|

| Vol. 5 No. 10 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | October 2003 |

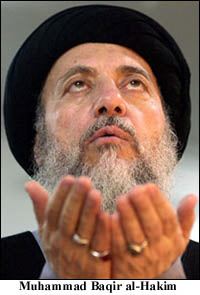

| | Dossier: The Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) |

Mahan Abedin is an analyst of Iranian politics, educated at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

|

On the surface, SCIRI has coped well since the assassination. Hakim's brother, Abdelaziz, quickly took over the reins and, rhetoric aside, appears intent on cooperating with the coalition authorities. But Abdelaziz's leadership is untested and he lacks the charisma of his slain brother. Although SCIRI has the resources to play a significant role in the evolution of the new Iraqi polity, balancing its relations with Iran and the United States in the volatile setting of postwar Iraq will remain a challenge.

Background

Baqir al-Hakim was central to the emergence of SCIRI. Hakim, born in Najaf in 1939, was a son of the late Grand Ayatollah Mohsen al-Hakim, an Iraqi cleric regarded as the leading marja' taqlid (source of emulation) in the Shiite world from 1955-1970. Like many young clerics of his day, Hakim joined the Daawa party after its establishment in the late 1950s. Though he officially disassociated himself from the party in 1960, he remained part of the broader current of Shiite political activism it inspired - leading to his arrest on three occasions in the 1970s.

Hakim was forced to flee Iraq in 1980 and eventually settled in Iran, where he helped organize former Daawa insiders and other Shiite activists under a succession of opposition fronts that later metamorphosed into SCIRI in November 1982. The price for his rebellion would be immediate and horrific - according to one report, the Iraqi regime killed 16 of his relatives in two days of murderous reprisal.[1] SCIRI set out to be an umbrella organization comprising several groups, including the Daawa party. However, the relations between the nucleus of SCIRI and Daawa became strained, largely because Daawa qualified its support for the Iranian revolution and viewed the rigid theocratic state that arose from it as unsuitable for Iraq. SCIRI officials claim that Daawa still remains part of its umbrella, but this is true only of one faction of the party.[2] By the mid-1980s, SCIRI was squarely centered around Hakim and other Najaf seminarians (and their lay proteges) who embraced Iran's Islamic Republic and its founding religious concept, velayat-e-faqih (guardianship of the jurisconsult).

SCIRI modeled itself as a conventional liberation organization, developing both political and military capabilities. Politically, it is governed by a General Assembly of 70-100 key personalities, including clerics belonging to Hakim's inner circle, military commanders of the Badr Corps (see below), and representatives of smaller Iraqi Shiite groups.[3] The General Assembly elects a 12-member Central Committee, SCIRI's highest decision-making body.

SCIRI was not a political success during the reign of Saddam Hussein. The Baathist regime's security apparatus was effective in containing its influence inside the country. Moreover, SCIRI's association with Iran damaged its credibility among non-Shiites in Iraq and undermined its legitimacy within the Shiite community. Charges that SCIRI is little more than an Iranian quisling are misleading, however - the Supreme Council and the Islamic Republic developed a strong relationship based on mutual influence. Many SCIRI leaders are of Iranian origin and some became so influential within the Islamic Republic that they assumed official positions in its government. Ayatollah Mahmoud Shahroudi, who briefly preceded Hakim as chairman of SCIRI , is now the head of Iran's judiciary.

Under the tutelage of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), SCIRI established a military wing in 1983, called the Badr Brigade. This force quickly grew into a full-fledged corps and joined regular IRGC forces on the front lines during the Iran-Iraq war. The relationship with the IRCG has persisted and deepened over the past two decades. The main Badr Corps training center, located just west of the Vahdati air force base in Dezful, and most of its other facilities in Western Iran and Tehran are IRGC property. The Badr Corps is believed to have between 10,000-15,000 fighters, though only around 3,000 are professionally trained (many of these being Iraqi army defectors and former POWs).

