|

| Vol. 3 No. 10 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | October 2001 |

As overt opposition to Syrian hegemony has spread throughout the sectarian and ideological spectrum in Lebanon in recent years, Damascus and its leading supporters within the Lebanese regime have sought to undermine the secular nationalist movement by co-opting Christian political and religious institutions. Syrian officials have been continuously engaged in back channel negotiations with the Maronite Christian church, the heads of prominent families and former militia elites, hoping to forge a credible coalition of Christian leaders willing to abandon demands for a Syrian withdrawal in return for the protection of Christian political privileges and cultural autonomy.

|

In recent months, this polarization has generated internal struggles deep within the ranks of two once powerful Christian political institutions - the Phalange (Kata'ib) party and the banned Lebanese Forces (LF) party. Within each of these groups, political elites backed by President Emile Lahoud and the staunchly pro-Syrian military-security establishment have launched a concerted drive to seize control and sideline those who remain committed to bringing about a Syrian withdrawal. In conjunction with the massive arrest campaign launched in August against the Free National Current (FNC) and anti-Syrian wing of the LF, the hostile takeover of the Phalange and reincarnation of the LF are designed to deprive the Christian community of any viable institutional channels of political expression apart from those approved by Damascus.

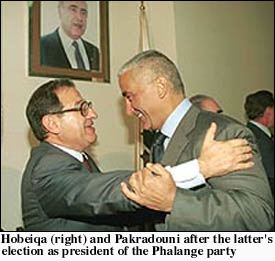

This article examines the transformation of the Phalange and the rise of Karim Pakradouni, who was elected president of the party on October 4. The regime-sponsored "new" Lebanese Forces, to be headed by former LF militia commander Elie Hobeiqa and/or Fouad Malek, will be profiled in an upcoming issue of Middle East Intelligence Bulletin.Background

The Phalange party was first established as a Christian nationalist youth movement in 1936 by Pierre Gemayel, a pharmacist and scion of a prominent family in the town of Bikfayya, north of Beirut, along with such figures as George Nackashe, Charles Helou (a future president of Lebanon, from 1964-1970), Shafic Nassif and Emil Yared. During the final years of the French mandate, the movement frequently drew hundreds of demonstrators into the streets and clashed with rival groups opposed to an independent Lebanese state. Unlike the National Bloc of Emile Edde, the Phalange opposed both French and Syrian control over Lebanon and cooperated with like-minded non-Christian groups, such as the Sunni al-Najjadah movement.

After Lebanon became independent in 1943, the Phalange evolved from a populist youth group into a formal political party. Unlike the largely clan-based political factions prevalent in Lebanon at the time, the Phalange established a broad support base among the Maronite Christian population and developed an extensive hierarchy and bureaucracy.

While the party's membership was almost exclusively Christian (and predominantly Maronite Christian), its ideology embraced the multi-confessional demography of the newly-independent Lebanese state and promoted the notion of a distinctly Lebanese people descended from the ancient Phoenicians. As Arab nationalism spread throughout the region in the 1950s and 1960s, Gemayel and other leaders of the party adamantly maintained that Lebanon had a unique national identity.1

Despite its ostensibly secular nationalist ideology and opposition to political clientalism, however, the party steadfastly defended Christian political privileges embodied in the Lebanese constitution and the 1943 National Pact. Unable to negotiate a revision of the Lebanese political system, Lebanese Muslim leaders moved into an alliance with armed Palestinian groups operating in the country during the early 1970s. Concerned by the Lebanese government's inability to restrain the increasingly assertive Palestinian military presence in Lebanon, the Phalange and other Christian political groups formed armed militias.

Following the outbreak of civil war in 1975, Phalangist military forces commanded by Gemayel's son, Bashir, battled Lebanese Muslim-Palestinian forces, prompting Syrian forces to enter the country the following year. While his father remained nominally the party's head, Bashir emerged as the de facto leader of the Phalange. During the late 1970s, Bashir created the Lebanese Forces, which gradually assimilated his own militia and forcibly incorporated most of the other Christian factions, as a means of centralizing his authority over the Maronite enclave.

