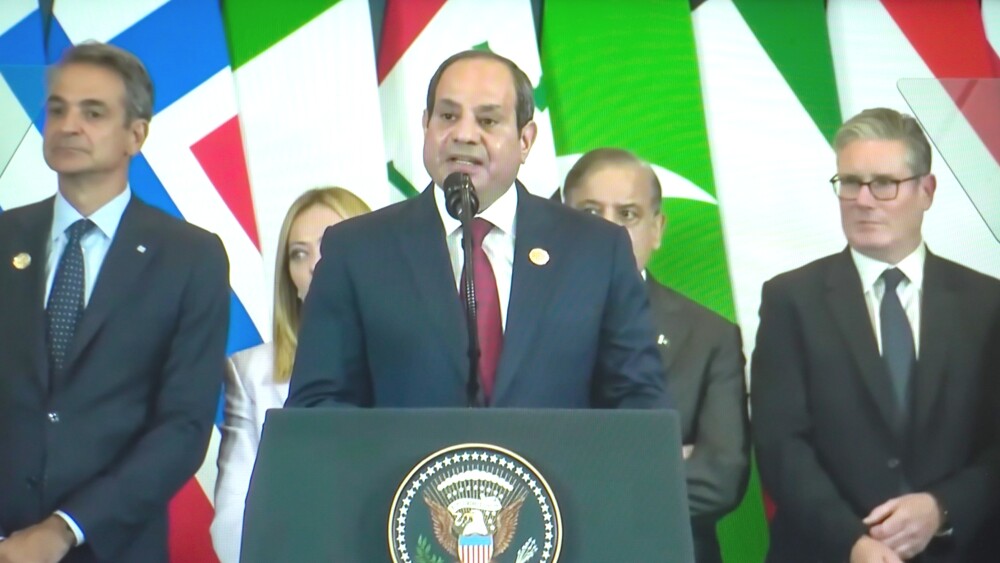

On October 20, three official reports emerged from Egypt’s state and religious media apparatus, detailing a coordinated architecture of religious and state policy. Another report appeared a week earlier. Taken together, these four announcements—driven by President Abdel Fattah el Sisi, his Minister of Awqaf (Endowments), Sheikh Al-Azhar, and the Mufti of the Republic—reveal a systematic effort to expand Sunni-Muslim influence across education, culture, youth programs, and state asset management. Cloaked in the language of “moderation” and “national cohesion,” their real agenda is more dramatic: the religionization—that is, Islamization—of the Egyptian state, with profound consequences for Egypt’s minorities, first and foremost, its most ancient community: the Coptic Christians.

The four recent initiatives follow:

1. Sisi and Awqaf: Expansion of imam and preacher training, nationwide children’s programming in 20,000-plus mosques under the banner “Correct Your Concepts,” and directives to maximize financial benefit from Awqaf endowments.

2. Culture Ministry and Dar al-Ifta: Joint publications, training programs, and cultural outreach aimed at “building the Egyptian human” via state-approved “moderate thought.”

3. Dar al-Ifta and the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM): Civilizational heritage is being closely tied to religious messaging, further embedding Islam into the narrative of national history and tourism.

4. Al-Azhar and Cairo University: Curricula and research explicitly drawing on Islamic heritage to “respond to contemporary challenges.”

Such developments are not new or unique. In the past few months alone we have seen the Minister of Awqaf meeting the Minister of Education, the head of the Space Agency, the Mufti meeting the Foreign Minister, and reports on promoting Kuttab (Quranic madrassah, not unlike those of Pakistan, or Afghanistan.) These are all are part of a growing and persistent pattern.

Nor are these isolated policy tweaks; they form a deliberate, multi-institutional strategy to weave Islam into the fabric of Egyptian life—into schools, mosques, universities, museums, youth programs, and cultural centers. The projected outcomes are clear: a regime bolstered by religious legitimacy, and a narrowing of civic space for non-Muslim voices.

The projected outcomes are clear: a regime bolstered by religious legitimacy, and a narrowing of civic space for non-Muslim voices.

The power dynamics are likewise evident. Sisi commands the overarching program; the Ministry of Awqaf supplies infrastructure and finances; Al-Azhar and Dar al-Ifta provide religious legitimacy, training, and doctrinal authority.

That children are targeted in over 20,000 mosques reveals how early the indoctrination begin. The push to extract maximum value from Awqaf assets shows how financial levers are being mobilized to fuel the religionization project.

The rhetoric of “moderation,” “national identity,” “combating extremism”, functions as a legitimizing veil. Beneath it lies a more sinister reality: the state is embedding a particular religious worldview—a distinctly Islamic one, aligned with government priorities—into the everyday life of Egyptians. Religious institutions are now openly no longer independent moral actors—they are conduits of state ideology.

For Egypt’s Coptic Christians, who make up 10–15% of the population, the consequences are dire. High-profile state visits and symbolic gestures cannot counterbalance a policy that systematically sidelines them:

Institutional Marginalization: As Sunni-Muslim institutions dominate identity formation, Coptic institutions have no equivalent role. Museums, curricula, and mosque programs are Sunni-controlled; Christians are relegated to being passive observers, even more excluded from nation-building than they were before.

- Civic and Legal Risk: Copts continue to face unequal treatment under personal-status laws, church construction restrictions, and sectarian violence. U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom reports note that courts are applying Sharia inheritance rules to Christians in violation of their faith.

- Narrative Control: Linking “national identity” to state-sanctioned Islamic heritage implicitly erases millennia of Egypt’s pre-Islamic history, from the Pharaohs to the Copts. The ancient role of Coptic Christians in Egypt’s national story is actively canceled.

- Content Exclusion: Museum programs and curricula framed around Sunni-Islamic narratives systematically erase minority histories, weakening both visibility and identity.

- Symbolism vs. Substance: While church-building initiatives and state visits are touted, real influence over socialization sites—mosques, universities, cultural programs—is firmly in Sunni-Muslim hands.

Nor does the term “moderate thought” offer any reassurance. It signals only to state-approved Islam. Voices outside this official line—Christian minorities, independent Muslims, critical religious actors—are delegitimized. The joint cultural programs are designed to create a citizenry whose moral compass is centrally managed and Muslim-oriented.

Meanwhile, the state reaps enormous benefits:

- Consolidating Sisi’s legitimacy by presenting him as guardian of both state and religion—a modern sultan, if not a caliph.

- Embedding state-approved religious norms into social infrastructure, ensuring generational compliance.

- Leveraging Awqaf’s financial and symbolic network to extend government influence deeper into society.

What to watch for:

Content of children’s mosque programs: presentation of minorities, civic values, and the shaping of historical memory.

- Composition of imam and daʿwah training: curriculum control and enforcement of ideological orthodoxy.

- Allocation of Awqaf revenues: exclusive Sunni-Muslim programs or genuine interfaith initiatives.

- Representation of Coptic heritage in museums, curricula, and cultural forums.

- Implementation of legal reforms promised to minorities versus expansion of religion-state infrastructure.

What these announcements reveal is more than a “reform” agenda—moderate or otherwise; they signal the emergence of a new civic-religious order in Egypt. Sunni-Muslim institutions are being harnessed to mold national identity, manage youth, and consolidate power.

Within this architecture, the already marginalized Copts are set to see their long-standing vulnerability deepen.

Published originally on October 22, 2025, under the title “Egypt’s Coordinated Islamization Program—and What It Means for Coptic Christians.” Text may differ slightly from publisher’s.