|

| Vol. 3 No. 12 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | December 2001 |

| | Dossier: Karim Pakradouni President of the Lebanese Phalange (Kata'ib) Party |

|

However, the Phalange party is no longer the preeminent Christian political institution that it once was and Pakradouni's victory was indicative not of consensus within the Christian community, but of discord and resignation. Indeed, his ascendance was facilitated by the Syrians and the military-security establishment in Lebanon as a means of eliminating the Phalange as a threat to Lebanese President Emile Lahoud.

Pakradouni remains politically relevant, not because of his position in the Phalange, but because of his willingness to sublet his intellect to Damascus for the time being. Although overt opposition to the Syrian occupation has rapidly spread throughout civil society in recent years, Pakradouni has distinguished himself as the most eloquent Christian advocate of Syrian hegemony in Lebanon.

Background

Karim Pakradouni was born in the Armenian district of Beirut, Bourj Hammoud, on August 18, 1944. His father, Minas Pakradounian, left Armenia in 1920 and settled in Aleppo, Syria. Several years later, he moved to Lebanon and married a Lebanese woman, Lour Shallita.

Karim received his secondary education at Notre Dame de Jamhour in the suburbs east of Beirut in the Baabda district and became politically active as a teenager, joining the Christian nationalist Phalange party in 1959. He continued his education at the University of St. Joseph, where he studied law, history and political science, and was elected head of the Phalange party's student organization in 1968. After graduating later that year, he married Mona al-Nashif, the niece of former MP, businessman and philanthropist Salem Abdelnour. Abdelnour provided Pakradouni with the financial security to forgo a career and concentrate on his political aspirations. In 1970, he was elected to the Phalange party politburo.

Pakradouni became a chief spokesman for the "Arabist" faction of the Phalange party, which believed that Christian economic interests, political power and cultural autonomy could best be preserved by appearing to embrace Arab nationalism, much as Syria's Alawite minority (and, to a lesser extent, its Druze and Christian minorities) had done under the rubric of Ba'athist ideology. Eager to shed his Armenian identity, he changed his name from "Pakradounian" to the somewhat more Arabic-sounding "Pakradouni" and gave Arabic names to his children, Jihad and Jawad.

Pakradouni developed close ties with the PLO and led a Phalange student delegation to Jordan to meet with Yasser Arafat in 1969. However, this association alienated many Christians, who saw the armed Palestinian presence in Lebanon as an unacceptable affront to Lebanese sovereignty. In 1973, Pakradouni's car was bombed a day after he accompanied Arafat on a drive through the streets of east Beirut - an operation, apparently by right-wing elements in the Phalange, designed not to kill Pakradouni (his car was vacant), but to warn him. He was targeted by a similar bomb attack in December 1976, but it exploded under his car 30 minutes after he had left it.

However, the primary focus of Pakradouni's "Arabism" was Syria. In 1972 he launched a dialogue in Damascus with the leadership of Syria's Ba'ath party, culminating the following year in a visit by Phalange party leader Pierre Gemayel to the Syrian capital to meet President Hafez Assad. After the outbreak of clashes between Christian militias and Palestinian factions in Lebanon in 1975, Pakradouni and fellow Phalange politburo member George Saade repeatedly visited Damascus to broker an agreement with the Syrian dictator, who had sent the Syrian-equipped Palestinian Liberation Army (PLA) into Lebanon against the Phalange.

During these visits, Pakradouni developed a friendship with Assad (he subsequently wrote a book which contained one of the most descriptive portrayals of the Syrian president) and prepared the ground for the intervention of Syrian military forces the following year - this time to prevent advances by the Palestinian-leftist coalition. Due in part to his rapport with Assad, Pakradouni was appointed as an advisor to Lebanese President Elias Sarkis shortly after his election in 1976.

The War Years

Pakradouni began to gravitate away from the Syrians after Phalange military commander Bashir Gemayel consolidated the various Christian militias under the banner of the Lebanese Forces (LF) during the late 1970s. After becoming the unchallenged leader of east Beirut, Gemayel now sought the presidency and in 1981 appointed Pakradouni to his political team in order to facilitate contacts with the Arab world.

