|

| Vol. 3 No. 9 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | September 2001 |

In the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, American officials have declared a policy of zero tolerance toward governments that continue to harbor terrorist organizations in general, and Osama bin Laden's Al-Qa'ida network in particular. Attention has been focused primarily on Afghanistan, where bin Laden's operatives maintain an open presence under the protection of the ruling Taliban. The regime in Afghanistan is not, however, the only government to turn a blind eye toward the activities of militant Islamists associated with bin Laden.

In Lebanon, occupying Syrian forces continue to allow terror organizations linked to bin Laden to recruit and train followers in Palestinian refugee camps, which Lebanese security forces have been banned from entering, as well as the eastern Beqaa Valley and areas of northern Lebanon, which remain heavily occupied by Syrian army units.

According to the New York Times, senior administration officials such as Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul D. Wolfowitz and Vice President Dick Cheney's chief of staff, I. Lewis Libby, are "pressing for the earliest and broadest military campaign against not only the Osama bin Laden network in Afghanistan, but also against other suspected terrorist bases in . . . Lebanon's Beqaa region."1 According to Lebanese media reports, a team of American intelligence officials is expected to arrive in Beirut in the coming weeks to investigate terror networks in the country linked to bin Laden. US officials have already sent Beirut a list of 27 Lebanese suspected of having links to Al-Qa'ida.

Imad Mughniyah

|

Mughniyah, operating directly on behalf of Iranian intelligence, was responsible for planning suicide bombing attacks on the US embassy in Lebanon and the Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983. In addition, he masterminded the 1985 hijacking of a TWA airliner to Beirut, the kidnapping of Americans in Lebanon during the 1980s, and the bombings of Israeli targets in Argentina. He is currently under indictment in the US, which has offered a $2 million reward for information leading to his arrest.

Over the last fifteen years, Mughniyah has successfully eluded several attempts by US special forces to capture him. In 1995, an American team was planning to seize him during a stop-over in Saudi Arabia on his flight from Sudan to Syria, but the Saudi authorities aborted the operation by refusing to permit the aircraft to land.

To the chagrin of American officials, Mughniyah continued to freely enter Lebanon after Syrian forces completed their conquest of the country in October 1990. Under Syrian protection, Mughniyah has reportedly continued to operate several training camps in the Beqaa Valley, though he himself is believed to reside in Iran most of the time. It is rumored that he has undergone extensive plastic surgery in order to alter his appearance.

Mughniyah's contacts with bin Laden reportedly began around seven years ago. Last year, one of bin Laden's top aides who was indicted for involvement in the 1998 bombings of the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, Ali A. Mohamed, testified before a Manhattan court that he had been in charge of making security arrangements for a meeting between bin Laden and Mughniyah in Sudan during the early 1990s to discuss ways of opposing American hegemony in the Middle East. Indeed, Mughniyah's successful use of terrorism to drive American peacekeeping troops out of Lebanon in the 1980s is said to have been a major inspiration for bin Laden.

In June 1996, Iran's Ministry of Information and Security hosted a meeting of terrorist leaders in Teheran that included Mughniyah and a senior aide to bin Laden. Since then, senior operatives of bin Laden's terror network have met several times with Mughniyah.

Mughniyah's involvement in the September 11 terrorist attacks is strongly suspected by American intelligence officials. Although no hard evidence of this has been revealed publicly, there have been unconfirmed reports that Mughniyah made several secret trips to Germany in recent years - suggesting that he may have met with perpetrators of the attacks, a number of whom lived in Germany prior to infiltrating American soil.

The main reason why officials are focusing on Mughniyah is that he has considerable experience with hijackings. In addition to his role in the TWA hijacking mentioned above, Mughniyah is believed to have been involved in planning the hijacking of India Air Flight IC814 on Christimas Eve, 1999. This flight, much like the four that were hijacked in the United States, was seized by terrorists wielding knives and scissors who had enough flight training to take control of the cockpit. Another similarity is that the hijackers of the Air India flight stabbed a passenger and forced the others to watch him bleed to death - this was also done on most, if not all, of the four American airliners in order to terrify the hostages into passivity. The 1994 hijacking of a Kuwaiti airliner (which then flew to Iran, where Mughniyah himself "negotiated" the release of the hostages) also bore this similarity.

Usbat al-Ansar

According to informed US and Lebanese sources, Mughniyah's collaboration with bin Laden has occurred mainly in conjunction with Usbat al-Ansar (The League of Supporters), a militant Palestinian Sunni Islamist group operating primarily in the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp in the southern Lebanese port of Sidon and, according to some reports, the Nahr al-Bared camp in northern Lebanon.

