|

| Vol. 6 No. 1 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | Janury 2004 |

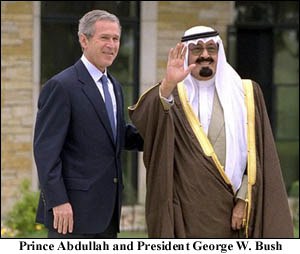

| | Dossier: Abdullah bin Abdel Aziz Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia |

Michael Gordon is a Middle East editor with the Economist Intelligence Unit and teaches courses on political Islam and the geopolitics of the Persian Gulf at New York University. He has also appeared on CNN and National Public Radio. The views expressed in this article are his own.

|

To some extent, this has happened. Far more in tune with public opinion than his predecessors, Abdullah asked the US military to find more welcoming arms in neighboring Qatar and distanced himself from the American invasion of Iraq. However, his efforts to shore up the royal family's battered reputation at home - both by adopting a more independent foreign policy and by introducing political and economic reforms - will ultimately help preserve the long-term viability of this relationship.

The Royal Maverick

Much of the venom directed at the House of Saud was born of decades of royal extravagance, and with respect to King Fahd, an unquestionable record of hedonism. These criticisms are especially poignant given that the House of Saud carefully built its legitimacy on its strong ties to the religious revivalist Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab (1703-1792) and his descendents. The support of the ulama (Islamic scholars) for the House of Saud since the founding of the kingdom in 1932 has been predicated on its adherence, at least superficially, to the world's most dogmatic interpretation of Islam.

However, while the population was forced to live by the repressive legalisms of religious law, the royal family, consisting of several thousand descendants of the kingdom's founder, Abdul Aziz bin Saud, lived extravagantly. Fahd had a history of alcohol abuse, in a country where the common citizen is lashed or arrested for possession, and frequently gambled in Europe, sometimes losing millions of dollars in a single night.[1] His sprawling estate on the southern coast of Spain and entourage of hundreds of servants were readily observable symbols of a lifestyle that clashed sharply with the piety the regime was supposed to represent.

Such profligacy wasn't a threat to stability so long as the standard of living remained high and the ultra-conservatives believed that the Islamic integrity of the kingdom was maintained, but the standard of living dropped precipitously after Fahd became king in 1982. After the 1991 Gulf War, when the stationing of US troops in the kingdom sparked a rise in Islamist dissent, the excesses of the royal family came under intense criticism.

Abdullah was cut from a different cloth. Born in 1924, he displayed a love of the desert and the Bedouin lifestyle from an early age. Eschewing "high politics," he spent his time immersed in the tribes, racing horses and patronizing their cultural activities. On the basis of his strong tribal ties, in 1962 Abdullah was appointed head of the National Guard, a direct descendant of the Ikhwan, the tribal army that served the kingdom's founder (and Abdullah's father) Abdel Aziz bin Saud in his early twentieth century conquest of the Arabian Peninsula. His modernization of the force, which now rivals the army in training and professionalism and constitutes the monarchy's first line of defense against domestic unrest, is quite an achievement in a country where princes are rarely known for hard work and dedication. The fact that Abdullah is hardly mentioned in radical Islamist tirades against royal corruption is a pretty strong indication that his reputation for integrity is well deserved.

Thus, Abdullah came along at the right time for the royal family (his ascension was based largely on seniority, but he could have been passed over), when it badly needed to project a more respectable face. Early on, Abdullah took steps to clean up the monarchy's image, such forcing princes to settle millions of dollars in unpaid phone bills. Much of this may have been window dressing, but the very fact that he so openly acknowledged that corruption was a problem was virtually unprecedented. His efforts to professionalize the bureaucracy were more far-reaching and endeared him to the educated classes. Fahd ingratiated himself to the technocrats by throwing money their way, but his "traditional" brother did it by actually modernizing and opening Saudi Arabia to the world. In July 2003, Saudi Arabia passed a comprehensive capital markets law that allows entry of more foreign banks and liberalizes the securities markets, two conditions necessary for membership in the World Trade Organization.

In response to a series of deadly terrorist bombings last year, evidently intended to destabilize the monarchy, Abdullah introduced a limited expansion of political and civil liberties. In October, Saudi Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal announced that elections for 14 municipal councils would be held within a year (though half of the seats will still be appointed). "We have reached the stage of development where the participation of the citizens of Saudi Arabia is a requirement," he added.[2] Although as yet there are no plans for elections to the Majlis al-Shoura (consultative council), a 120-member appointed body that advises the king, a June decree expanded its powers - it can now propose and debate (but not pass) legislation without getting prior approval from the palace. More recently, the crown prince allowed the council's deliberations to be televised for the first time.

In addition, the news media have been given considerably greater latitude. For example, liberal Saudis note that use of the term "Wahhabi" is no longer taboo. A number of legal reforms have also been introduced. A new criminal code forbids torture and criminal suspects are allowed access to lawyers.

For Abdullah and the leading princes who support his approach, developing greater political transparency is desirable primarily as a way to head off widespread discontent, not over lack of democracy per se. The move to liberalize is tactical - the population is granted representation (however limited) while the Islamists' already hazy message is further marginalized. Regardless of his intentions, a proposed loosening of the Al Saud's grip on power is a move that few would have expected from Abdullah given his "old-school" inclinations.

Abdullah's tribal background and reputation for piety have also enabled him to rein in the kingdom's religious zealots without fomenting open rebellion. Over 2,000 militant imams have been removed from the pulpit and hundreds jailed or sent for "reeducation." The religious police (mutawwas) have been curtailed - fewer are present in the streets and their treatment of citizens is less aggressive. Changes are gradually being introduced to an educational system geared toward Islamist indoctrination. It is doubtful that the monarchy could have presided over such changes without the austere Abdullah at the helm.

