|

| Vol. 5 No. 7 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page |

July 2003 |

|

|

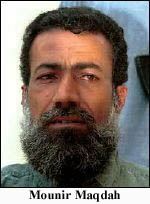

Dossier: Mounir al-Maqdah former Fatah commander |

|

Background

Mounir al-Maqdah was born in 1960 in the Palestinian refugee camp of Ain al-Hilweh, on the outskirts of the Lebanese port of Sidon, the son of Palestinians who fled the village of Al-Ghabissiyeh in Galilee after the 1948 establishment of Israel. At the age of ten, he left school to join the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which then had an extensive military and political presence in Lebanon. After initially joining the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) and training in Syria, he switched over to Yasser Arafat's Fatah movement. Over the next decade, he rose to become a respected commander in Arafat's elite Force 17 unit.

During the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, Maqdah commanded Fatah forces defending Ain al-Hilweh. Although his unit was defeated, he is said to have displayed courage in the face of overwhelming adversity that contrasted sharply with the cowardice and corruption of senior PLO field commanders. When the PLO was expelled from Beirut in the fall of 1982, Maqdah initially went with Arafat to Tunis, but returned to Lebanon a few years later. He continued to distinguish himself as a field commander in the years that followed, as Fatah forces in Lebanon were driven to the South from Beirut and north Lebanon by Syrian-backed Palestinian militias.

When the Syrian-backed Lebanese army mounted an offensive to seize Fatah's last major strongholds in south Lebanon in July 1991, Maqdah again distinguished himself in the defense of Ain al-Hilweh. Although Fatah forces were forced to surrender most positions beyond the perimeter of the camp, their fierce resistance persuaded the Lebanese army not to push into Ain al-Hilweh itself.

Tensions with Tunis

Relations between Maqdah and the PLO leadership in Tunis deteriorated in the early 1990s. Arafat's alignment with Iraq during the 1990-91 Gulf crisis had prompted oil-rich Arab states to halt their financial aid to the PLO, forcing it to reduce the salaries of Fatah fighters in Lebanon and severely cut its funding of social welfare institutions in the camps. Resentment against Arafat was furthered fueled by widespread expectations that the Palestinian-Israeli peace talks that began in Madrid in 1991 would not alleviate the suffering in Ain al-Hilweh, where 90% of the residents are descendants of people who fled to Lebanon in 1948 from areas that became part of the state of Israel.

Following Arafat's decision to participate in the 1991 Madrid peace conference, Maqdah and 300 of his armed men launched a bloodless coup in Ain al-Hilweh, reportedly after meeting with leaders of Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed militant groups. Although he returned to the fold after forcing Arafat to appoint him commander of all Fatah forces in Ain al-Hilweh, the coup underscored that Maqdah, not the PLO leadership in Tunis, was in control.

By the spring of 1993, the financially bankrupt PLO had stopped paying the salaries of Fatah fighters in Lebanon entirely and the camp was on the verge of mutiny. In August, Maqdah openly called on Arafat to resign. "For how much longer can Arafat continue to watch the destruction of our institutions ... as thousands of Fatah officers go begging in Arab capitals?" Maqdah told Agence France Presse. "It's time for Abu Ammar [Arafat's nom de guerre] to resign."[1]

Despite widespread anger in Ain al-Hilweh over the PLO's neglect of the camp, pro-Syrian Palestinian factions were unable to gain ascendancy - memories of atrocities by the Abu Nidal Organization in 1990-1991 were far to fresh to allow for this. However, while Maqdah himself had fought Syria tooth and nail during the 1980s, he now began to openly ruminate about aligning with Damascus:

We fought the Syrians 15 years to protect our independent decision-making and escape hegemony. Where's the independent decision? Is it with the Egyptian regime? Instead of going through Egypt, why don't we go through Syria? In Egypt we say our capital is Gaza, but in Damascus we say the capital of the Palestinian state is Jerusalem.[2]

After the signing of the September 1993 Oslo Accords, Maqdah grew even more defiant, telling a Reuters correspondent, "We will not lay down our weapons until complete liberation . . . Sooner or later we will throw the Zionists into the sea."[3]

On October 14, the PLO leadership in Tunis officially fired Maqdah as commander of Fatah forces in Lebanon, naming a new command council to be headed by Lt.-Col. Badih Kurayem and include Majors Maher Shbatieh, Khaled Shayeb and Mansour Azzam. However, Shayeb and Azzam refused to accept their posts and joined Maqdah, who announced the creation of the Black September 13 Brigades [kata'ib al-thalith ashar min aylul al-aswad], named after the date of the PLO-Israeli accord. Under pressure, Shbatieh and Kurayem switched sides as well. Within a few weeks, more than 20 of the top 32 Fatah political and military officials in Ain al-Hilweh had rallied to Maqdah's group (which appropriate the same insignia, logos, and charter of Fatah) and all but a few Fatah posts in the camp were under his control. Arafat retained control only of one major post at the eastern end of the camp, commanded by Kamal Medhat, the head of Fatah's intelligence service in Lebanon. Arafat's influence in Lebanon was now confined mainly to Rashidieh, a refugee camp in Tyre, just north of the Israeli border, where Sultan Abu al-Aynayn is commander.