Like SCIRI's political wing, the Badr Corps never posed a serious threat to the former Iraqi regime. The main problem was that it strove to be a conventional military organization, equipped with heavy weaponry, rather than a guerilla force capable of easily infiltrating Iraq and operating clandestinely. While its conventional forces looked impressive on parade, their ineffectiveness was highlighted during the 1991 Shiite uprising in Iraq - Badr forces managed to cross the border, but were easily crushed by the Iraqi army. The military failure of SCIRI contrasted sharply with the accomplishments of the Daawa party, which developed a secretive, cell-based network of bombers and assassins that earned a reputation as Saddam Hussein's most fearsome enemy.

Prior to the fall of Saddam's regime, SCIRI operated out of a large headquarters in the Manoochehri district of Tehran and concentrated most of its resources in Iran. It also opened embassy-like offices in three Arab states neighboring Iraq - Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Syria, as well as in London, Paris, Vienna and Geneva.[4] The Damascus office, headed by SCIRI's foreign and Arab affairs chief Bayan Jabr, coordinated relations with other Iraqi opposition groups, while the London office, run by Hamid al-Bayati, served as a liaison with Western governments and media.

Relations with Washington

It was Hakim's political pragmatism and the influence of the Supreme Council's progressive and technocratic cadres that prompted SCIRI to establish and maintain ties with the United States. Formal links were forged in 1992, but informal contact started as early as 1989 when the strategic and global threat of the Saddam Hussein regime first began to be appreciated in Washington. Tentative contacts were made with the embryonic SCIRI office in Damascus, headed by Bayan Jabr.

Although SCIRI objected, for obvious reasons, to the Clinton administration's "dual containment" policy aimed at isolating Iran and Iraq simultaneously, it maintained surreptitious contact with Washington throughout the 1990s. American officials were keen on maintaining contact with SCIRI as well, largely due to the influence of Iraqi National Congress leader Ahmed Chalabi, who convinced them of SCIRI's pragmatism and broad popular support within the Iraqi Shiite community. In 1998, SCIRI was authorized to receive American funding through the Iraq Liberation Act-an offer it declined.

Chalabi was also said to have been instrumental in convincing SCIRI leaders that incoming US President George W. Bush was committed to overthrowing Iraq's Baathist regime - in contrast to the "silver bullet" strategy (getting rid of Saddam while leaving the regime intact) previously favored by many in Washington. In early 2001, Muhammad Hadi, a senior SCIRI leader in Iran, said that the group would welcome US efforts to oust Saddam Hussein.[5] Although SCIRI officials began expressing opposition to an American war in Iraq after Bush included Iran in his January 2002 "Axis of Evil" speech, privately they wanted to participate in planning for a post-Saddam Iraq.

As the prospect of a US-led invasion of Iraq became a near-inevitability in the summer of 2002, SCIRI resumed official contacts with the United States. In August 2002, a SCIRI delegation headed by Abdelaziz al-Hakim, Ibrahim Hamoudi (a senior political advisor) and Bayati visited Washington, along with representatives of five other opposition groups, and held marathon meetings with State Department and Pentagon officials to discuss the overthrow of Saddam. SCIRI also played a key role in the December 2002 London conference of Iraqi opposition groups and was awarded 15 of the 65 seats on the provisional governing council formed at that meeting.

In the months prior to the war, however, relations between the United States and SCIRI cooled - particularly after the Bush administration made it known in January that it would administer Iraq directly for some time after Saddam's overthrow, rather than handing power to a provisional Iraqi government. Hakim accused the United States of planning a colonial occupation and reportedly threatened that Badr forces would attack American troops if they outstayed their welcome.[6] In mid-February, a detachment of 1,000-1,500 Badr fighters crossed the border into northern Iraq and set up a base near Darbandikhan, an area under the control of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). About a week before the war, this force staged a provocative military parade, prompting American officials to warn that any armed Badr fighters encountered by coalition forces would be considered enemy combatants.

