|

| Vol. 3 No. 11 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | November 2001 |

|

Notwithstanding their general predilection for categorizing the international community of states with such catch phrases as "rogue state," American officials have long maintained an ambivalent stance toward Syria. The US State Department has continued to include Syria in its annual list of states sponsoring terrorism, a classification which prohibits American economic assistance (or support for multilateral economic assistance), blocks the sale of military equipment, and heavily controls the sale of "dual-use" equipment to Damascus. Yet, in its most recent annual survey of state terrorism sponsors, the State Department commends Syria for maintaining a "longstanding ban" on supporting terrorist attacks against "Western targets" (a phrase which is apparently interpreted to exclude American tourists periodically killed by Syrian-backed Palestinian groups). Moreover, while successive American administrations have frequently repeated the official mantra of support for a Lebanon "free of all foreign forces," they have tacitly backed the continued presence of Syria's military forces in the country in hopes of securing its approval of a comprehensive peace settlement with Israel.

This ambivalence is rooted in a core set of assumptions that frame the conventional wisdom among mainstream Washington insiders. First, Syria has long been seen as holding the key to a comprehensive settlement of the Arab-Israeli conflict (a truism which dates back to the 1970s adage that, for the Arabs, there can be "no war [against Israel] without Egypt and no peace without Syria") and, to varying degrees, other objectives of American policy in the Arab world (e.g. containment of Iraq). Second, the Syrian regime is believed to be eminently "rational", which in the American lexicon means that its leadership is responsive to external incentives (and disincentives) and abides by commitments once they are made. The 1990-91 Gulf crisis is typically cited as the paradigmatic illustration of the latter - in return for the Bush administration's tacit approval of its October 1990 military occupation of Beirut,2 Damascus joined the American-led coalition against Iraq and, shortly thereafter, the American-sponsored peace process.

However, in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States, President Bush warned that "there is no neutral ground" in the American war on terrorism. "If any government sponsors the outlaws and killers of innocents, they have become outlaws and murderers themselves. They will take that lonely path at their own peril." The Bush administration (and its British counterpart) has launched an ambitious effort to force the Syrians to choose, once and for all, whether to join the ranks of American allies in the region or be isolated as a "rogue state."

Bush administration officials believe that Damascus can contribute to the war on terror in three main ways: intelligence sharing, diplomatic support, and bolstering the peace process by ending its support of extremist groups who violently oppose accommodation with Israel.

While there are some indications that Damascus may have provided intelligence information to the United States, the Syrian regime has not only declined to publicly support the American "war on terror," but has repeatedly sought to undermine its legitimacy. Moreover, it is abundantly clear that Syrian President Bashar Assad will not or cannot reduce Syrian support for extremist groups that have offices in Damascus and training camps in neighboring Lebanon.

Intelligence-Sharing

Syria is seen by Western officials has a particularly promising source of intelligence information for two reasons. First, Syrian intelligence agencies devote considerable resources to monitoring the activities of Syrian Islamists, both at home and abroad, who are affiliated with the Syrian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood and its radical offshoots. Some of these activists are believed to have established ties with the al-Qa'ida terrorist network. For example, a Syrian-born businessman in Germany, Mamoun Darkazanli, reportedly controlled a Hamburg bank account believed to belong to one of the founders of al-Qa'ida and, according to German law enforcement officials, met with one of the hijackers, Marwan al-Shehhi, several times.

Second, in an effort to isolate its own Islamist dissidents, Damascus has long maintained ties with Islamist groups operating in other Arab countries. In particular, Syria's close ties to the Palestinian Islamist groups Hamas and Islamic Jihad, as well as various Lebanese Islamist groups based in north Lebanon, may have yielded a considerable amount of valuable intelligence on al-Qa'ida.

According to a report in the New York Times, a senior CIA official traveled to Damascus in October and met with Syrian intelligence officials to discuss the US investigation of al-Qa'ida. The unnamed official was reported to have been from the Directorate of Operations, the CIA's clandestine espionage department. Although the nature of the discussions is not known, the meeting itself was characterized by the paper as "represent[ing] a significant shift in relations between the United States and Syria.3

There have also been unconfirmed reports of other meetings between US and Syrian intelligence personnel. According to the London based daily Al-Zaman, American intelligence officials met with Iranian and Syrian counterparts in Ankara in October.4 In addition, there have been reports (repeatedly denied by the Syrian government) that an FBI delegation recently visited the Syrian city of Aleppo. The hijacker's ringleader, Muhammad Atta, traveled to the city at least twice in the 1990s.