By November, Black September 13 had carried out the murder of a Jewish settler and a few Katyusha rocket attacks on northern Israel. After Arafat's triumphant visit to Gaza in 1994, Maqdah appeared live on CNN and called for his execution.

Into the Arms of Iran

Maqdah repeatedly boasted that he accepted no outside funds. "Our officers work as taxi drivers, as laborers and we have not begged for money from Arafat or any other organization or country."[4] In fact, at some point in 1993, he began receiving funding from Iran to pay the salaries of his commanders, causing loyalty to Arafat in the camp to dissipate entirely.[5] Maqdah also developed close ties with Iranian-backed groups in Lebanon, chiefly Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad.

His relations with Syria also improved suddenly. In November 1994, loyalist Fatah forces led by Medhat launched a surprise attack against Maqdah's supporters, seizing six dissident positions in the camp. In 18-hour clashes that left 10 people dead and 25 wounded, the pro-Syrian Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC) and Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) intervened to help Maqdah recapture three of the positions. His reliance on pro-Syrian factions in the counterattack underscored that there were limits to what Maqdah could ask of his own men. In June 1995, clashes again erupted between the two sides, leaving six dead and 30 wounded in two days of fighting. This time, Arafat's supporters were forced to give up all of their checkpoints near the entrance to the camp.

|

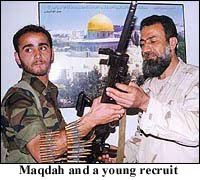

Maqdah's recruits fought Israel on multiple fronts. During the latter half of the 1990s, his commandos launched periodic assaults on Israeli positions in south Lebanon - with a level of sophistication and planning that indicated significant logistical assistance from Hezbollah. In addition, Israeli security forces discovered that some Hamas and Islamic Jihad suicide bombers were being recruited from Maqdah's militia.[7] In April 1996, he narrowly escaped death when Israeli helicopters fired missiles into his headquarters.

In the late 1990s, Maqdah allowed al-Qaeda to begin funding a network of obscure Sunni Islamist groups, most notably Esbat al-Ansar. Maqdah not only allowed Islamist cells to operate freely in the camp, but actively assisted them. In March 2000, he was indicted by Jordan's State Security Court on charges of providing arms and explosives to members of an al-Qaeda cell who planned to carry out terrorist attacks in the Kingdom at the turn of the millennium. Maqdah denied the charges, but said in an interview that he would be "honored to coordinate" with Osama bin Laden if the al-Qaeda leader ever attempted "to liberate the holy city of Jerusalem."[8] In September, he was convicted in absentia and sentenced to death. Since then, persistent Jordanian requests for his extradition have been rejected by Damascus.

The Refugee Card

As the Israeli-Palestinian peace process inched closer to final status talks, Arafat began to appreciate the importance of controlling Ain al-Hilweh - as long as Maqdah's defiance continued, he could not claim to be negotiating on behalf of the Palestinian Diaspora in Lebanon. In 1998, the PA began pouring funds into the camp, drawing some dissident Fatah commanders back into the fold and alleviating economic conditions. Maqdah reconciled with Arafat and rejoined Fatah, but this was largely a symbolic change.

Damascus also coveted the refugee card. While Arafat was telling the Israelis that he would rein in Palestinian militants in Lebanon in return for concessions, the Syrians were telling the Israelis that only they could prevent Palestinian (and Hezbollah) guerrillas from launching raids against Israeli forces from Lebanese soil. As Israel prepared to withdraw from south Lebanon in the spring of 2000, Lebanese President Emile Lahoud sent a memorandum to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, warning that his government could not prevent the "possibility of mini-wars on the border, launched by armed Palestinian groups originating from the Palestinian camps inside Lebanon."[9] The very next day, Maqdah took his cue and proclaimed in an interview that "tens of volunteers from all Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon have come for training and attacks on Israel."[10] PA officials bitterly accused him of acting on behalf of Syria.

The Al-Aqsa Intifadah

Since the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifadah in September 2000, Maqdah has been involved in recruiting, training, funding, and directing at least two semi-autonomous terror networks in the West Bank, both of which are loosely part of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades: Kata'ib al-Awda (the Battalions of Return), based in Nablus, Jenin, and Tulkarm, and Al-Nathir (the Harbinger). The Return Brigades have taken credit for several major attacks, such as a February 19, 2002, ambush that killed six IDF soldiers and the February 27, 2002 murder of an Israeli in the Atarot industrial zone of Jerusalem.[11] In August 2002, the network attempted to assassinate a PA intelligence chief in Tubas.[12] Al-Nathir was reportedly responsible for a July 2002 suicide bombing in Tel Aviv that killed five people. In September 2001, Israeli police arrested a four-man hit squad in the West Bank that had been assigned by Maqdah to assassinate Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon outside his home in East Jerusalem.[13]