SCIRI in Postwar Iraq

SCIRI heeded Washington's warning not to interfere in Operation Iraqi Freedom. After the collapse of the Baath regime on April 9, however, large numbers of Badr fighters crossed from Iran into the province of Diyala. For reasons that still remain unclear, US forces desisted from entering this region for nearly 3 weeks, allowing Badr fighters to take control of several strategic towns, including Khanegheyn, Mandali, Moghdadiyeh, Shahraban and Khalis. Baqubah, the capital of Diyala province, was the scene of intense clashes for nearly two weeks between Badr forces and a collection of pro-regime elements, including Baath Party loyalists, local tribesmen loyal to Saddam and the Mojahedin-e-Khalq. Although American officials worried aloud about IRGC personnel crossing into Iraq with Badr forces, there was little evidence of this.

In late April, a force of 3,000 US marines arrived in Baqubah and set upon dismantling the Badr presence, reportedly seizing significant amounts of arms and killing a Badr fighter in a skirmish on the town's outskirts. Nevertheless, SCIRI remains strong in Diyala as is evidenced by the de facto political control it exercises over the towns of Shahraban and Khalis.

Another site of early attempts by SCIRI to flex its muscles was the town of Kut, where a senior SCIRI leader, Sayyid Abbas Fadhil, declared himself mayor. Abdelaziz al-Hakim returned from Iran on April 16 and was welcomed by Fadhil and a crowd of 20,000 cheering residents. Although Fadhil was later forced to back down, Kut remains a solidly pro-SCIRI town.

In the south of the country, SCIRI opened a large office complex in British-occupied Basra (the group's historically good relations with the United Kingdom may have facilitated this) and used it to extend its political influence in nearby town and villages. The extent of SCIRI's influence in the sacred Shiite towns of Najaf and Karbala is difficult to assess, but judging from the large crowds that turned out for Hakim's funeral, it is significant.

Upon his return to Iraq in May, Hakim told a large gathering in Najaf: "let them leave Iraq to its own people . . . the Iraqis are capable of providing security and protecting Iraq."[7] He later softened this demand, calling for the United States to hand control of the country over to the United Nations. "If the goal was to free Iraq-not exploit it afterwards-why not let the UN handle it as it has been in Bosnia and elsewhere," he said in early July.[8]

However, even as Hakim was condemning the American presence, his subordinates were busy negotiating with the coalition authorities to secure a role for SCIRI in shaping the postwar political order. A major issue of dispute was the American demand that the Badr Corps be disarmed. Weeks of furious exchanges between coalition representatives and SCIRI leaders over this demand, which Abdelaziz al-Hakim called "hostile" and "unjust,"[9] appeared for a time to preclude further cooperation. However, pragmatism prevailed and SCIRI began disarming.

This process did not go smoothly. In early June, coalition forces arrested around 20 Badr fighters who were, according to an American military spokesman, involved in "planning, supporting, financing and executing at least one RPG [rocket propelled grenade] attack on US forces and are suspected in several others," but they were apparently released.[10] Coalition forces have raided SCIRI facilities in search of weapons and incriminating documents. The pattern of SCIRI infractions does not appear to indicate planning for hostilities against coalition forces, but for adapting to the deterioration in security conditions that led to Hakim's assassination in August.

After Hakim's assassination, the Badr Corps established a heavy security presence in Najaf. Although the militia later reduced its presence on the streets, it still operates in the city. In mid-September, for example, armed Badr fighters stormed the residence of a former Baath party official in Najaf and took him away for questioning. A number of subsequent security breaches (most recently a mortar attack on the group's office in Kirkuk in early October that killed a SCIRI official) have led to calls for an even broader resurgence of the militia.

