|

| Vol. 4 No. 1 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | January 2002 |

|

While Lebanese and Syrian officials insist that Israel carried out the killing, a number of individuals, political groups and governments had more compelling and immediate motives to eliminate Hobeika. Moreover, the timing and location of the assassination are strong indications of Syrian involvement.

The Rise of a Lebanese Warlord

Hobeika was born in 1956 in the Lebanese village of Qleiaat. In his early teens, Hobeika joined the Christian nationalist Phalange (Kata'ib) party, which staunchly opposed the autonomy of Palestinian guerrillas in Lebanon and began to arm itself in the early 1970s. After the outbreak of war in Lebanon between Christian militias and a coalition of Palestinian and leftist groups in 1975, Hobeika distinguished himself as a ruthless warrior, earning the nickname "HK," after the Heckler and Koch sub-machinegun he carried. He steadily rose through the ranks of the Phalange, which had defeated rival Christian militias by July 1980 and incorporated them into the Lebanese Forces (LF). In 1978, Hobeika became head of the LF's security agency (jihaz al-amin). In the years that followed, he developed close ties with both the Israeli military and the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

At the time of Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Hobeika was the principal military liaison to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). When Israeli forces took over west Beirut, Hobeika was eager to settle old scores with the Palestinian refugees living there, particularly after the assassination of the LF's commander, President-elect Bashir Gemayel, which was at first erroneously blamed the Palestinians. In September, Hobeika ordered LF militiamen into the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps on the outskirts of the city, which had recently been evacuated by the PLO. Over the next three days, LF forces killed over 800 residents of the camp.

Israel's Kahan commission conducted an extensive inquiry into the massacre which revealed Hobeika's central role. An Israeli officer who overheard internal LF radio communications during the massacre later testified before the commission that a militia officer who had rounded up dozens of women and children called Hobeika to ask what he should do with them. "This is the last time you're going to ask me a question like that," said Hobeika, who is believed to have watched the massacre from the rooftop of a building near the Kuwaiti embassy in west Beirut, "you know exactly what to do." The commission's report added that this exchange was followed by sounds of "raucous laughter."

The commission's conclusion that then-defense minister Ariel Sharon bore indirect responsibility for the massacre was based in part on the notoriety of Hobeika and the militia forces under his command. "Everyone who had anything to do with events in Lebanon should have felt apprehension about a massacre in the camps if armed Phalangist forces were to be moved into them without the IDF (Israeli Defense Forces) exercising concrete and effective supervision and scrutiny."

Hobeika was involved in a second massacre in March 1985 that would later come back to haunt him. The American CIA reportedly paid Hobeika (through Lebanese army intelligence officers) to assassinate Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah, the spiritual leader of the militant Shi'ite group Hezbollah, considered by US officials to have taken part in planning the October 1983 bombing of the US marine barracks in Beirut which killed 241 servicemen. However, the assassination attempt that Hobeika carried out was not the surgical operation that his benefactors had hoped for - the car bombing near Fadlallah's residence killed dozens of bystanders but left the intended target unscathed. The massacre led the CIA to terminate its relationship with Hobeika and gave Hezbollah a lasting grudge against him.

That same month, Hobeika joined Samir Geagea and Karim Pakradouni in revolting against LF commander Fouad Abu Nader, who had begun to follow the lead of his uncle, President Amine Gemayel, in reconciling with Damascus. After Geagea stepped down from the joint leadership of the LF a few months later, Hobeika advanced to the top of the militia's political hierarchy. Hobeika, who was until then a staunch opponent of Syrian intervention in Lebanon, abruptly realigned himself in hopes of reaching an agreement with Syrian-backed militias and assuming the presidency in a Syrian-dominated post-war republic. In September 1985, he traveled to Damascus. The leader of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) militia, Walid Jumblatt, reportedly asked Syrian Vice-President Abdul Halim Khaddam why he was negotiating with "this murderer," to which Khaddam replied, "Who in Lebanon is not a murderer?"1

In December, Hobeika and Pakradouni joined Jumblatt and Amal leader Nabih Berri in Damascus to sign the Tripartite Accord, an agreement between the country's three top militias that would have legalized the Syrian presence in Lebanon. After details of the accord were published in the Lebanese press, however, Christian opposition to the agreement grew rapidly. In January 1986, rebellious LF forces led by Geagea, with help from Amine Gemayel's partisans, seized control of east Beirut and Hobeika fled to France.