Maqdah's connection to the two networks first came to light in 2002 during the interrogation of a Fatah gunman apprehended by Israeli forces, who said he received over $ 40,000 from Maqdah for weapons and bomb-making materials. Israel later tracked the money from a bank in Lebanon to one in Nablus. Another detainee was found to have received an average of $5,000 per week from Maqdah.[14] In mid-2002, the PA launched a major investigation after it discovered that local Fatah commanders had received tens of thousands of dollars from Maqdah.[15] One Fatah official warned that soon there could be "a new generation of Fatah fighters who receive their instructions from Damascus and Teheran." [16]

Maqdah's supporters in the West Bank rejected the recent Israeli-Palestinian cease-fire and have claimed responsibility for several shootings since it came into effect. On June 30, a Bulgarian construction worker (apparently mistaken for an Israeli) was killed in the West Bank. "No one consulted us about this truce," said Maqdah in a recent interview. "We have said very clearly that we will never put down our arms while there is occupation and if one Palestinian prisoner remains in an Israeli jail."[17]

Both Israel and the PA have had difficulty eliminating terror networks connected to Maqdah, who relies upon email and mobile phones to communicate with cells and usually procures and transfers money using the Internet. In an effort to prevent further attacks, the PA has reportedly begun paying Al-Aqsa Brigade commanders with links to Maqdah to observe the cease-fire. "They are human beings. They need to pay the rent and the telephone bill," said one PA minister who confirmed the payments.[18]

If Maqdah is willing to suspend his war against Israel for the right price, however, it is clear that the PA has not been willing to pay it. Part of the reason for this is that Maqdah is on so many other payrolls that he cannot be reliably expected to abide by Arafat's authority at any price. Moreover, he has become a liability since the beginning of the war in Iraq, when the Palestinian weekly Assennara quoted him as saying that "hundreds" of volunteer Palestinian fighters in Ain al-Hilweh had been sent to Iraq to carry out suicide bombings against coalition forces. "Resisting the American aggression on Iraq supports the Palestinian people and the intifadah," said the renegade Fatah commander. "What is happening in Iraq is the battle of the Palestinian people first and the Arab and Muslim nation second."[19] Maqdah later denied that he himself had dispatched the terrorists, claimed that they had traveled to Iraq on their own. However, he acknowledged that he had encouraged Palestinians in the camps to fight in Iraq. "We wish we are all in Iraq fighting the Americans" he said. "Why fight Israel, when you can go and fight their boss [the Americans] in Iraq."[20]

After the outbreak of intense clashes between Fatah forces and al-Qaeda-backed militants in Ain al-Hilweh in May, Arafat reportedly ordered Fatah commanders in the camp to wipe out the Islamists. Maqdah refused to sanction the campaign, however, and it was soon abandoned. This appears to have been the final straw. On June 25, Arafat formally removed Maqdah from his post, ordered him to hand over several strategic checkpoints to Arafat loyalists, and transferred around 150 men under his command to other units. Since then, Maqdah has declined to comment on whether he is still in control of Fatah forces in the camp, while Arafat appears content not to press the issue. For the time being, though, Maqdah's war against Israel continues.

Notes

[1] "PLO military official calls for Arafat to resign," Agence France Presse, 23 August 2003.

[2] Mideast Mirror, 24 August 1993.

[3] Reuters, 8 October 1993.

[4] The Jerusalem Report, 18 November 1993.

[5] "Iran Aids Foes of PLO," The New York Times, 15 June 1994.

[6] "New generation of Palestinians train as 'human bombs'" Agence France Presse, 16 April 1995.

[7] "Where Terror Lurks," The Jerusalem Post, 8 August 1997.

[8] United Press International, 29 March 2000.

[9] Al-Quds al-Arabi (London), 7 April 2000.

[10] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), 8 April 2000.

[11] Agence France Presse, 19 February 2002; Agence France Presse, 27 February 2002.

[12] "New Fatah groups controlled by PLO dissident in Lebanon," The Jerusalem Post, 26 August 2002.

[13]

The four assassins, Mustafa Hassan Abdel-Kader, Youssef Sharif, Khaled Ibrahim and Mustafa Nimr, planned to kill Sharon with a sniper's rifle from the window of Nimr's house, which is near Sharon's residence. Maqdah reportedly provided the team with $5,000 and promised to provide additional funds and weapons. See Yediot Ahronot, 5 November 2001.

[14] "New Fatah groups controlled by PLO dissident in Lebanon," The Jerusalem Post, 26 August 2002.

[15] "New Fatah groups controlled by PLO dissident in Lebanon," The Jerusalem Post, 26 August 2002.

[16] "New Fatah groups controlled by PLO dissident in Lebanon," The Jerusalem Post, 26 August 2002.

[17] The Daily Star (Beirut), 4 July 2003.

[18] "Renegade Palestinians Threaten New Attacks," The Independent (London), 18 July 2003.

[19] The Jerusalem Post, 30 March 2003.

[20] The Daily Star (Beirut), 31 March 2003.

� 2003 Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. All rights reserved.