that maintained ties with Israel to cut them and condemned those states "blocking the way of the fighters toward Jerusalem."13

One reason that Middle Eastern regimes seek some degree of reconciliation with Baghdad is that they are afraid of Saddam. Soon after Iraqi forces pulled back from the Jordanian border, Jordan’s Prime Minister flew to Baghdad, becoming the first head of government to do so. Saddam is a hero to many of those in opposition to Arab governments. Particularly in periods when regional passions are inflamed, Saddam’s popularity with opposition forces provides him leverage with the governments they oppose. And Iraqi intelligence could become involved with domestic groups that oppose Arab governments that try to thwart Baghdad’s will. It could easily help them carry out more effective anti-government action than they are capable of on their own. This aspect of Iraqi power is, however, rarely noted.14

Conclusion

Among the elements of Iraq’s enhanced status in the region is its developing alignment with Syria. Damascus’ new ruler, Bashar Assad, does not share his father’s personal animosity toward Saddam and relations between Iraq and Syria have warmed considerably since he took power. And Bashar is at least as hostile to Israel as his father. Most notably, following Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon, Damascus has continued to support Hezbollah attacks on Israel, ignored Israeli warnings and even brushed aside a request from the U.S. Secretary of State to restrain the organization.15 Rather, Damascus is doing quite the opposite. It is holding talks with Baghdad about Iraqi military support in the event that Israel retaliates for Hezbollah’s activities.16 And that is causing anxiety in Jerusalem. As one Israeli security source explained, "Bashar is very extreme. He has turned very hard in the direction of the Iraqis." If Israel gets embroiled in a conflict with Damascus, the source warned, Iraq would be delighted to join in."17

The United States and Israel have long turned a blind eye to Saddam’s resurgence. For the most part, the peace process took precedence over all other issues, including Iraq. But now that the consequence of eight years of neglecting the unfinished business of the Gulf War are becoming apparent, even the staunchest advocates of the peace process are beginning to take note.

Notes

1 See Laurie Mylroie, "Why Saddam Hussein Invaded Kuwait," Orbis, Winter 1993.

2 This author knew Itzhak Rabin and many people in his government and sought to explain that Iraq was a much greater danger than they recognized. Repeatedly, the information was accepted at lower levels, only to be rebuffed at higher levels in Jerusalem. As late as July 1999, this author sought to explain to a Barak aide that Israel could not trust the Clinton administration to protect it against Iraq. The aide brushed off the caution, asserting that Clinton was extremely friendly and supportive of Israel.

3 Reuters, November 12, 1994. Although Rabin was more sober than Peres in his evaluation of the "new" Middle East, he, too, was caught up in a version of that vision. For a recent assessment of Rabin’s misjudgments, see Norman Podhoretz, "Death of an Illusion," Commentary, December 2000.

4 There are many instances of this. For example, the Middle East Contemporary Survey (Westview Press) is an annual produced by the scholars of Tel Aviv University’s Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies. In October 1997, shortly after Richard Butler became UNSCOM chairman and issued his first report, this author advised the MECS editor that he (and others writing for him) were not paying enough attention to the danger posed by Iraq and specifically, to the UNSCOM reports. He replied, "What’s an UNSCOM report?" This author had the same exchange with the individual at Tel Aviv University’s Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, responsible for dealing with unconventional weapons threats. When advised that he was not paying enough attention to the UNSCOM reports, he asked, "What’s an UNSCOM report?"

5 Iraq Television, July 17, 1997.

6 Iraq Television, October 3, 2000.

7 Associated Press, October 12, 2000; BBC, October 13.

8 Israel Television, October 22, 2000; Yedi’ot Aharanot, October 25.

9 Jerusalem Post, November 8, 2000.

10 Reuters, November 14, 2000.

11 Frankfurter Allgemeine, November 15, 2000.

12 Al-Sharq al-Awsat, November 15, 2000.

13 Iraq Radio, November 17, 2000; the speech also featured prominently in the Iraqi press the next day.

14 For example, the journalist Mary Anne Weaver visited Upper Egypt after the November 17, 1997, terrorist attack in Luxor. That assault killed more foreign tourists on a single day than had been killed in the previous five years of Islamic terror in Egypt. It dealt a devastating blow to Egypt’s economy. Weaver observed the pictures of Saddam Hussein on the mud-baked walls, but the question never arises whether there is any Iraqi intelligence activity in Upper Egypt. A Portrait of Egypt: A Journey through the World of Militant Islam (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998), pp. 260-276.

15 Jerusalem Post, October 19,2000.

16 New York Times, December 1, 2000.

17 The Independent, December 2, 2000.