Although he was discredited within his own Christian community, Hobeika was encouraged by Khaddam and Lebanese financier (and future prime minister) Rafiq Hariri to return to the country and establish his own militia in Syrian-occupied areas. For the next five years, Hobeika served his new patrons and awaited the day that his support for Damascus would be rewarded.

|

After Syria invaded east Beirut and ousted Michel Aoun in October 1990, completing its conquest of Lebanon, Hobeika was twice "elected" to parliament and occupied several important cabinet positions. Hobeika's post-war political career is a good illustration of why most Lebanese feel such intense skepticism toward their government. After having contributed so substantially to the creation of hundreds of thousands of internal refugees and handicapped persons injured during the war - two of the most pressing social problems in postwar Lebanon - Hobeika was appointed minister of the displaced (October 1991) and minister of social affairs and the disabled (November 1992). In May 1995 he was appointed minister of electricity and water resources, a post he held for over three years.

However, unlike other Syrian-backed militia warlords that occupied positions of influence in postwar Lebanon, such as Jumblatt and Berri, Hobeika's sordid wartime past proved to be an insurmountable obstacle to his political ambitions. Unlike Jumblatt (and, to a lesser extent, Berri), Hobeika's political alignment during the latter half of the war was completely at odds with the consensus prevailing within his own sectarian community. Moreover, whereas Jumblatt strictly refused to contemplate the assassination of political rivals and Berri did so only sparingly, Hobeika ordered hits on other politicians with reckless abandon. Not surprisingly, he continued to be distrusted even by other pro-Syrian politicians.

Moreover, his role in the Sabra and Shatila massacre made him taboo in respectable circles. When the editors of Time magazine were hosted at a state dinner in Lebanon, Hobeika was seated at a table without journalists. Over the years, he tried to exonerate himself by giving a range of completely different accounts regarding the massacre. On some occasions he claimed that he was in Sweden at the time of the massacre, at others he said he was in Beirut, but busy investigating the murder of Gemayel. Last year, he acknowledged that he was involved in the massacre during an interview with the BBC, but said he was merely "carrying out orders." These inconsistencies have had the effect of confirming, rather than questioning, his presumed guilt in the eyes of the public.

Hobeika's Fall from Grace in Syrian-Occupied Lebanon

In 1999, Hobeika's former bodyguard, Robert Maroun Hatem (alias Cobra), published an exposé accusing his former boss of masterminding numerous assassinations, assassination attempts, kidnappings and other wartime atrocities. Although the book, entitled From Israel to Damascus, was banned in Lebanon, it was widely read on the Internet and caused an enormous public uproar.2

The most damaging allegations made by Hatem in the book and in subsequent press interviews (most of which were later confirmed by former LF security chief Asaad Shaftari) linked Hobeika to the following: the 1978 assassination of Zghorta MP Tony Franjieh (in conjunction with Geagea), the assassinations of several rival figures in the LF, the execution of four Iranian diplomats abducted by the LF in 1982, the kidnapping of businessmen Roger Tamraz and Charles Chalouhi, a 1984 attempt to assassinate then-Education Minister Selim al-Hoss, and a 1985 attempt to assassinate MP Mustafa Saad.

Unfortunately for Hobeika, Selim al-Hoss happened to be prime minister at the time the book was published. Not surprisingly, Hoss opened an investigation into the 1984 assassination attempt, which killed his driver and a number of innocent bystanders. Another victim who remained influential in Lebanese politics, Mustafa Saad, demanded an inquiry into the 1985 attempt on his life, which killed his daughter Natasha and left him severely handicapped.

Although Syria ensured that the investigation into the Hoss assassination attempt was dropped and that no investigations were launched into the other killings, the controversy was the beginning of the end of Hobeika's political career in Lebanon.

Prior to the August 2000 elections, Hezbollah officials objected when Damascus included Hobeika on the "Consensus and Renewal" list, a pro-Syrian electoral coalition running against allies of Druze leader Walid Jumblatt in the Baabda-Aley district, arguing that the former militia chieftain had the blood of thousands of Muslims on his hands. Although a compromise was reached to leave a slot on the list blank so that Hobeika's supporters could write in his name, Hobeika suffered a humiliating defeat in the elections.

Syria's refusal to secure Hobeika's inclusion in the electoral list reflected an important power shift in Damascus that took place as Bashar Assad assumed control of the regime from his father prior to the latter's death in June 2000. Hobeika's two principle allies in the regime - Vice-president Khaddam and former Army Chief-of-Staff Hikmat Shihabi were sidelined by Bashar, who came to regard Hobeika and several other Lebanese allies of the "Old Guard" as a liability.

Hobeika understood well the most important ramification of losing political influence - he was dispensable and no longer enjoyed top rank backing from Damascus. Without this, his enemies might be tempted to publicly expose details of his wartime atrocities and post-war illicit business dealings, or worse - take his life. Increasingly isolated, Hobeika maintained a low profile, working out of a nondescript office building in east Beirut where, according to one visitor, every window blind was closed.

