|

| Vol. 3 No. 9 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | September 2001 |

The detention of a eleven Syrian opposition figures, including two members of parliament, over the last month seems to suggest that the Syrian regime has come full circle since the death of Hafez Assad in June 2000.

During the first six months of his tenure, Syrian President Bashar Assad permitted the country's once-vibrant civil society to rematerialize as academics, businessmen, writers, and even political ideologues began openly meeting to discuss the many problems facing the country. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, the notorious Mezze prison was shut down, and the government even allowed the establishment of a private newspaper. The birth of a new post-authoritarian political order seemed to be on the not-too-distant horizon.

While the military-intelligence apparatus that shares power with the young Syrian president suddenly and capriciously brought this wave of political liberalization to a halt seven months ago [see Dark Days Ahead for Syria's Liberal Reformers in the February 2001 issue of MEIB], most observers continued to maintain that a decisive break had been made with the past. Although periodic abductions and incommunicado detentions by the security forces continued [see Continuing Detentions and Disappearances in Syria in the June 2001 issue of MEIB], the mukhabarat did not go so far as to target major public figures. The leaders of Syria's burgeoning reform movement were often subjected to threats and intimidation, but never the jail house.

In recent months, however, the reform movement began to display a degree of coordination and unity of purpose that greatly disturbed the security barons of the regime. Ideological divisions, a defining element of Syrian civil society during its heyday under the parliamentary system of the 1950s, appeared to recede. Leftists and pro-capitalist reformers, unified perhaps by the realization that a resurgence of authoritarianism would not discriminate among dissidents, began to coalesce under the banner of human rights and democracy. Even the Muslim Brotherhood began opening channels with the reform movement.

Wagering that increasing tensions with Israel would sufficiently distract public opinion, both locally and internationally, the security forces swiftly arrested the leading lights of Syria's reform movement.

The Arrests

The first target of the crackdown was Damascus MP Mamoun al-Humsi, who has been regarded with suspicion since establishing a parliamentary human rights commission several months ago. The final straw came early last month, when he began a hunger strike to protest "official corruption and the massive powers wielded by the security forces." On August 9, he was arrested and taken by the security forces to Adra Prison, while several of his relatives were interrogated by the authorities. Humsi has been officially charged with tax fraud, but government sources have alluded to his involvement with "foreign quarters," suggesting that further indictments are likely which could carry sentences of up to 15 years imprisonment.

|

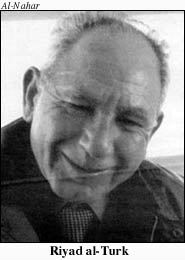

On September 1, the authorities arrested Riyad al-Turk, 71, the head of the Communist Party Political Bureau (CPPB). Just weeks beforehand, Turk had made his first major public appearance since being released from prison in 1998 after more than 17 years in captivity. Speaking at a meeting of the socialist Jamal al-Atassi forum on August 5, the aging communist scathingly criticized Syria's "hereditary republic" and called for a transition from "despotism and tyranny."

The following day, a lawyer for Nizar Nayyouf, who has been in Paris for medical treatment, announced that the dissident journalist had been indicted on charges of publishing false news reports, inciting sectarian strife and seeking to illegally change the constitution. Needless to say, Nayyouf, who spent nine years in prison before being released earlier this year, has not returned to Syria.

|

On the evening of September 8, two Syrian doctors who had attended Sayf's forum were arrested by the authorities. Kamal al-Labwani, 44, was reportedly lured from his house by security officers who requested that he examine a patient. Walid al-Bunni, 38, was arrested at his home in Damascus.

On September 9, three other activists who attended the forum were arrested. Arif Dalila, a prominent economist and pioneering leader of the civil society movement, was seized by security forces after publicly denouncing the crackdown. Habib Saleh, a businessman, and Hassan Saadoun, a school teacher, were also arrested.

On September 12, Syrian authorities arrested Sayf's lawyer, Habib Issa, 55, after he gave an interview on Qatar's Al-Jazeera satellite television defending his client. Later that day, opposition activist Fawaz Tello was also arrested. Issa and Tello were both members of the founding board of the Syrian Human Rights Society.

Political Implications

The security establishment clearly anticipated that the arrests of so many leading dissidents would cast a pall of fear over the country and silence those who had been fortunate enough to be spared their fate. However, each arrest has been openly condemned by leading reform activists and the country's fledgling human rights organizations.

The president of the Committees for the Defense of Human Rights in Syria, Akram Ne'eitha (himself a former political prisoner) accused the state of "crossing all red lines in dealing with the peaceful opposition." Haitham Maleh, the head of the Human Rights Society in Syria, did not hesitate to publicly denounce the "serial arrests" in a fax to the Associated Press, despite the fact that two leading members of the group had been taken into custody (a clear indication that he could have been next in line).

Although several international human rights groups registered firm objections to the arrests, international reaction to the arrests was initially rather muted. Indeed, some have suggested that the low key international response to the Lebanese regime's crackdown on anti-Syrian dissidents in August [see Lebanon's Shadow Government Takes Charge in the August 2001 issue of MEIB] was interpreted by the Syrians as a green light to silence dissent at home. However, on September 28 the European Union issued a belated statement calling for the immediate release of the detainees. The letter, conveyed to Foreign Minister Farouk al-Shara, urged Syria to "respect human rights, freedom of speech and dialogue." The EU emphasized that its complaint was not an attempt to interfere in Syrian affairs, but was merely "advice" to facilitate Syria's economic partnership with the EU. In reaction, the Syrian Foreign Ministry stated that the matter was a "a purely domestic affair."

Although economic reform has stalled [see The Political Obstacles to Economic Reform in Syria in the July 2001 issue of MEIB] and Bashar Assad's initial moves to expand civil liberties have been definitively overruled by the security chiefs, it is likely that the country's resurgent civil society will continue to press for change. The emerging alliance between the business community and intellectuals of all stripes cannot be totally crushed without dramatically undermining the regime's efforts to attract international investment. Many reformers are cognizant of this limitation faced by the security chiefs and remain cautiously optimistic that that they will eventually prevail.

Notes

1 Al-Hayat (London), 6 September 2001.

2 Tishrin (Damascus), 8 September 2001.