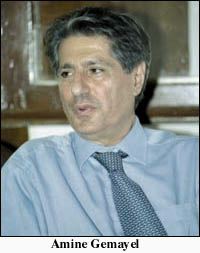

Shortly after being elected president by the Lebanese parliament in 1982, however, Bashir Gemayel was assassinated and Pakradouni's hopes of political advancement died with him. Although Bashir's brother, Amine, assumed the presidency, he did not offer Pakradouni a high-level appointment in his government. In the years that followed, Pakradouni jockeyed for power within the LF.

|

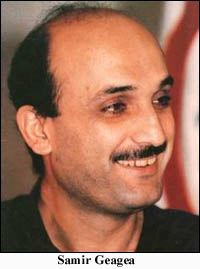

Pakradouni initially aligned himself with Hobeiqa, who proceeded to make a stunning political turnabout that was emblematic of militia politics during the war. Hobeiqa, who was until then a staunch advocate of LF ties to Israel and anathema to most Arabs for his lead role in the 1982 massacre of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, abruptly aligned himself with Damascus in hopes of reaching an accord with Syrian-backed militias and assuming the presidency in a Syrianized post-war republic. Pakradouni appeared in Damascus alongside Hobeiqa in December 1985 at the signing of the so-called Tripartite Accord, a Syrian-brokered agreement between the country's three top militias which would have legalized the Syrian presence in Lebanon. In the days that followed, however, Pakradouni abandoned Hobeiqa as Christian opposition to the accord intensified. In January 1986, LF forces loyal to Geagea quickly took control of east Beirut and Hobeiqa fled to France and later returned to Syrian-occupied territory.

After Hobeiqa's ouster, Pakradouni assumed the number two position in the LF behind Geagea. During this period, he was instrumental in cultivating a rapprochement between the LF and Yasser Arafat. In 1987, Pakradouni visited Tunisia to meet Arafat and negotiated a deal whereby the Palestinians paid $15 million to the LF and President Gemayel in return for the granting of Lebanese visas to five thousand PLO fighters, which allowed Arafat to reestablish an armed presence in the Palestinian refugee camps. This move dealt a major setback to both Israel, which had driven the PLO out of Beirut in 1982, and Syria, which had subsequently driven Arafat and his remaining loyalists out of north Lebanon.

Pakradouni appeared to have definitively moved away from accommodation with Syria. After a car bomb in east Beirut killed 20 people on May 30, 1988, Pakradouni publicly condemned Damascus for "striking at the last stronghold of freedom and independence."2 Moreover, Pakradouni was instrumental in brokering LF arms purchases from Syria's arch-rival, Iraq, during a series of trips to Baghdad, including a highly-publicized meeting with Iraqi President Saddam Hussein in September 1988. The Iraqis provided T-55 tanks, sophisticated rockets and other armaments (estimated to be worth over $30 million) to the LF, as well as training for LF commanders, significantly bolstering the militia's military defenses in the Christian enclave.

However, as always, Pakradouni was careful not to burn any bridges. Throughout the late 1980s, Pakradouni remained in contact with the Syrian regime, especially Vice-President Abdul Halim Khaddam. Pakradouni was also careful to cultivate ties with moderate Christians opposed to the LF's heavy-handed rule. When Geagea challenged the popular military government of Michel Aoun in 1989, Pakradouni openly condemned the move and left the country in protest, denouncing from abroad the LF's opposition to the restoration of government authority in east Beirut.

Post-war Politics

While Pakradouni did not back Geagea's controversial decision to back Syria's invasion of east Beirut and the ouster of Aoun in October 1990, he quickly accepted Syrian hegemony in Lebanon and sought to position himself as a primary interlocutor between the Syrians and the Christian community. However, Pakradouni was not regarded by the Syrians as a particularly attractive candidate for inclusion in the Lebanese government, as he was not from a prominent family and had no local base of political support. With little "value added" to bring to the table, Pakradouni sought to negotiate his way into power by making an intellectual contribution to Syrian interests in Lebanon and seizing leadership of the Phalange party.