Hobeika's fortunes plummeted further in June 2000, when Palestinian survivors of Sabra and Shatila filed charges against Ariel Sharon for his role in the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Belgium, under an unusual 1993 law that allows the prosecution of foreign officials for human right violations. That same month, the BBC aired a documentary of the massacre, entitled The Accused. Although the lawsuit did not mention Hobeika's role and the documentary was focused mainly against Israel , they led to vibrant public discussion of an issue that Hobeika would have preferred to leave buried.

Renewed public discussion of his role in the massacre coincided with his final attempt to regain political influence in Lebanon. Lebanese and Syrian intelligence officials had been meeting with former LF leaders who were willing to form a legalized LF political party to back Lebanese President Emile Lahoud. Press reports indicated that the Syrians had not yet decided whether the party would be headed by Hobeika or Fouad Malek, a former LF chief of staff.

In July, Hobeika set out to redeem his reputation by calling a press conference and declaring himself innocent of any involvement in the Sabra and Shatila massacres and in possession of "evidence of what actually happened . . . which will throw a completely new light on the Kahan commission report." Shortly thereafter he announced that he was willing to formally testify in Belgium once the court proceedings were underway.

Hobeika never publicly revealed what he intended to say in court. However, in a conversation last year with Fergal Keane, the director of the above-mentioned documentary, he offered an entirely new claim - that Israel had shipped in members of the South Lebanon Army (SLA) to commit the massacres. Since the fact that the militiamen were members of the Lebanese Forces has never been disputed (the contentious issue has always been who ordered the massacre) Keane did not take this claim seriously.3 Hobeika also claimed in recent months that former US envoy to Lebanon Morris Draper, who was in the country at the time to secure the election of Amine Gemayel as president, would vouch for him. While this would not have been a credible alibi in legal terms (Hobeika is alleged in the Kahan commission report to have given the orders by phone and it is doubtful that Draper was with him around the clock prior to and during the three day massacre), it certainly would have been good publicity.

Hobeika probably understood that mainstream intellectuals even in the Arab world would not believe his claims. But had he not attended at all, his role in the massacre would almost certainly have been brought up. With the proceedings guaranteed to be front page news in the Arab world, he would have been branded a war criminal in the court of public opinion. Moreover, it was extremely unlikely that witnesses would have been called to directly contradict his testimony - the court is clearly intent on focusing international attention on Israel and, in any case, no high-ranking Israeli or LF officials have agreed to testify.

Nevertheless, Hobeika's hopes for a political resurrection were dashed. In late November, Lebanese press reports indicated that the senior leadership positions in the new LF party had been decided, with Malek as president. Hobeika was infuriated by this snub.

|

In the aftermath of September 11, Hobeika attempted to win American support by contacting the CIA to offer his help in locating and capturing Imad Mughniyah, the former head of special overseas operations for Hezbollah who is listed on the Bush administration's most wanted terrorist list. Hobeika had collaborated with CIA operatives in Lebanon in the early 1980s and attended a training course at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia in 1982. His services would have been a valuable asset in the hunt for Mughniyah. Hobeika owned one of the largest private security firms in Lebanon (in effect, a small militia made up of bodyguards with legally-registered weaponry and skilled intelligence operatives) that has a presence in the largely Shi'ite southern suburbs of Beirut - the most likely location of Mughniyah.

It appears that the Syrians, who maintain close ties with Mughniyah, discovered Hobeika's attempts to contact the CIA. In early January, Lebanese Prosecutor-General Adnan Addoum opened an investigation into corruption at the Ministry of Electricity and Water Resources. There have been reports that two of Hobeika's associates when he was in charge at the ministry, Fadi Saroufim and Rudy Baroudi, would be called in for questioning. The practice of opening and closing judicial files has been an important method used by the Syrians, who engineered Addoum's appointment, to reward or punish Lebanese politicians.

During the last month of his life, Hobeika was extremely distraught due to the steadily escalating measures taken against him by the Syrian-backed regime in Beirut and became wildly paranoid. During the funeral of a close ally and confidante, former MP Jean Ghanem, who died on January 14 from injuries sustained in a car crash in Hazmieh, Hobeika told several people that the latter's death was not accidental.4

Prior to his death, Hobeika was considering leaving Lebanon. Earlier this month, according to an informed Lebanese source, one of the bodyguards who died in the January 24 attack (Mitri Ajram) told a friend in France that things were not going well for Hobeika and that he might take refuge in another country. Indeed, Hobeika had prepared for this contingency - his brother, Charles, recently emigrated to Canada and reportedly brought with him a large portion of Hobeika's fortune. In addition, two of his key aides left Lebanon last year to set up overseas businesses - Joseph al-Asmar in Tanzania and Fadi Saroufim in Kuwait.

