|

| Vol. 2 No. 7 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | 5 August 2000 |

In his first televised public address since taking the oath of office as Syria's sixteenth president, Bashar Assad announced to the Syrian people on July 17 that it would be "impossible" for the country to become a Western-style democracy and called for "democracy specific to Syria, that takes its roots from its history, and respects its society." By this point, of course, most Syrians had already come to understand what Bashar was really saying: that political liberalization "specific to Syria" would be limited not by the country's unique culture and society, but by Syria's unique brand of authoritarian government.

|

| Syrians wait in line at the polls, carefully considering their choice for president [SANA] |

The next day, Syrian Interior Minister Muhammad Harba proudly announced that 8.69 million voters said yes, 22,439 voters said no, and 219,000 votes were "invalid" (he did not elaborate).2 The claim that Bashar was approved by 99.7% of the valid ballots cast in the election (or 97.3% of all ballots) was designed to communicate an unmistakable message to the people of Syria and the larger Arab world. For weeks, Syrian political analysts and commentators writing in the London-based Arabic press had speculated that Bashar would signal a break with the past by not claiming to win 99% or more of the vote. "One could imagine what an immediate and dramatic effect on the Syrian public such a leap in the direction of truth--albeit only part-truth--would have had," Syrian analyst Subhi Hadidi solemnly wrote after the results were announced. "One will have to conclude not only that Bashar is the son and creation of the past, but that he has started to drag the past into the present."3

Since his father's death, Bashar has been portrayed by the press as an open-minded, Western-educated, internet-savvy reformer, poised to tear down the walls of one of the most isolated, economically backward, authoritarian states in the world. Notwithstanding the fierce criticism of Hadidi and others, Bashar may well have precisely these intentions, but bringing about reforms while operating within an autocratic political system is a complicated task. At every step along the path toward political and economic liberalization, the necessity of ensuring his regime's survival will trump all other considerations.

This has been particularly evident in Bashar's so-called "anti-corruption" campaign. He cannot escape the confines of Syria's authoritarian system simply by replacing members of the "Old Guard" with reform-minded technocrats, for this would risk the downfall of the system itself. In order to square this circle, Bashar has had to leave some members of the Old Guard in place, while gradually shifting real power, not to technocrats, but to a "New Guard" of military officers who are competent enough (and ruthless enough) to make sure that the system prevails long enough to be reformed. Since Bashar himself has so little experience running the system, members of the New Guard have been given a great deal of autonomy.

|

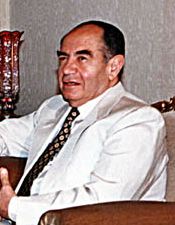

| Hikmat Shehabi |

However, according to informed sources, Bashar had nothing to do with Shihabi's departure in the first place. The entire scheme to facilitate Shihabi's exit by making the leaks to Al-Hayat was undertaken independently by Bahjat Suleiman, the head of internal affairs at the General Security Directorate and one of Bashar's closest advisors. Suleiman, like many other members of the minority Alawite establishment, apparently feared that Shihabi (a Sunni Muslim) might cause trouble after the Syrian president's death. In any case, a source close to former Lebanese prime minister Rafiq Hariri (a close friend of Shihabi who saw him off at the airport) told MEIB that Bashar discovered the plot and phoned Hariri to explain, but by then the plane had already taken off. Only after repeated assurances during the next month did Shihabi agree to return.

Whether Bashar is fully in control of the regime is, of course, difficult to determine with certainty, but it is clear that his security chiefs exercise much more autonomy and independent initiative than their counterparts did under the late Hafez Assad and that their primary concern is the preservation of the regime. Bashar's desire to reform the system from within will continually be held in check by their risk assessments.

The style and pace of economic reform are subject to similar considerations. For example, the announcement last month that a consortium of Syrian and Saudi investors had received approval to build a $40 million dollar five-star hotel in the country seems like welcome news, but it is being built in a predominantly Alawite area of the Latakia province--the laborers who are hired to build it will be predominantly Alawite, the appreciation in real estate prices will benefit Alawite landowners, and revenue generated from increased tourism in the area will mainly enrich Alawite businessmen.

All other things being equal, the flow of private investment into the country will be channeled in ways that shore up the regime, rather than benefit the population at large. The decision last month to allow Lebanese banks to open branches in Syria reflects the same prerogative--the regime's continuing military and political control over capital-rich Lebanon (which has $30 billion in bank deposits, compared to $5.5 billion in Syria), will allow it to control who these banks lend their money to.

The July 7 decree by Prime Minister Muhammad Mustafa Miru lifting the 30-year ban on private automobile imports is another small step toward a more open economy, but the limitations are revealing. Foreign companies are still not allowed to directly enter the Syrian market, but must contract with local agents (who, no doubt, will be close to the regime). The law also excludes diesel-powered vehicles and used cars that are over two years old, the sale of which will continue to be monopolized by a state agency.5

Just as the state-centered economy of the late president Assad was geared to benefit the Alawite community in general and a select strata of commercial elites in particular, the benefits of Bashar's limited drive toward economic liberalization are likely to accrue disproportionately to the same constituents.

1 Al-Quds al-Arabi (London), 3 August 2000.

2 Al-Safir (Beirut), 12 July 2000.

3 Al-Quds al-Arabi (London), 25 July 2000. Translation by Mideast Mirror.

4 Al-Hayat (London), 6 June 2000.

5 Al-Hayat (London), 8 July 2000.