Officially, though, the Badr Corps is now the "Badr Organization for Development and Reconstruction" and its cadres have been put to work rebuilding infrastructure and other humanitarian projects. SCIRI hopes that its fighters will eventually be absorbed into military and police units under the control of the Governing Council, but has complained that candidates from the Badr Corps are being rejected unfairly.[11]For nearly three months after the fall of Baghdad, SCIRI leaders adamantly refused to join any provisional Iraqi authority appointed by the coalition. However, the group abruptly dropped its objections on July 7, reportedly as a result of "vigorous" mediation by the UN special representative in Iraq, Sergio Vieira de Mello, and a change in the body's name from "Political Council" to "Governing Council."[12] Later that month, Abdelaziz al-Hakim took his seat on the council. In early September, Jabr left Syria for Baghdad to assume the post of Reconstruction and Housing Minister in the newly unveiled Iraqi cabinet (SCIRI also assumed control of the Ministry of Sports and Youth).

However, there are still major political disputes between SCIRI and the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) - most notably the group's demand that Iraq's permanent constitution be drafted by "a panel elected by the Iraqi people," rather than a committee appointed by the Governing Council - the method favored by the coalition authorities.[13]

Relations with other Iraqi groups

SCIRI has enjoyed good relations with both main Iraqi Kurdish factions - the PUK and the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), especially the former, as PUK leader Jalal Talebani has been a key ally of the Islamic Republic for more than 2 decades. SCIRI's relationship with the INC has also been relatively free of tensions for the past decade, but the overtly secular orientation of the INC and its close relationship with the US is likely to make future cooperation more problematic.

SCIRI relations with Sunni (or predominantly Sunni) factions have ranged from cool to hostile. SCIRI is anathema to secular Arab nationalists who fear Iranian domination, while some Sunni Islamists see the resurgence of Shiite religious freedom as a threat. In early September, the Council of Ulema, a grouping of Sunni clerics established five days after the fall of Saddam's regime, accused Shiite clerics of seizing control over 18 Sunni mosques around the country, calling it "a grave phenomenon akin to ethnic cleansing and the Balkanization of Iraq."[14] Nevertheless, it must be borne in mind that Sunni Islamists also suffered immensely under Saddam and many developed ties with SCIRI while in exile. Serious conflict between Shiite and Sunni Islamists in Iraq is unlikely to materialize in the near future.

Ultimately, SCIRI's long-term political future will be determined mostly by its appeal within the Shiite community. Broadly speaking, it must contend with three alternate poles of Shiite loyalty.

The first is the Hawza al-Ilmiya, a network of seminaries in the holy city of Najaf run by the highest-ranking clerics (marjaiyya) in Iraq, of whom Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani is acknowledged to be supreme religious authority by Iraqi Shiites.[15] The marjaiyya tend to embrace traditional Shiite political quietism and have tacitly supported the American occupation. Although widely revered, Sistani's ability to mobilize Iraqi Shiites politically remains untested.

The second pole is the Sadrists (sadriyyun), or followers of Muqtada al-Sadr, a young fire-brand cleric who draws his support mainly from the two million desperately poor Shiites living in an eastern suburb of Baghdad now known as Sadr City. Although lacking substantial religious credentials, he is the son of the late Ayatollah Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr, an esteemed cleric killed by the Iraqi regime in 1999. Sadr has repeatedly called for American forces to leave Iraq (while carefully avoiding direct incitement of violence) and recently set up his own "government" as a rival to the Governing Council. He has publicly attacked both Sistani and Hakim for collaborating with coalition forces. The marjaiyya view him with extreme distaste.

The third pole is the Daawa party. Daawa's spiritual leadership is composed of a multiplicity of personalities with different views and allegiances, but its cohesive activist network is led by the formerly London- based Ibrahim Jaafari, who was given a seat on the Iraqi Governing Council and served as its first president. Daawa is still too fractured and secretive to play a decisive role in Iraqi politics. In any event, it has observed an unwritten rule of avoiding open disputes with SCIRI for many years.

Despite the challenges to its centrality the upshot is that amongst the former Iraqi opposition forces SCIRI is by far the best organized and capable. It is also more popular than its detractors would admit. The control it exercises in several important Iraqi towns and the collective outpouring of grief following Hakim's assassination is testament to this.

SCIRI has sought to coax the quietist marjaiyya of Najaf out of their political apathy - not by questioning their authority (as the Sadrists have done) but through its leverage in the Hawza. It has had some modest successes, as Ayatollah Sistani has been making increasingly political statements recently. For example, Sistani has come out in support of SCIRI's call for an elected panel to draft Iraq's constitution.