Realizing that Syria's number one priority in Lebanon is preventing its government from either negotiating directly with Israel or reining in armed attacks on Israeli forces, Pakradouni established himself as one of the most eloquent purveyors of anti-Israeli polemics. His weekly articles in the London-based Arabic daily Al-Sharq al-Awsat have clearly inspired how Lebanese officials publicly justify their adherence to Syria's position regarding Israel.

Pakradouni has also adopted radical positions on other issues in order to prove his anti-Israeli and anti-Western credentials. In May 1997, he visited Khartoum and declared that Hassan Turabi, the spiritual leader of Sudan's notorious Islamist regime, "is struggling on behalf of all Arabs and Muslims." In July 2001, he visited Libya and filed a lawsuit (on behalf of Muammar Qaddafi's "World Organization for Benevolent Societies") in Belgium courts against Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon for the latter's (indirect) role in the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre.

Meanwhile, Pakradouni steadily expanded his influence in the Phalange party. This necessitated following the political rules of the game laid down by the Syrians while outmaneuvering rival contenders. The costs of violating Syrian rules while residing inside Lebanon were vividly illustrated by the fates of Geagea and Phalange politburo member Boutros Khawand. Despite a 1991 general amnesty for crimes committed during the war, Geagea was put on trial and sentenced to life in prison for ordering the murders of rival Christian leader Dany Chamoun and his family in 1990 and former LF member Elias Zayek in 1991. Khawand, who took a resolute stance against the Syrian occupation, was kidnapped in September 1992 and, according to Human Rights Watch, imprisoned in Syria.3

Pakradouni aligned himself with the party's president, George Saade, and vice-president, Mounir al-Hajj, who were committed to working within the system. Whereas most reputable Christian politicians boycotted the 1996 parliamentary elections because of blatant Syrian interference in the electoral process,4 Pakradouni and Saade competed in the elections and lost badly.

After Saade's death in November 1998, Pakradouni briefly campaigned for leadership of the party, but acquiesced to Hajj's succession in March 1999 and assumed the number two spot in the party's hierarchy. Hajj aligned the party even closer to Damascus and joined an electoral coalition with Interior Minister Michel Murr and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), but was humiliated after failing to win a parliamentary seat in the 2000 elections.

|

However, as Gemayel steadily overcame his initial reluctance to openly contest Syrian hegemony in Lebanon in the months that followed, Pakradouni made a stunning about face and began arguing that the return of a political heavyweight to the helm of the Phalange would not benefit the Christian community. "The Phalange party is not a monopoly for any one person, family or religion," he declared in July 2001. "We need to organize the party's internal structure whereby its existence does not depend on a single person but on national destiny."6

Pakradouni's turnabout was reportedly the result of blackmail by President Emile Lahoud, whose political base in the north Metn would be threatened by Gemayel's ascendancy, and the Syrians, who have consistently backed Lahoud in his vendettas with other Christian politicians. As Geagea's imprisonment demonstrated, Damascus could selectively lift the 1991 amnesty to punish former militia leaders who overstepped Syrian red lines in Lebanon. Having served as Geagea's deputy during the war, Pakradouni has been particularly susceptible to such threats. Official Lebanese sources quoted anonymously by the press have, on occasion, hinted at prosecuting Pakradouni on murder charges dating back to 1987, when he presided over the ad hoc trial and execution of two men who had attempted to assassinate him.

Another skeleton in Pakradouni's closet that has been used by the authorities to control him is his past ties with the Israelis. In May 1999, Lebanon's military court filed charges against Pakradouni for visiting Haifa in 1987 and 1988 to meet with Israeli officials, a capital offense under Lebanese law. After the Lebanese Bar Association categorically rejected the court's request to lift Pakradouni's immunity from prosecution (which applies to all lawyers under Lebanese law), there was intense speculation as to whether the authorities would seek to overturn the decision before a special Appeals Court in the weeks that followed. During this period, Pakradouni met with a host of Syria's top allies in Lebanon in an effort to derail the prosecution. Although it is not clear what, if any, explicit assurances Pakradouni may have given them, his efforts appeared to ward off the threat of prosecution for the time being. Speaking to reporters after meeting with Pakradouni in early June, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri declared that the case against Pakradouni "affects national unity and as such is against the interests of the presidency, Syria and the resistance [to Israel]."7 Critically, however, the case against Pakradouni remained in conspicuous limbo, as the authorities did not formally close the investigation. The threat of prosecution continued to hang over his head, ready to materialize suddenly in the event that he alienates the Syrians.