The founder of the group, Hisham Shreidi, was once a senior leader of Al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya (The Islamic Association) during the war-torn1980s. Al-Jama'a, an urban-based Sunni fundamentalist movement operating mainly in Tripoli, Sidon and Akkar, advocated the establishment of an Islamic political order and called for holy war (al-jihad al-muqaddas) against modern day "crusaders" such as Israel and Lebanon's Christian communities. While Shreidi was renowned for his efforts in fighting Israeli forces in south Lebanon, his active participation in fighting against the Amal movement of Nabih Berri in 1986 led Al-Jama'a to expel him from the organization. After this, Shreidi established Usbat al-Ansar. In 1991, Shreidi was assassinated on the orders of Amin Kayid, the commander of Yasser Arafat's Fatah movement in Ain al-Hilweh.

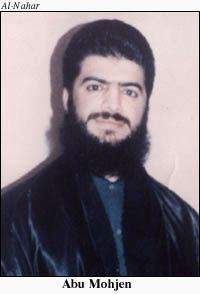

|

During the 1990s, aside from sporadic attacks on liquor stores and religious sites, Abu Mohjen focused the group's struggle mainly against rival Palestinian and Islamist groups operating in and around Sidon. In 1995, the group assassinated Nizar al-Halabi, the leader of Al-Ahbash, an "Islamist" group employed by Syrian intelligence to co-opt Islamic fundamentalists. Three members of the group were subsequently executed for their role in the killing and Abu Mohjen was sentenced to death in absentia for ordering the assassination.

Strangely, Lebanon's Syrian-installed government permitted over 4,000 mourners, many wielding assault weapons and all chanting anti-government slogans, to gather in Mazraa for the funeral of the three executed assassins. Stranger still, the Syrians refused to allow Lebanese security forces to enter Ain al-Hilweh and arrest Abu Mohjen. In May 1999, Abu Mohjen took revenge for the death of Shreidi by assassinating Kayid and his wife. The following month, the group took revenge for the 1997 executions by killing four Lebanese judges. Despite the palpable wave of outrage that swept Lebanon, Syria's veto remained in place.

According to American officials, bin Laden began providing the group with considerable financing during the late 1990s. Moreover, under the auspices of Usbat al-Ansar, dozens of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were sent to bin Laden's training camps in Afghanistan.

Whether bin Laden's financing caused a shift in the group's objectives, or vice versa, is unclear, but during the last few years Usbat al-Ansar has assumed a more international orientation. For example, many of its resources have been directed toward assisting Muslim rebels in Chechnya against the Russians, rather than against more proximate enemies such as Israel. In January 2000, a member of Usbat al-Ansar, Ahmad Raja Abu Kharrub (alias Abu Ubeida), launched a rocket-propelled grenade attack against the Russian embassy in Beirut, killing a security guard and wounding several others. On the same day, suspected members of the group launched a grenade attack against a Lebanese army checkpoint near Ain al-Hilweh that wounded a Lebanese soldier. The following week, four suspected members of the group, disguised as soldiers, attempted to launch another attack on the Russian embassy, but the plot was foiled by security forces.

Moreover, Abu Mohjen has been linked to the January 2000 revolt by a shadowy group of rebels that received financing from bin Laden's terror network (see below).

Since Abu Mohjen has avoided making public appearances in recent years, his precise role within the group is less clear today. Publicly, at least, his brother Abu Tarek and assistant Abu Obeida appear to be in charge now. Local press reports have cited anonymous security sources as saying that Abu Mohjen has left Lebanon and taken refuge in an unspecified African country, but these leaks are probably inspired by the Syrian regime's effort to avoid being held accountable for his actions (much like the Taliban, who claim to be unaware of bin Laden's whereabouts and frequently suggest that he has left the country).

"Takfir wa al-Hijra"

|

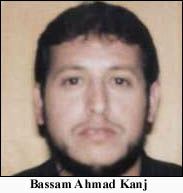

The Lebanese-born leader of the group who was killed in the fighting, Bassam Ahmad Kanj (alias Abu A'isha) and many of its members had fought alongside bin Laden in Afghanistan against occupying Soviet forces in the 1980s. According to local press reports, Kanj came to the US in 1985 on a scholarship from the Hariri Foundation and subsequently married an American woman, Marlene Earl, who converted to Islam. After becoming involved in fundraising activities for the Afghani Mujahidin, Kanj and his wife went to Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1988 to assist the effort more directly. During his stay in Peshawar, Kanj met several figures who would later form the nucleus of the group: Jamil Hammoud (alias Samir Abu Durr), Bassim (Sheikh Samir), Hilal Jaafar (Tarek), Ahmad al-Kassam (executed later in Lebanon for the killing of Sheikh Nizar al-Halabi, the leader of the rival al-Ahbash group), and Khalil Akkawi (Ahmad).

Kanj returned to the US the following year. During the 1990s, he lived and worked as a cab driver in Boston. It is known that, during this period, he was close friends with fellow cab driver Raed Hijazi, who was later indicted for involvement in a series of foiled bombing plots by a bin Laden cell in Jordan that were timed to coincide with the turn of the millennium. Two of the suspected hijackers who flew on separate flights out of Boston on September 11, Ahmad al-Ghamdi and Satam al-Suqami, have been tied by federal investigators to Raed Hijazi.