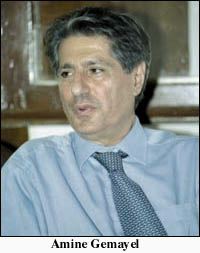

In 1982, Israeli forces invaded Lebanon and occupied Beirut. Swiftly recognizing this new political reality, a broad coalition of Lebanese political elites elected Bashir Gemayel president in August. Shortly thereafter, however, Gemayel was assassinated and his brother, Amine, assumed the presidency.

Pierre Gemayel remained at the helm of the Phalange until his death in 1984. After that, opponents of Gemayel took control of the party (inspired, in part, by President Gemayel's reluctance to distribute civil service jobs to his political supporters). Under the leadership of Elie Karameh (1984-1986) and George Saade (1986-1998), the party moderated its stance toward Syria. Aiming to position itself as the predominant institutionalized expression of Christian political interests, Saade endorsed the 1989 Ta'if Accord, which established the Second Lebanese Republic and provided a legal justification for the presence of Syrian military forces in most of the country. However, a dissident wing of the party remained firmly opposed to the Syrian presence, while Amine Gemayel went into exile and expressed his opposition from abroad.

The Power Struggle in the Phalange

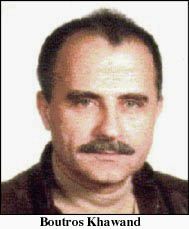

After Syria completed its conquest of Lebanon in 1990, divisions within the party widened, particularly after Damascus reneged on its promise to redeploy its forces out of Beirut by 1992. The opposition faction of the party remained powerful enough to prevent Saade from cutting a deal with the Syrian-installed regime. One prominent figure in the opposition camp was Boutros Khawand, a member of the party's politburo who worked tirelessly to mobilize grassroots activism against the Syrian occupation.

|

Khawand's abduction had the intended effect of scaring the daylights out of other opposition leaders in the Phalange and securing the position of Saade. But even the accomodationist faction of the party found itself unable to justify fully supporting the regime.

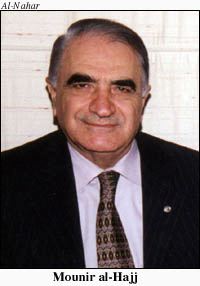

When the party failed to win election for any of its candidates in the 1996 elections, this began to change, particularly after the 1998 presidential "election," which brought to power Gen. Emile Lahoud, a former army commander who began his tenure with considerable Christian support. In March 1999, following Saade's death the previous year, Mounir al-Hajj was elected president of the Phalange and launched full-fledged effort to align himself with the Syrians.

During last year's parliamentary election campaign, Hajj was invited by the pro-Syrian interior minister, Michel Murr, to join his electoral slate in the Metn district. This outraged many rank and file members of the Phalange, who objected to Hajj's association with Murr, and even more so to the fact that Murr's slate included a candidate from the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). The SSNP, which advocates Syrian annexation of Lebanon, once fielded a militia that battled Phalangist forces in Lebanon during the war. Moreover, the late President-elect Bashir Gemayel was assassinated by a member of the SSNP.

|

However, while the combined impact of Murr's powerful patronage network and intimidation by the security forces yielded victory to most of the candidates on his slate, Hajj failed to win a seat in the election. This was due in part to the fact that Amine Gemayel's son, Pierre, entered the race in the final days of the campaign and drew the support of most Phalange supporters in the district. In addition, many of those who voted for Murr's list crossed off Hajj's name from their ballot and wrote in those of rival candidates.

Hajj was deeply humiliated by the fiasco and never recovered politically. As most members of the Phalange party's 25-member politburo began pushing for his resignation, Hajj retained unqualified support from two: Nader Sukkar, who has strong ties to Syria, and George Qassis, who has a deep grudge against Gemayel. Two dissident factions within the party began vying for control.

The first was centered around Amine Gemayel, who returned to Lebanon in late July 2000 after 12 years of exile. Gemayel had received permission to return from Damascus after lengthy negotiations through intermediaries and initially observed the "red lines" imposed by the Syrians on Lebanese politicians. This did not stop him from contesting Hajj's leadership of the party which he considered his birthright. Hajj, for his part, blamed the Gemayel family for undermining his parliamentary campaign.