When Lebanese security forces launched a massive arrest sweep against anti-Syrian activists in August 2001, Pakradouni was one of the few Christian political figures outside of the government to back the crackdown. Parroting Syrian propaganda, he wrote in his weekly column that opposition to the Syrian presence in Lebanon is "related directly or indirectly to American and Israeli pressure."8

Fearing that Gemayel would most likely win a majority of votes in the Phalange congress (al-Hay'a al-Nakhiba), Pakradouni and Hajj stacked the deck in the congress by reducing the representation of Metn (Gemayel's home district) in the congress and appointing opponents of Gemayel to fill vacant seats. In addition, in August 2001 they managed to persuade 13 of the Phalange politburo's 25 members to move the date of the elections forward from the Spring of 2002 to October, giving Gemayel less time to mobilize support for his candidacy. Afterwards, Gemayel angrily announced that he would boycott the election and mobilized his supporters to openly demonstrate against Pakradouni.

Fearing that his election would be a hollow victory unless Gemayel acknowledged the validity of the elections, Pakradouni and his backers in the regime resorted to threats and intimidation against the former Lebanese president. In mid-September, Lebanese security forces disrupted a gathering of around 1,000 pro-Gemayel demonstrators and detained 40 people. On September 19, Pakradouni announced that the authorities had resumed an investigation into accusations that Gemayel embezzled millions of dollars during his tenure in office and that Lebanese Prosecutor-General Adnan Addoum might summon him for questioning.

Pakradouni easily won the October 4 election, but Gemayel has repeatedly denounced the new Phalange president-elect as an imposter and vowed to regain control over the party. Pakradouni, for his part, has vowed to take legal action if Gemayel continues to organize political activities in the name of the Phalange party.

However, as long as Syrian troops remain in Lebanon, Pakradouni's political future rests less on the outcome of his feud with Gemayel than on his subservience to Damascus. In mid-October, he told a Beirut newspaper that "calling for a Syrian withdrawal is stupid," adding that "Syria entered Lebanon for regional reasons, and is not going to leave because of Lebanese reasons."9 Moreover, amid heavy American pressure on the Syrian and Lebanese regimes to halt Hezbollah attacks against Israeli forces in the disputed Shebaa Farms area since September 11, Pakradouni has met frequently with senior Hezbollah officials and reiterated his unqualified support for the continuation of armed operations against the Jewish state.

As for the future of the political party he now heads, within hours of his election, Pakradouni declared that the Phalange "shall be the party of the president, the army and the judiciary."10 This slogan, which has been repeated frequently, is revealing - these are the three governmental institutions most heavily controlled by the Syrians and farthest removed from the electoral process.

Notes

1 Al-Thawra (Damascus), 10 November 1984.

2 United Press International, 30 May 1988.

3 See The Methodology of Enforced Disappearances in Lebanon, Human Rights Watch, 1997. For an analysis of Syrian kidnappings in Lebanon, see Gary C. Gambill, Syria and the Politics of Arbitrary Detention in Lebanon, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, January 2001.

4 Gary C. Gambill and Elie Abou Aoun, How Syria Orchestrates Lebanon's Elections, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, August 2000.

5 The Daily Star (Beirut), 28 September 2000.

6 Al-Diyar (Beirut), 22 July 2001.

7 Al-Safir (Beirut), 4 June 1999.

8 Al-Sharq al-Awsat (London), 25 August 2001.

9 The Daily Star (Beirut), 22 October 2001.

10 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 5 October 2001.