After making at least one trip back to Lebanon during the interim, Kanj returned to his homeland for good in 1996 and established Takfir wa al-Hijra. The group was divided into three regional branches: The north Lebanon branch was headed by Kanj himself; the Beirut branch was headed by Akkawi; and the Beqaa branch was headed by Kasim Daher, whom Kanj met while attending the 1995 International Islamic Conference in Chicago, Illinois. Daher, who traveled repeatedly to Afghanistan during the late 1980s, was a close associate of Sheikh Omar Abdul Rahman, who is now serving a life sentence for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing (Daher was detained by the Canadian police on suspicion of involvement in the bombing, but was released in 1998).

According to Lebanese media reports, Kanj received financial support from overseas associates of bin Laden through bank accounts in Beirut and north Lebanon.3 Court documents from judicial proceedings against captured members of the group listed the names (or, perhaps, aliases) of the primary figures involved, including Haroun al-Yamani (Panama), Shawki Muhammad (Austria), Abou Katada (Britain) and Abdul Bari al-Khaligi (United Arab Emirates).

Most of the money was used to buy weaponry for the group from the Palestinian camps and from the followers of the rebellious Subhi al-Tufeili, a former head of Hezbollah. Abu Mohjen was later indicted for his role in transporting the arms from Ain al-Hilweh by sea to Kanj's bases. Camps were established in the rural Dinniyeh district of North Lebanon to train the followers, both militarily and ideologically, for their failed attempt to establish an Islamic "mini-state" as a stepping stone to taking control over all of Lebanon.

American officials have already requested permission to interview many of the captured rebels who are currently held in Lebanon's Roumieh prison.

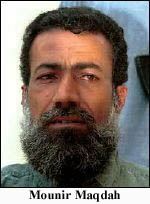

Mounir Maqdah

|

In September, Maqdah was convicted in absentia and sentenced to death. However, despite persistent Jordanian requests for his extradition, Damascus has refused to allow Lebanese security forces to enter the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp and arrest Maqdah.

How Maqdah and other fringe elements of the Fatah movement in Lebanon were recruited to work for bin Laden remains unclear, but it is possible that Mughniyah was involved. Prior to the establishment of Hezbollah in the early 1980s, Mughniyah served as one of Yasser Arafat's bodyguards.

Conclusion

To some extent, bin Laden's influence in Lebanon is a reflection of the increasing salience of Sunni Islamist movements throughout the Middle East. Usbat al-Ansar is certainly an indigenous manifestation of a broader trend taking place in other Arab countries. What is unique about bin Laden's influence in Lebanon is that it has appeared to evolve with the tacit approval of Syria and its satellite regime in Beirut.

Put simply, Syria has demonstrated a remarkable ability to infiltrate, uncover, and eliminate underground dissident movements in Lebanon, much as it has in Syria itself. To the extent that the above groups and persons have been able to operate freely in Lebanon, it is because Syria has permitted them to do so. The massive amounts of weaponry accumulated by the Tafkir wa al-Hijra rebels and their training camps in the mountains east of Tripoli, for example, could not have escaped the attention of Syrian intelligence. That Abu Mohjen and other suspected terrorists in Ain al-Hilweh have not been arrested despite outstanding warrants for their arrest is a conspicuous case of Syrian interference.

This is not to say that the Syrian regime endorses their ideology or objectives. The secular Ba'ath regime in Damascus has no affinity for Islamist ideology and has brutally repressed Islamist movements at home. They are allowed to operate above the law in Lebanon because their presence is seen by Damascus as a valuable hedge against domestic and international pressure to withdraw from the country.

In discussions with Western diplomats, Syrian officials frequently claim that the withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon will result in an outburst of civil war (the implication being that, just as the civil war during 1980s provided a safe haven for anti-American terror groups, future civil unrest in Lebanon will provide an outlet for extremists to organize attacks against the US). But this claim is only credible so long as bona fide terrorist groups continue to operate in what the Lebanese call "pockets of insecurity." Usbat al-Ansar and other extremist groups will seize upon the withdrawal of Syrian forces, the reasoning goes, and create chaos throughout the country.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The 60,000 strong Lebanese army is more than capable of maintaining security throughout the country after a Syrian withdrawal (unless, as many Lebanese expect, Damascus covertly arms these groups so as to provide a pretext for the return of Syrian military forces). At the very least, the Lebanese army is cabable of moving into these "pockets of insecurity." But Syria will not allow it.

On the day after the terrorist attacks in America, Syrian President Bashar Assad sent a message to President George W. Bush, pledging to help the US "eradicate terrorism in all its forms." On September 17, a senior State Department official said that the Bush administration is waiting to see what action Syria takes against groups that may have links to bin Laden. "If they are willing to take steps against the perpetrators of this act [on September 11], it will be useful to have them with us," the official said.5 Whether this indeed will be the case remains to be seen.

Notes

1 New York Times, 20 September 2001.

2 The Times (London), 17 September 2001.

3 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 5 January 2000.

4 United Press International, 29 March 2000.

5 Agence France Presse, 18 September 2001.