The second major figure who rose to challenge Hajj's leadership was the party's first vice-president, Karim Pakradouni, an Armenian Christian attorney who was a close advisor to Gemayel during the 1980s. Pakradouni, 57, had been a leading figure in the party since 1968, when he became head of its student wing. He was elected to the party's political bureau in 1970 and thereafter remained in the party's top echelon, leading the so-called "Arabist" faction of the Phalange which favored close ties with Syria. During the 1980's, he was a leading figure in the Lebanese Forces.

|

However, over the course of the following year Pakradouni began to turn against his former boss, complaining that Gemayel would promote his family's parochial political interests at the expense of the country. "The Phalange party is not a monopoly for any one person, family or religion," Pakradouni told reporters in July 2001. "We need to organize the party's internal structure whereby its existence does not depend on a single person but on national destiny."4 Strangely, Pakradouni now felt that a seasoned politician with a strong network of political support at the helm of the Phalange would not be in the interests of the Christian community.

Pakradouni also began to adopt radically pro-Syrian positions on a wide range of issues. During the August crackdown, he wrote an article in Al-Sharq al-Awsat entitled "What Is Happening in Lebanon: Is There a Secret Scenario?" in which he accused former Prime Minister Michel Aoun's Free National Current of collaborating with Israel - an absurd accusation that even the movement's strongest critics deny. In another article, Pakradouni wrote that Christian opposition to President Lahoud is "related directly or indirectly to American and Israeli pressure" on the Lebanese regime, a conspiratorial view that parrots Syrian propaganda.5

Pakradouni's bizarre turnabout stemmed from several factors. First, Damascus and the Lebanese military-security establishment had lost confidence in Hajj and feared that a continuation of Hajj's tenure would drive other politburo members into Gemayel's camp. Indeed, shortly after Hajj's electoral defeat, Pakradouni acknowledged this. "The truth is, they [the authorities] don't care about Hajj . . . what concerns them is Gemayel and how to contain him."6 Pakradouni, who like most other Lebanese political elites has shifted alliances many times over the course of his political career, seized the opportunity.

The second factor was blackmail by the military-security establishment. In 1999, Lebanon's military tribunal filed charges against Pakradouni for allegedly meeting with Israeli officials, a serious crime under Lebanese law. For two year, however, the case has remained in a strange limbo (the military courts normally produce verdicts very quickly), hanging over Pakradouni's head. The desire to escape prosecution on collaboration charges, which have landed thousands of Lebanese in jail over the last decade, has proven to be a powerful incentive to cooperate with Damascus.

Another case used by the regime to blackmail Pakradouni dates back to 1987, when he and fellow Lebanese Forces commander Fouad Malek presided over an ad hoc tribunal of two men suspected of plotting to assassinate Pakradouni. Both men were executed. In recent years, the authorities have threatened to indict Pakradouni for the killing. Although a 1991 general amnesty covers crimes committed during the civil war, the authorities have previously exempted opponents of the Syrian occupation, most notably former Lebanese Forces chief Samir Geagea, who is currently serving multiple life sentences for ordering assassinations.

|

After the regime's crackdown on opponents of the Syrian occupation in August, Pakradouni and Hajj held intensive meetings, fearing that the excesses by the military-security establishment would bolster support for Gemayel within the party. On August 27, they called a politburo meeting to approve moving the date of the party's elections forward from March 2002 to October 4. Oddly, the resolution stipulated that Hajj would still serve out his term as president until April 2002, indicating that its purpose was not to hasten the turnover of power, but to minimize Gemayel's chances of mobilizing support for his candidacy. Gemayel's supporters boycotted the meeting, but Hajj and Pakradouni barely managed to secure a quorum and 13 of the party's 25 politburo members voted to approve the decision.

Gemayel immediately condemned the measure, which he said constituted a "conspiracy to end the role of the Phalange" in Lebanese politics, and angrily announced that he would boycott the elections. The party's second vice-president, Rashad Salameh, adamantly defended the legality of the decision, but alluded to state interference. "I am not saying that there is interference in the party's affairs," Salameh said cautiously, "but at the same time I am not denying the possibility of such interference."7

The party's procedure for electing its politburo is rather complex. The Phalange congress (al-Hay'a al-Nakhiba) elects 20 of the politburo members. The congress consists of both appointed and elected members. The first group is comprised of the current politburo members and appointed representatives of various local branches of the party and affiliated syndicates. The second consists of representatives elected directly by members of the party. These 20 elected members of the politburo then appoint six more members and, in addition, any member of the party who is a parliamentary deputy is automatically appointed a seat on the politburo (both of the latter being subject to an article in the party's bylaws stipulating that the number of appointed members be no more than one third the number of elected representatives).