The Diplomatic Front

American officials recognized early on that building support in the Arab world for the war on terror would be much more difficult than it was for war against Iraq in 1991. Nearly all Arab states have a substantial Islamist opposition that draws support from a significant segment of the population. While Syrian backing for Operation Desert Storm was considered essential by US officials in 1991, it has been considered critical in 2001. However, while the late Hafez Assad astonished the world by unequivocally backing the American-led coalition against Iraq in 1991, his son and successor has balked at aligning his regime squarely behind the US-led war on terror.

Initially, prospects for Syrian diplomatic support looked promising. Following the September 11 attacks, Assad sent a message to President Bush, pledging to help the US "eradicate terrorism in all its forms." Moreover, the Syrian regime took special precautions to ensure that no pro-bin Laden demonstrations were held on its soil.

However, it soon became clear that unqualified diplomatic support from the Syrian regime would not be forthcoming. On October 3, Syria's ambassador to the UN, Mikhail Wehbe, declared during his speech before the General Assembly that Damascus recognized "the right of the United States, within the framework of the United Nations, to pursue the perpetrators of these terrorist attacks and to bring them to justice," but added that "any action to this end must be accompanied by irrefutable proof and in-depth and clear investigation."

|

This claim was echoed by Syria's state-appointed Islamic leader, Grand Mufti Ahmad Kaftaro, who said during a sermon that "Western sources are talking about an implication of [the] Mossad" in the attacks.6

The Syrian media has parroted the same conspiracy theory, publishing a relentless stream of reports claiming that either Israeli or American intelligence services masterminded the attacks. The state-run Al-Thawra newspaper suggested on September 18 that the Mossad "sought to shake the United States and the world, upon directives from [Israeli Prime Minister] Ariel Sharon who wants to divert attention away from his aggressive plot, and link the attacks to the Arabs, the Muslims, and Osama bin Laden." The state-run Al-Baath newspaper said on September 20 that it had "intelligence indicating some sort of relationship between the Mossad and the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington." The next day, Radio Damascus reported that Israel may have planned the attack to "push America into a war" against Arabs.

Strangely, the state-run English-language daily Syria Times went much farther than its Arabic counterparts. On September 19, the paper stated without any hint of equivocation that 4,000 Jewish employees of the World Trade Center stayed home on instructions from the Israeli government, calling this "irrefutable evidence that Sharon and his ilk are responsible for such a big tragedy that befell the American people," and claimed that Israeli leaders once threatened to "burn Washington" if Clinton did not meet Zionist demands. In an October 8 editorial, the paper suggested that the attacks were "related to a party that has strong connection with the high US echelons of the CIA and other allied secret services, such as the Mossad."

|

In recent weeks, even Assad himself has begun to explicitly condemn the war in Afghanistan. This was particularly evident during British Prime Minister Tony Blair's visit to Damascus late last month. During the joint press conference following their talks, Assad launched a verbal tirade that stunned the British premier and won applause from Syrian reporters in attendance. "We cannot accept what we see on television, the killing of innocent civilians, hundreds dying now every day," said Assad. While repeating his condemnation of the September 11 attacks, Assad added, "We didn't say we support the international coalition for launching war." Much as Assad used the visit of the Pope in May to launch a scathing, anti-semitic diatribe intended to impress public opinion in the Arab world, the young Syrian leader felt obliged to prove his anti-Western credentials by embarrassing the first British prime minister ever to visit Syria (and, judging from the reaction of the British press, probably the last).

Syrian Sponsorship of Extremist Groups

The third aim of American policy toward Damascus since September 11 has been to bring about a reduction in Syrian sponsorship of militant guerrilla and terrorist groups opposed to the peace process. Five Palestinian extremist groups that the US State Department considers terrorist organizations are headquartered in Damascus: the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Islamic Jihad, Fatah al-Intifada, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC) and Hamas. In addition, Syria facilitates Iranian arms shipments to the Lebanese Hezbollah movement through Damascus International Airport and has the final authority over its military operations.