The Assassination

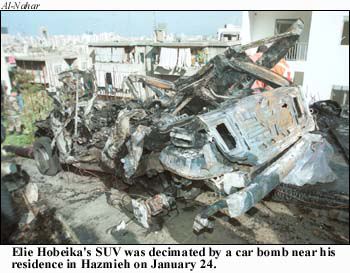

At 9:30 AM on January 24, Hobeika and three bodyguards left his apartment on Kamel Asaad street in suburban Hazmieh southeast of the capital en route to his office in Sin al-Fil. Shortly after their departure, the blue Range Rover they were driving slowed down to pass by a Mercedes parked on the side of a narrow road. At that instant, an estimated 22 pounds of TNT in the Mercedes suddenly detonated (apparently by remote control). The explosion reportedly catapulted the former warlord's charred remains over sixty meters from the wrecked SUV, killed a bystander and injured six others. The blast blackened neighboring apartment buildings, destroyed dozens of cars parked nearby, and even shattered glass windows up to one kilometer away from the scene.

Hours after the assassination, Lebanese Interior Minister Elias Murr held a press conference and announced that the authorities had "confirmation that Israel and its agents were behind this terrorist act." President Lahoud and Prime Minister Hariri also insisted that Israel was involved. Since categorical statements alleging Israeli involvement are generally made by Lebanese and Syrian officials whenever there are manifestations of anti-Syrian dissent in Lebanon, official statements in Beirut and Damascus do not reveal anything substantial about the incident. Israeli officials denied the claims.

As MEIB went to press, investigators had taken into custody the original owner of the Mercedes and were preparing to release sketches of two men who purchased the vehicle last year. However, as with previous bombings that have taken place in the country over the last decade, investigators are likely to ignore leads that point in the "wrong" direction, or simply manufacture evidence and torture detainees into making confessions that suit Syrian and Lebanese officials.

When a murder takes place (outside of the Middle East), investigators generally focus on suspects who 1) stand to gain from the victim's demise or consider themselves to have been severely wronged by the victim and 2) have the means to carry out the crime. It is important to keep both criteria in mind when reviewing the long list of suspects in Hobeika's assassination.

The most important piece of evidence is the fact that the assassination took place at Hobeika's residence in Hazmieh, an area which is heavily patrolled by Lebanese security forces because of its proximity to the Presidential Palace and the Defense Ministry, as well as the fact that many high-ranking military officers live there. It is also a major stronghold of Syrian intelligence. Planning an operation in this area would have been very difficult and risky unless the perpetrators had a go-ahead from Damascus. Any group acting without Syria's blessing would have found it much less complicated (though still difficult) to target Hobeika at his office in Sin al-Fil. Moreover, the road where the bombing took place was inaccessible up until this month due to extensive road work - meaning that the operation was planned quickly by people who had only recently decided to kill him.

The Suspects

The Israelis?

Since Israel has carried out similar assassinations of its enemies in Lebanon in the past (e.g. the January 1979 assassination of Abu Ali Hassan Salameh, the commander of Yasser Arafat's Force 17), it might have been able to carry out the assassination of Hobeika, either directly or through Lebanese proxies, even in an area like Hazmieh.

Contrary to widespread Arab and Western media speculation, however, Israel does not appear to have had a compelling motive to kill Hobeika, as there was no reason to believe that he would reveal credible new information about Israeli involvement in the massacre during his testimony in Belgium. His SLA story would not have been taken seriously enough to threaten Israel - in fact, the ridiculousness of the story would have undermined the credibility of the lawsuit. Indeed, the assassination worked against Israeli interests insofar as it allowed Hobeika's vague allegations of direct Israeli involvement to attract international media attention without being formally specified or cross-examined in a courtroom.

The Palestinians?

