|

| Vol. 3 No. 7 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | July 2001 |

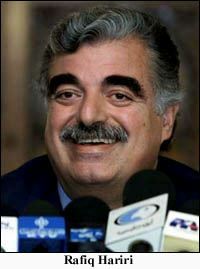

| | Dossier: Rafiq Hariri Prime Minister of Lebanon |

|

Most Lebanese feel a peculiar sense of pride toward Rafiq Hariri, though many will not readily admit it. In a country where political power has been thoroughly monopolized by outsiders, economic power commands a great deal of grudging respect and admiration. That Hariri is not a member of the traditional political elite and built his financial empire from scratch makes his ostentatious displays of wealth even more captivating.

However, the prime minister is also regarded by many as having sold the country to Syria and destroyed its economy during the course of his life-long drive to enter the ranks of Lebanon's political establishment.

Background

Rafiq Bahaa Edine Hariri was born in the Lebanese town of Sidon in 1944, the son of a Sunni Muslim farmer and greengrocer. Upon completing his secondary education in 1964, Hariri enrolled at the Beirut Arab University to study accounting. During this period, he was an active member of the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), a forerunner of George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and is said to have worked occasionally as a bouncer at its fundraising events.

|

As a result of his reputation for dependable work (he built the Taif Massara Hotel in only six months to host an Islamic Summit.), Hariri won the respect of the royal family and was granted Saudi citizenship in 1978. By the early 1980's, Hariri had become one of the 100 richest men in the world and his business empire expanded to include a network of banks in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, as well as companies in insurance, publishing, light industry, and other sectors.

Hariri poured a considerable amount of money into philanthropic projects in Lebanon, which was embroiled in war at the time. In 1979, he founded the Islamic Institute of Higher Education in his native town of Sidon. That same year, he established the Hariri Foundation for Culture and Higher Education, which has paid the tuition fees for thousands of Lebanese students at universities in Lebanon, Europe and the United States. In 1983, he built a hospital, a high school, a university, and a large sports center in Kfar Falous, Lebanon.

Hariri also contributed to early reconstruction efforts during lulls in the Lebanon war. Fleets of brightly-colored trucks and construction vehicles displaying the logo of Hariri's company, Oger Liban, were sent, free of charge, to clear rubble and repair roads in the capital during the early 1980's.

One day, Hariri drove up to the Lebanese presidential palace followed by a truck full of workers and building materials. "His workers emptied the truck and constructed, in one of the palace halls, a mock-up of a new downtown Beirut as Hariri perceived it," recalled former Lebanese Foreign Minister Elie A. Salem.1

However, Hariri is also said to have heavily financed opposing militias during the war, the very same militias that destroyed the central business district he dreamed of rebuilding. Critics such as former deputy Najah Wakim would later accuse him of helping to destroy downtown Beirut in order to rebuild it again and make billions of dollars in the process.

During the 1980's, Hariri acted as Saudi King Fahd's personal emissary to Lebanon, often heading Saudi mediation efforts. Most notably, he helped negotiate the participation of all warring sides in a National Dialogue Conference in Geneva in November 1983, as well as a second conference in Lausanne the next year. While ostensibly remaining the Saudi envoy to Lebanon, "Hariri, sensing where the power was, spent more time in Damascus than in Beirut."2 Realizing that the road to a political future in Lebanon ran squarely through Syria, Hariri worked feverishly to ingratiate himself to the Assad regime. His construction company built a new presidential palace in Damascus as a gift to the Syrian dictator (Assad apparently didn't care for the sprawling complex, which is now a glorified conference center).