Over the last several months, Hajj and Pakradouni stacked the deck in the congress by reducing the representation of the Metn district, where support for Gemayel is strongest, relative to other areas of the country. In addition, several vacant appointed positions were filled by opponents of Gemayel and other positions were eliminated, also to Gemayel's disadvantage.

As the date of the election approached, an atmosphere of threats and intimidation began to unfold. In mid-September, Lebanese security forces disrupted a memorial service in Ashrafiyah commemorating Gemayel's brother, the late President-elect Bashir Gemayel. An estimated 1,000 demonstrators chanting pro-Gemayel slogans marched to the church, the surrounding streets of which were cordoned off by security forces. After the service, violent scuffles quickly erupted and the police arrested four participants and briefly detained up to 36 others.

On September 19, Pakradouni revived accusations that Gemayel had embezzled millions of dollars from the purchase of Puma helicopters by the Defense Ministry during the late 1980s. He said that the parliamentary committee charged with investigating the matter had referred the case to Lebanese Prosecutor-General Adnan Addoum, a militant ally of the Syrian regime, and that the former president could be summoned for interrogation at any moment. This remark, widely interpreted as a veiled threat that Gemayel would be prosecuted if he continued opposing Pakradouni's ascension, invoked outrage among Gemayel's supporters. The following day, Addoum denied that the case had been referred to his office, but cautiously promised to "check" his records.

Not surprisingly, Pakradouni easily won the elections, receiving the votes of 74 out of the 90 members of the Phalange congress who showed up for the session (13 did not attend). Maurice Saba, a late entry into the race, won 15 votes and one member abstained.

After his election, Pakradouni declared, "We shall be the party of the president, the army and the judiciary" - the three governmental institutions most dominated by Damascus.8 In the days that followed, he made courtesy calls to most prominent allies of the Syrians.

Pakradouni's new loyalty to Damascus was also evident after Hezbollah launched a major mortar and rocket attack on Israeli positions in the disputed Shebaa Farms area on October 22. Although two members of parliament criticized the attack and several newspapers suggested that the timing was counter-productive, Pakradouni effusively praised the operation. Noting that Israel "viciously attacks the Palestinians every day and is still occupying Syrian lands," Pakradouni expressed his support for "the right of Hezbollah and the Islamic resistance to carry out operations" against Israeli forces.9

Pakradouni's victory has essentially sidelined the opposition wing of the party and eliminated any institutional channel for its political expression within the system. Sources close to Gemayel complain that they cannot form their own political party because the state will not grant it a license.

Whether Gemayel will gravitate to the nationalist opposition camp headed by Aoun or seek to accommodate himself to the regime remains to be seen. Gemayel's opposition to the Lebanese government and its Syrian sponsors has hardly been unequivocal. Even when he has been most critical of the regime, Gemayel has expressed a willingness to cooperate with President Lahoud. Indeed, he has met twice with Lahoud since his return to Lebanon last year and had been openly calling for a third appointment in recent months. He is fond of telling reporters that he is open to cooperation with the president, though "not at any price."

In a bid, perhaps, to persuade Gemayel to lower his price, Prosecutor-General Addoum suddenly announced on October 11 that he had located a missing file relating to the Puma helicopter scandal during Gemayel's presidency and sent it for further investigation to the ministry of justice.

Notes

1 See John P. Entelis, "Belief System and Ideology Formation in the Lebanese Kata'ib Party," International Journal of Middle East Studies (Vol. 4), April 1973, pp. 148-162.

2 For a detailed account of Khawand's abduction, see The Methodology of Enforced Disappearances in Lebanon, Human Rights Watch, 1997. For an overview of Syrian kidnappings in Lebanon, see Syria and the Politics of Arbitrary Detention in Lebanon, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, January 2001.

3 The Daily Star (Beirut), 28 September 2000.

4 Al-Diyar (Beirut), 22 July 2001.

5 Al-Sharq al-Awsat (London), 11 August 2001 and 25 August 2001.

6 The Daily Star (Beirut), 28 September 2000.

7 The Daily Star (Beirut), 28 August 2001.

8 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 5 October 2001.

9 The Daily Star (Beirut), 28 August 2001.