Abdullah on Foreign Policy

The most glaring policy difference between Fahd and Abdullah is the way in which they have approached foreign affairs. Throughout his tenure, Fahd wavered little in his US-centric approach. The strategic alliance was truly born in the late 1970s as instability in Iran made Saudi Arabia a key ally in the Gulf region. Both countries backed Iraq in its war with Iran (1980-1988) - the US with limited military hardware and Saudi Arabia with funding and moral support. Fahd's regime meshed well with that of the Reagan administration, which was resolute in countering Soviet influence in Iran and Afghanistan.

The strategic relationship blossomed in 1990 as both sides viewed the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait as a threat to regional security. Then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, along with General Norman Schwarzkopf, traveled to Saudi Arabia in August 1990 to meet with Fahd to propose a US-led coalition to face Iraq. Fahd gave his full support to the proposal, but Abdullah was initially opposed. He was unconvinced about the real threat Iraq posed to Saudi Arabia and concerned about the stationing of US troops in the kingdom without a sound exit strategy once the conflict was resolved. The difference of opinion between the king and crown prince with regard to the war demonstrated their fundamentally different views on US policy in the region.

What followed the Persian Gulf War in many ways did more to contribute to anti-Americanism in Saudi Arabia than the actual war itself. The continued presence of US troops on Saudi territory became a tangible reminder of the House of Saud's dependence on foreign powers for defense and legitimacy. Osama bin Laden's greatest early criticism of the US and the Saudi regime was based on this defense partnership. The stationing of a mass of non-Muslim and non-Arab personnel on Islam's holiest land is, according to the Islamists, heretical (Al-Qaeda's more recent tirades against Israel and its treatment of the Palestinians are afterthoughts designed to mobilize a larger contingency of followers).

Abdullah made no effort to sever this defense alliance, but to assuage the Islamists and the skeptical public (and in keeping with his own convictions), he refused in 2003 to allow the United States to wage war on Iraq from Saudi soil (keeping with the policy established during the Afghan conflict). By the end of the summer, the US had pulled out most of its military forces from Saudi Arabia. The lack of commitment to the war demonstrates a reaction to the political realities with which the Saudi regime now finds itself.

In an age of growing Arab resentment of the United States for its belligerency toward Saddam Hussein and unequivocal support for Israel, Abdullah has been careful not to appear to be kowtowing to US interests. To the chagrin of the United States, he allowed a charity run by his half-brother, Interior Minister Nayef, to compensate the families of Palestinian "martyrs." The plight of the Palestinians serves as a political tool - a way of deflecting criticism of the regime by allowing domestic Islamists and nationalists to vent their anger at Israel (and by default, the US).

Abdullah, like his predecessors, allowed this angst to grow, but as Israeli-Palestinian violence increased in 2001 and 2002, the Saudi regime was willing to dispense with this policy of benign neglect and forward a peace proposal. In February 2002, he casually proposed a resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which later became a full-blown peace plan as it gained momentum. In essence, Abdullah's plan provided for Israel's withdrawal to its borders prior to the 1967 war, giving up the West Bank and Gaza to the Palestinians. In return, the Arab states that have refused to recognize the existence of Israel since its inception in 1948 would establish normal diplomatic relations and trade relations with the Jewish state. King Fahd had proposed a similar plan in 1982, but did not lobby for it as forcefully. In the end, Abdullah's plan floundered, but it gave him a standing in the region that Fahd lacked.

Saudi Arabia under Abdullah has also warmed to the Iranian government of moderate President Muhammad Khatami. Since 1997, when Khatami was overwhelmingly elected on a reformist platform, several accords have been signed to improve cooperation on security and trade between the two countries. The improving relations of two of the Gulf's largest powers and traditional enemies should not be viewed as coming at the expense of US interests. Iran and Saudi Arabia share little in the way of common policy objectives and the enmity between the two countries will take years to dissolve. The reconciliation works to the advantage of the US, since the threat to Saudi Arabia by Iran is lessened with increased diplomatic activity.

Conclusions

Whatever their misgivings about Saudi foreign policy, officials in Washington recognize that Abdullah's efforts to modernize the kingdom, head off an Islamist takeover, and root out terrorism at home are less likely to succeed if he loses touch with the population. Radical Islamists can best hope to garner widespread public support for the violent overthrow of the monarchy by convincing the population that the royal family is relegating Saudi national interests behind those of the United States. His mildly critical view of US policy in the Gulf acts as a controlled pressure release, which diffuses tension in the kingdom rather than fuelling it, as a stronger pro-US stance would likely do. Despite the sound and the fury of recent bomb attacks throughout the kingdom, the presence of Crown Prince Abdullah at the helm will forestall any serious threats by the Islamists.

Loose comparisons can be made with the Islamist victory in Turkey in 2002. Although the religious-leaning party has its roots in the more conservative Islamic voting elements, its overwhelming victory is looked on with relief in the country since it represents a departure from the unstable and corrupted secular governments of recent years. An unbroken series of mistrusted governments with static policies would only engender more anxiety in the populace and lead to more social instability.

Notes

[1] For a more developed (and probably exaggerated) list of royal excesses, see Said Aburish, The Rise, Corruption and Coming Fall of the House of Saud (St Martin's Griffin, 1996).

[2] "Interview: Saudi Arabia says first elections reflect voters' desire for reform," Associated Press, 14 October 2003.

� 2004 Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. All rights reserved.