Hariri often mediated between Damascus and various political figures in Lebanon during the last decade of the Lebanon war. In 1986, he brokered former Lebanese Forces (LF) commander Elie Hobeiqa's return to Lebanon and financed his establishment of a pro-Syrian Christian militia in Zahle. He was also a key player "mediating" between Lebanese President Amine Gemayel and the Syrians, who repeatedly torpedoed national reconciliation proposals that did not grant Damascus sweeping power over Lebanon. In the fall of 1985, Hariri sought unsuccessfully to gain Gemayel's acceptance of the so-called Tripartite agreement, which would have explicitly legalized Syria's military occupation of the country. Another round of mediation efforts in 1987 proved fruitless as well.

In August 1987, Hariri launched a bold initiative to break through the political impasse between the Syrians and Gemayel. According to Abdallah Bouhabib, then Lebanon's ambassador to Washington, Hariri offered Gemayel $30 million to resign the presidency six months before the end of his term, while offering the Syrians $500 million to permit the succession of Johnny Abdo, the head of Lebanese army intelligence, who would then appoint Hariri prime minister. Gemayel refused.3

In the fall of 1988, Syria and the Lebanese Forces militia brought about a political crisis by refusing to permit parliament members in areas under their control to convene and elect a new president. Fifteen minutes before the expiration of his term, Gemayel appointed a military caretaker government, headed by then-Army Commander Michel Aoun as interim prime minister, to run the country a new president could be elected. After Aoun's attempt to oust Syrian forces ground to a halt in the summer of 1989, Hariri helped organize a "national reconciliation" conference of Lebanese parliament members in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Hariri and his Saudi backers helped persuade (or, according to some sources, bribed) the delegates to formally accept Syrian control over the country.

After Syrian forces invaded east Beirut in October 1990 and swept away the last remnants of Lebanon's First Republic, Hariri returned to Lebanon and began negotiating reconstruction contracts with the Syrian-installed government. Hariri paved the way for his premiership by personally "donating" a lavish Beirut home to President Elias Hrawi and bribing various other political elites. In return for Hariri's pledge to guarantee Lebanese government loans, Hrawi appointed one of the construction magnate's trusted aides, Fadel Shallak, to lead the government's Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) and parliament passed a law granting CDR sweeping powers to dispossess landowners. By the summer of 1992, Hariri was at the helm of reconstruction planning in the capital, which many had already begun to dub "Haririgrad." Having purchased major shares in several radio and television stations, newspapers and magazines, Hariri was soon being hailed by the Lebanese media as an economic savior.

During the summer and fall of 1991, however, Damascus authorized an escalation of Hezbollah attacks against Israeli forces in south Lebanon, setting off a spiral of reprisals and counter-reprisals that dramatically undermined domestic and international confidence in the Lebanese economy. As a result, the value of the Lebanese currency plummeted and the inflow of capital into the country dried up. In early 1992, the Lebanese Central Bank spent one-third of its foreign exchange reserves in a futile attempt to support the currency, but the crisis continued to worsen. By May 1, the exchange rate had fallen to 2,000 Lebanese pounds to the dollar. General strikes quickly paralyzed the country, as offices and businesses owned by pro-Syrian political elites were ransacked by mobs of protestors.

Meanwhile, the ambitious billionaire began speaking publicly for the first time about his belief in the "shared destiny" of Lebanon and Syria in a clear bid to reassure Damascus that he would not contest its control over the country. Syria's reluctance to hand political power to this towering financial giant gradually diminished. After orchestrating the 1992 parliamentary elections to produce a compliant parliament, the Syrians handed the premiership to Hariri.

Hariri I (1992-1998)

Hariri's appointment was greeted with tremendous enthusiasm by most Lebanese. Within days, the value of the Lebanese currency soared by 15% as a mood of optimism swept the country. Hariri, who had close contacts in the United States, Europe, and the Arabian Gulf, also inspired greater confidence abroad. Most importantly, the new prime minister was granted considerable autonomy over economic (but not security) affairs by Syria, which continued its military occupation.