Although SCIRI's relations with the Daawa party and the marjaiyya remain good, its relationship with the Sadrists has been marked by tensions. Nevertheless, this rivalry is not yet as explosive as some have suggested. Asked if a rival Shiite faction may have been responsible for the killing of Hakim, Jabr replied, "I totally rule this out . . . Throughout hundreds of years, the holy city of Najaf has witnessed only conflicts of ideas and dialogue of thoughts. Such acts are alien to the city of Najaf and to Shiite religious action."[16] In fact since Hakim's assassination SCIRI's relations with the Sadrists have improved.

Conclusion

SCIRI is not just sponsored by Iran - its leaders are ideological compatriots of the Iranian clerical establishment and many of them are of Iranian descent, while its military commanders have worked closely with the IRGC for twenty years. However, fears that this relationship will eventually put SCIRI on a collision course with the United States are exaggerated. Notwithstanding the call for "Islamic Revolution" emblazoned in its name, SCIRI is officially committed to democracy and pluralism in Iraq. "You can't have a government based on a religious Shiite principle when you have other ethnic and religious groups," said Bayati in a May 2003 interview with Middle East Intelligence Bulletin.

While the dynamics of operating within Iraq's emerging democratic polity are unlikely to seriously weaken SCIRI's relations with Iran, its leaders believe that the movement's future now depends in the short term on cooperation with the United States and in the long-term on mobilizing support among Iraqi Shiites and maintaing good relations with Sunni and Kurdish groups. SCIRI will continue to make defiant statements and bemoan the occupation, but on the ground it is preparing for post-occupation Iraq and intent on avoiding confrontation with the United States. As long as SCIRI remains confident that American forces will leave Iraq on terms broadly suitable to the pursuit of its long-term interests, a confrontation is unlikely.

Notes

[1] Valentinas Mite, SCIRI Head Killed in al-Najaf, RFE/RL, 29 August 2003.

[2] The leading personalities of Daawa's pro-SCIRI faction include Mohammad Mehdi Asefi, Mohammad Ali Taskhiri, and Kazem Haeri (who is also close to Muqtada al-Sadr). Daawa is no longer represented on SCIRI's central committee.

[3] These include Al-Jund al-Iman, led by Sayyid Sami al-Badri; Monazemat al-Amal, led by Sheikh Mohsen al-Hosseini until his death in August; and al-Daawa al-Islamiyah (a splinter group from the main al-Daawa party), led by Izeddin Salim.

[4] SCIRI also has accredited representatives in Canada, Holland, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Australia.

[5] The Associated Press, 7 April 2001.

[6] Juan Cole, Shiite Religious Parties Fill Vacuum in Southern Iraq, Middle East Report, May 2003.

[7] Al-Ahram Weekly, 15-21 May 2003 (Issue No. 638).

[8] The Associated Press, 7 July 2003.

[9] Pravda, 27 May 2003.

[10] "US soldiers raid Baghdad office of Shiite party amid heightened tensions," Financial Times, 9 June 2003.

[11] Author's interview with Hamid Bayati, 13 October 2003.

[12] "The classic dilemma of collaboration: Iraqi leaders have to weigh up the risks of working with the occupiers," The Guardian (London), 16 July 2003.

[13] "Iraqi Shiite leader demands election of constitution drafters," Agence France Presse, 3 October 2003.

[14] "Iraq's Sunni Muslims accuse Shiite majority of "ethnic cleansing," Agence France Presse, 2 September 2003.

[15] The Afghan Shiite community looks to Ayatollah Muhammad Ishaq Fayyad, while South Asian Shiites see Ayatollah Bashir Najafi (who is of Pakistani origin) as their most supreme religious authority.

[16] Arab Republic of Egypt Radio (Cairo), 29 August 2003. Translation by BBC Monitoring.

� 2003 Middle East Intelligence Bulletin. All rights reserved.