In light of the large numbers of Palestinians that Hobeika was responsible for killing during the war in Lebanon, the possibility that an armed Palestinian faction carried out the assassination cannot be discounted. Just last year, in fact, a senior official of Yasser Arafat's Fatah movement in Lebanon, Bassam Abu Sharif, threatened to kill Hobeika.5

Notwithstanding such boasts, assassinating Hobeika would not really have advanced Palestinian interests since he was already politically irrelevant. Moreover, Palestinians in Lebanon are extremely vulnerable and would have risked severe retaliation had they conducted such an operation without Syria's blessing and it was traced to a Palestinian faction. After the assassination, Fatah officials in Lebanon apparently feared that they might be blamed - they moved quickly to prevent any public celebrations in camps under their control and issued a decree prohibiting residents of Sabra and Shatila from speaking to journalists for a 48-hour period. "Emotionally, people may feel some relief from Hobeika's death," acknowledged a Fatah military bureau member in Lebanon, "but if you look at it from a political perspective, this is not a good thing for us."6

The Lebanese Forces

Another possible culprit is the radical wing of the LF. In 1991, according to the Lebanese authorities, LF operatives loyal to Samir Geagea carried out a 1991 bombing which destroyed Hobeika's car and killed one of his bodyguards. In June 1998, the Lebanese authorities claimed to have uncovered a plot by former LF intelligence operatives to assassinate Hobeika, as well as Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, the chief of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, and then-Interior Minister Michel Murr. The 13 alleged members of the cell who were arrested by security forces reportedly received their orders via the Internet from an LF office in Australia.

However, as the above failures illustrate, radical LF factions have been thoroughly penetrated by Lebanese and Syrian intelligence over the last ten years. It is highly unlikely that any anti-Syrian faction of the LF could have undertaken an operation of this complexity in Hazmieh unless it was coordinating with the Syrians - which seems unlikely.

Although a Western news agency in Cyprus received a fax claiming responsibility in the name of a previously unknown group called "Lebanese for a Free and Independent Lebanon," this was probably a ploy designed to implicate the anti-Syrian opposition.

It is possible that former LF officials currently aligned with the Syrians might have been motivated to assassinate Hobeika, fearing that he might speak candidly about their involvement in the Sabra and Shatila massacre, and received permission from the Syrians to do so. The fact that the Lebanese government's investigation of the massacre was suspended in 1983 suggests that there are politically sensitive details to the case that have not seen the light of day. However, while this remains an outside possibility, there are more plausible explanations.

The Syrians

As the final months of Hobeika's life clearly indicate, the Syrians had completely withdrawn their protection and instructed the Lebanese judiciary to take action against him, or at least threaten to do so. Given the timing of the judicial moves, it appears likely that the Syrian intelligence learned about his attempts to approach the CIA. Had the Syrians learned that he was considering leaving the country (which also appears likely, since his bodyguard was talking freely about it), they would have had a strong motive to eliminate him, or allow others to eliminate him, before he could do so.

Moreover, the Syrians stood to gain from the killing in other important ways. The event could serve as a pretext for a massive crackdown on opponents of the Syrian occupation in Lebanon. More generally, the assassination, which bore an uncanny resemblance to killings during the war, lent support to Syria's claim that a withdrawal of its forces from Lebanon would lead to internal violence and instability.

However, while it appears that Damascus wanted to see Hobeika dead and permitted the operation to occur in an area with a strong Syrian intelligence presence, it is not all that likely that they carried it out themselves - it would have been more expedient to simply facilitate an operation by a local group.

Hezbollah's Foreign Operations Branch (Imad Mughniyah)

As previously mentioned, Hezbollah's political leadership has its own grudge against Hobeika dating back to the March 1985 car bomb attack against Fadlallah, as does the movement's main external sponsor, Iran, for his role in the deaths of four Iranian diplomats during the civil war. A more immediate motive for eliminating Hobeika would have been the desire to preempt his assistance to the CIA in locating Imad Mughniyah, the head of Hezbollah's Foreign Operations Branch (jihaz al-amaliyyat al-kharijiyya).

Although Mughniyah's agency is no longer officially part of Hezbollah, this is mainly a facade designed to allow the group's political leadership to maintain plausible deniability regarding its operations. Logistically it is part of the same organization - the main distinction being that Mughniyah coordinates directly with Iran and Syria, and maintains a degree of operational autonomy.

While there is no direct evidence linking Mughniyah to the assassination, he had the most compelling motive of any suspect to order a hit on Hobeika, his operatives in Lebanon were clearly capable of such an operation, and the Syrians appear to have been more than willing to facilitate it.

Notes

1 Theodor Hanf, Coexistence in Wartime Lebanon: Decline of a State and Rise of a Nation (London: IB Tauris, 1993), p.307.

2 Robert M. Hatem, From Israel to Damascus: The Painful Road of Blood, Betrayal and Deception (La Mesa, CA: Pride International Publications).

3 The Independent (London), 26 January 2002.

4 Al-Sharq al-Awsat (London), 26 January 2002.

5 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 25 January 2002. After the assassination, Abu Sharif told the newspaper that "Sharon beat us to him."

6 The Daily Star (Beirut), 25 January 2002.