Hariri promptly declared that he would restore Lebanon's pre-war position as a regional business and finance hub. Lebanon, he said, would become the "Singapore of the Middle East." In an effort to attract foreign and expatriate capital, Hariri slashed income and corporate taxes to a flat 10% and borrowed billions of dollars to rebuild the economic infrastructure of the country. It soon became evident that Hariri's reconstruction plan, called Horizon 2000, would focus on rebuilding Beirut at the expense of the country as a whole, prioritize the financial sector over agriculture and industry, and emphasize the development of physical infrastructure rather than human capital. Proponents of this plan argued that a revitalized financial sector would become an engine driving economic growth for the entire country.

Hariri approached this daunting task in much the same manner as he conducted his private business affairs. Several key business associates of the prime minister were given high-ranking positions in the new government. Fouad Siniora, the chief financial officer for Hariri's business empire, was appointed finance minister. One of his company's lawyers, Bahij Tabbara, became justice minister. Riad Salameh, who had handled Hariri's account at Merrill Lynch, was appointed head of the Central Bank. The new governor of Mount Lebanon, Suhail Yamut, had previously been in charge of the prime minister's business interests in Brazil. Farid Makari, the vice president of Saudi Oger, later joined Hariri's cabinet as information minister.

The Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut's Central District (commonly known by its French acronym Solidère), in which Hariri is the primary shareholder, expropriated most property in the central business district of Beirut, compensating each owner with shares in the company (which, in some cases, were worth as little as 15% of the property's value). That Hariri and his business associates profited immensely from this project was an open secret.

|

Hariri and his protégés were not the only beneficiaries of this spending spree. In order to secure support from the motley strata of militia chieftains and pro-Syrian ideologues that Damascus had installed in the government, Hariri allowed kickbacks from public spending to enrich all major government figures. For example, a contract to build a section of the coastal motorway was awarded to the firm of Randa Berri, the wife of Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, at a price estimated to be at least $100 million in excess of construction costs. Contracts for the import of petroleum were awarded to the two sons of President Elias Hrawi.

Economic growth initially rebounded (reaching 8% in 1994), inflation fell from a previous high of 131% to 29%, and the Lebanese pound stabilized. However, the fruits of Lebanon's brief economic boom were restricted to the upper class and over a quarter of the population continued to live beneath the poverty line. Catering to the privileged class of commercial elites and pro-Syrian former warlords who exercised influence in Lebanon, the government slashed social expenditures and public sector wages, while opposing labor union demands for wage increases.

Increasingly, the government resorted to coercion in order to silence criticism of the growing inequity that resulted from Hariri's policies. The government banned public demonstrations in 1994 and relied upon the Army, which had now swelled to 45,000 men, to enforce the decree. In July 1995, a general strike which looked set to instigate a repeat of the 1992 disturbances was easily suppressed by the advance deployment of army units in the streets of the capital. When the unions called two general strikes in 1996, security forces again cracked down heavily.

In return for a relatively free hand in economic matters, Hariri cooperated with Syria's drive to consolidate its control over Lebanon. Under the guise of "regulating" the audiovisual media, the regime placed control of all major television and radio stations in the hands of pro-Syrian elites. Supporters of Aoun were perpetually harassed and detained, while the Lebanese Forces (LF) movement was banned and its leader, Samir Geagea, imprisoned.

Hariri further strengthened his support in Damascus by bribing leading Syrian officials and their families, particularly military and intelligence officers stationed in Lebanon. He has, for example, frequently paid college tuition fees for the children of prominent figures in the Assad regime (spawning jokes to effect that these "scholarships" exceeded the number of poor Lebanese sent to college by the Hariri Foundation) and provided Syrian officials with preferential business contracts in both Lebanon and Saudi Arabia.

The greatest gift that Hariri bestowed upon the Syrians came indirectly. Hariri is reported to have channeled an estimated 3.2 billion francs to the political campaigns of French President Jacques Chirac and his allies.4 To no one's surprise, Chirac reversed his predecessor's tough stance on the Syrian occupation of Lebanon (the previous government of French President François Mitterrand had gone so far as to push for UN Security Council Resolutions condemning Syria's October 1990 takeover of Beirut) and began a policy of appeasement far surpassing that of any other Western government.