Initially, the United States strictly limited the scope of its anti-terror campaign to the al-Qa'ida terror network. On September 24, President Bush signed an executive order mandating sanctions against any state or financial institution in the world that does business with 27 groups and individuals tied to Bin Laden. Although Hezbollah and Syrian-sponsored Palestinian groups were included in the State Department's October 5 update of its list of foreign terrorist organizations, this merely restated an existing designation and imposed no new sanctions.

It appears that this hands off policy stemmed from a quid pro quo: the US would not explicitly target Syrian-sponsored extremist groups in its "war on terror" so long as Damascus acted to restrain its surrogates from launching violent provocations against Israel, which would complicate American efforts to secure Arab backing for the war in Afghanistan. This quid pro quo was most evident with respect to Hezbollah. The US ambassador in Beirut, Vincent Battle, repeatedly emphasized that Hezbollah was not a target of the American campaign.

However, Assad appears to have interpreted this concession as a sign of weakness. "The Americans need the Arab and Islamic countries in order to forge the American coalition [against al-Qa'ida]," he boasted before a meeting of leaders from Hezbollah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, the PFLP, and the PFLP-GC in late September. "Following the September 11 explosions, the US has not demanded anything. On the contrary, the lists of organizations designated as terrorist was changed [and] the names of organizations and forces resisting the Israeli occupation were omitted."8

Not surprisingly, the agreement was short-lived. On October 3, Hezbollah guerrillas launched their first operation in three months against Israeli forces in the disputed Shebaa Farms area. Meanwhile, it became clear that Damascus was not restraining extremist Palestinian factions when the PFLP launched an unprecedented assassination of an Israeli cabinet minister on October 17.

The American hands off policy was soon rescinded. On October 18, the American ambassador in Damascus demanded that the Syrians take immediate action against the PFLP.9 However, whereas Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Authority (PA) immediately outlawed the PFLP's military wing and arrested several of its members, the Syrian regime did nothing.

When Hezbollah launched a second attack against Israeli forces on October 22, the US response was immediate. The following day, President Bush called the movement a terrorist group of "global reach" during a meeting with Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres.10

The Bush administration, already under pressure from Congress to expand the war on terrorism to include anti-Israeli groups, attempted once more to bring Syria into the fold. British Prime Minister Tony Blair attempted to win a new commitment from the Syrians to rein in extremist groups during his visit to Damascus the following week, but was apparently unsuccessful - in the press conference that followed, Assad went out of his way to compare Hezbollah and Palestinian extremist groups to the French resistance against the Nazis.

On November 3, the Bush administration added Hezbollah, the PFLP, Islamic Jihad, the PFLP-GC, and Hamas to the September 24 "priority list" of terrorist organizations, threatening sanctions against foreign banks that decline to freeze their assets. Although administration officials hastened to add privately that the new list did not signify a broad policy shift, a change in the tone of American public statements concerning Syria was soon evident. "Terrorism is terrorism," Secretary of State Colin Powell told the Syrian foreign minister during their talks in New York on November 11, adding that the US "will not ignore this kind of activity that is sponsored or supported by Syria or finds a safe haven in Syria."11

Although American officials have yet to clarify exactly what measures, if any, will be taken against Syria, they have alluded quite clearly to what the consequences will be for Lebanon if it refuses to take action against Hezbollah. In a November 11 interview on ABC, US National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice warned Lebanon that its refusal to cooperate could jeopardize its "integration into the world economy" and even put its economic "survival" at risk. According to Lebanese sources, the US has raised the question of cutting the $35 million in annual aid provided to Lebanon and threatened to "torpedo" plans to organize an international donor conference to raise financial assistance for Lebanon's moribund economy.

Although Syria's relatively closed economy makes it somewhat less susceptible to US economic pressure, sustained pressure on Lebanon could threaten the Syrian regime by weakening its control of Lebanon. Hezbollah's attacks against Israeli forces in the Shebaa Farms area have met with widespread criticism in Lebanon, because they are seen as advancing Syria's interests at the expense of Lebanese national interests.12 Even Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri has publicly called into question the wisdom of Hezbollah attacks.