By 1998, however, the Lebanese economy was on the verge of catastrophe and the Syrians began to see Hariri as a liability. As a result of Hariri's freewheeling public spending and rampant government corruption, Lebanon's national debt had soared from $2.5 billion to $18.3 billion, the largest per capita public debt of any emerging market (debt servicing accounted for 40% of the government budget). Economic growth slowed from 8% in 1994 to under 2% in 1998.

Ironically, Hariri's connection with long-standing figures in the Assad regime proved to be a double-edged sword. During the late 1990's, Bashar Assad, the son and heir apparent of ailing Syrian dictator Hafez Assad, began a concerted drive to consolidate his authority within the regime and weaken potential opposition to his succession. Many members of the regime's "old guard" had close ties to Hariri and had grown wealthy as a result of their association with the prime minister. Bashar, who had taken control over the "Lebanon file" as part of his political apprenticeship, decided to oust Hariri. Gen. Emile Lahoud was installed as president and a new prime minister, Selim al-Hoss, was brought in to "reform" the economy.

After Hariri's ouster, the new Hoss administration launched an "anti-corruption" campaign that targeted appointees and political allies of the former premier, while the state-run media relentlessly sought to discredit the billionaire. However, the Syrians ordered President Lahoud to abruptly halt the anti-corruption drive after it became clear that the investigations would risk exposing the illicit activities of Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, and other high-ranking Syrian figures. Lahoud, who depended on the anti-corruption campaign to bolster his public support, reportedly met with Bashar Assad and begged him to replace Kanaan with his brother-in-law, Maj. Gen. Assef Shawkat. Assad, however, was unwilling to risk such a shake-up.

Over the next two years, the initial wave of cautious public support for the Lahoud/Hoss administration dissipated as the country descended into economic recession. In the fall of 2000, the Syrians began rebuilding their bridges with Hariri in advance of the 2000 parliamentary elections. After the construction tycoon and his political allies triumphed at the polls, Hariri was again appointed prime minister.

Hariri II (2000-present)

Hariri's second tenure in office began, not surprisingly, with much less public fanfare than his first. The economic crisis that had hit Lebanon left little room for optimism and the prime minister had long ago shed his image as an economic miracle worker.

On the other hand, the depth of Lebanon's economic crisis has generated intense pressure on Hariri from the IMF and World Bank to undertake much-needed economic reforms and the prime minister has pledged to reduce the size of the government's bloated bureaucracy, privatize inefficient public sector industries, and cut government spending. There is also a strong consensus within the political establishment with regard to economic reforms (in principle, if not in practice).

Syria, of course, is the primary obstacle. Economic reforms threaten to undermine the networks of elite patronage employed by Damascus to maintain the loyalty of Lebanon's political establishment. More importantly, the resumption of Hezbollah's war against Israel last fall was a clear indication that the country's economic recovery would take a back seat to Syrian strategic interests. In order to ensure that Hariri does not interfere, security-related ministries in the new government were placed under the control of loyal Syrian allies, instructed to bypass the prime minister and report directly to President Lahoud.

|

Syrian officials immediately began working feverishly to control the damage. The prime minister was summoned by Syrian officials and ordered to remain silent on the issue in what one source called the "sharpest rebuke" Hariri had ever received from Damascus. Meanwhile, the National Broadcasting Network quoted "judicial sources" as saying that "nothing will stop Aoun from being prosecuted if he comes back to the country." Shortly thereafter, Lebanese Prosecutor-General Adnan Addoum, who has close links to Syrian intelligence, told the press that "Premier Hariri was talking politics. It's up to the judiciary to make the decision." Justice Minister Samir Jisr openly declared that Hariri "doesn't have the jurisdiction" to let Aoun return.