Conclusion

The difference between 1990 and 2001 may have less to do with Syrian intentions than with Syrian leadership. The late President Hafez Assad's grip on power was so absolute that he could make dramatic foreign policy reversals by fiat and force his regime to accept them without suffering serious repercussions at home. His son and successor, Bashar, who is probably more innately sympathetic to the West than his father, appears to have no such autonomy. Unable to assert his authority over the military-security apparatus of the regime, Bashar Assad fears that openly cooperating with Washington will undermine his tenuous position.

|

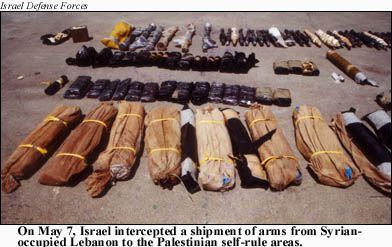

In May 2001, an Israeli coastal patrol intercepted a Lebanese-registered ship carrying a large shipment of weapons, including Katyusha rockets and surface-to-air missiles, that had departed from Syrian-occupied northern Lebanon.13 According to Israeli officials, two members of the PFLP-GC who were arrested in August while planning a car bomb attack against the 49-story Azrieli tower in Tel Aviv were trained in Damascus.14 In September, Israel's Shin Bet intelligence agency uncovered an extensive network of Hamas terrorists in the West Bank that had been recruited and supervised by the Hamas office in Damascus. Most of the 20 members of the network detained by Israeli security forces did not join the movement through its local branches, but were recruited by the Damascus office while studying at universities in Syria and other Arab states. They were subsequently sent for military training in Syria, Iran and Lebanon.15

Now that the Bush administration is determined to get the peace process back on track, it is not likely that there will be a return to business as usual with Syria. Secretary Powell and others in the administration who argued that Assad would be responsive to the prospect of improved relations with America have been discredited. Prominent figures in the administration who have advocated a get tough policy with Syria and even held out the prospect of military force, such as Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul D. Wolfowitz, Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, and Vice President Dick Cheney's chief of staff, I. Lewis Libby, may now have their turn.16

Notes

1 This was noted in a broadcast of CNN's Crossfire by co-host Tucker Carlson, quoting from an advance copy of an article that appeared in The New York Times Magazine on October 7.

2 An advisor to Elias Hrawi, the president of Lebanon's pro-Syrian government in West Beirut, paraphrased the US message authorizing Syria's overthrow of a rival anti-Syrian regime based in East Beirut as follows: "If the battle is prolonged, we will have to express our regret over the continued violence in Lebanon. If you fail, we will not condemn the action but call on the Lebanese to resort to dialogue to sort out their differences . . . Israel will not interfere as long as Syria does not approach south Lebanon or threaten [Israel's] security interests." See "US Agreed Not to Block Move By Syria on Aoun, Lebanon Says," The Washington Post, 16 October 1990.

3 "CIA Is Said to Have Sought Help From Syria," The New York Times, 30 October 2001.

4 Al-Zaman (London), 21 October 2001.

5 Reuters, 17 October 2001.

6 Agence France Presse, 21 September 2001.

7 Agence France Presse, 18 November 2001.

8 Al-Hayat (London), 28 September 2001.

9 Al-Safir (Beirut), 19 October 2001.

10 The Jerusalem Post, 24 October 2001.

11 Agence France Presse, 18 November 2001.

12 On April 14, Hezbollah launched an attack on the Shebaa Farms area which killed an Israeli soldier. The following day, Hariri's newspaper, Al-Mustaqbal, questioned "whether Lebanon, under the circumstances it faces nowadays, can bear the consequences of such an operation and its political, economic and social impacts."

13 See Syrian Provocations Go Unanswered, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, May 2001.

14 Agence France Presse, 21 September 2001.

15 Voice of Israel (Jerusalem), 30 September 2001; Israel TV Channel 1 (Jerusalem), 30 September 2001.

16 On September 20, the New York Times reported that Wolfowitz and Libby are "pressing for the earliest and broadest military campaign against not only the Osama bin Laden network in Afghanistan, but also against other suspected terrorist bases in . . . Lebanon's Beqaa region," an area controlled by the Syrian military. Armitage declared on October 11, "I don't consider Syria part of the coalition [against terrorism]." When asked what American policy should be toward countries that do not meet Washington's expectations, Armitage stated that "it runs the gamut from isolation to financial investigations, all the way up through possibly military action." Reuters, 11 October 2001.