Tensions between Hariri and the Syrians have been most evident on the issue of Hezbollah's resumption of attacks against Israeli forces. On February 15, Hariri told a group of investors in Paris that there would be no more cross-border operations by Hezbollah. "We have a clear agreement with our Syrian brothers in this matter," he said, "There will be no provocations on our part."5 Once again, Hariri announced a major policy shift without consulting the Syrians. And, once again, he was sharply rebuked. The very next day, Damascus authorized a Hezbollah attack, the first in nearly two months, that killed an Israeli soldier.

After Hezbollah launched another deadly attack on April 14, Hariri's newspaper, Al-Mustaqbal, published a front-page editorial questioning whether Lebanon can "bear the consequences of such an operation and its political, economic and social impacts."6 Syrian President Bashar Assad went ballistic and angrily canceled a scheduled meeting with Hariri in Damascus. For the next month, Assad refused to receive him (some have suggested that Syria secretly approved the editorial in order to bolster American support for Hariri and that the entire dispute was "manufactured").

Hariri has also angered the Syrians by opening private channels of communication with American officials, bypassing his foreign minister and other pro-Syrian officials. During his recent visit to the United States, Hariri attempted to exclude the Lebanese ambassador in Washington, Farid Abboud, who has close ties to Lahoud, from his meetings with US officials. The Syrians intervened and sent word to Hariri that Abboud must be included in all discussions with the Americans.

In recent months there has been widespread speculation in the Lebanese media that Syria will soon replace Hariri. Syrian officials, who frequently discipline wayward political allies by courting their political opponents, have begun reconciling with Tripoli MP and former Prime Minister Omar Karami. Syrian relations with Karami were frayed during the 2000 parliamentary elections, when Damascus lent its support to a rival electoral list headed by Health Minister Suleiman Franjieh. After the elections, Karami began meeting with Maronite Christian Patriarch Boutros Nasrallah Sfeir and issued calls for a "national dialogue" to discuss the Syrian occupation of Lebanon.

Shortly after the cancellation of Hariri's visit to Damascus in April, however, Karami was invited to the Syrian capital to meet with Assad. In early June, Syrian Vice-president Abdul Halim Khaddam and Franjieh attended a ceremony marking the 14th anniversary of the assassination of Karami's brother, the late Prime Minister Rashid Karami. "With Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri not being a guaranteed ally for Syria, and after former Premier Selim al-Hoss joined the group calling for reconsidering bilateral relations with Syria, the Sunni situation in the country also seems to be at risk," wrote political analyst Nawwaf Kabbara shortly thereafter. "The Syrians seized the opportunity of the anniversary and made a big deal out of it, in their attempt to reconcile with Karami."7

Conclusion

Hariri, for better or for worse, can be counted on to single-mindedly advance his own political interests at the expense of all other considerations. In the past, this has led him to appease the Syrians and silence internal dissent. Today, however, his political future depends on his success in implementing economic reforms and obtaining loans and investment from the international community. While Syria can, in principle, terminate Hariri's tenure at will, Damascus is depending on a Lebanese economic recovery to breath life into its own moribund economy. In short, despite the serious obstacles that Hariri faces, the prime minister probably has more leverage over the Syrians than any previous leader in Lebanon's Second Republic.

Notes

1 Elie A. Salem, Violence and Diplomacy in Lebanon (London: IB Tauris, 1995), p. 103.

2 Ibid., pp. 179-180.

3 Abdallah Bouhabib, Al-Daw'i al-Asfar: Al-Siyassa al-Amrikiyyi Tijah Lubnan (1991), p. 176.

4 See Rene Naba, Rafic Hariri: un homme d'affaires premier ministre. (Paris: L'Harmattan, 1999).

5 Quoted in Nicholas Blanford, "Hizbullah Hoist by Its Own Petard," The Middle East, April 2001.

6 Al-Mustaqbal (Beirut), 15 April 2001.

7 The Daily Star (Beirut), 6 June 2001.