|

| Vol. 3 No. 7 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | July 2001 |

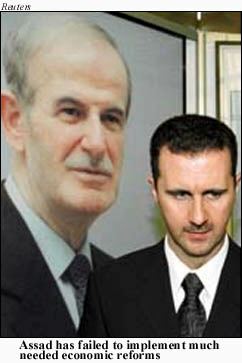

Just over one year ago, Syrian President Bashar Assad inherited control over one of the poorest countries in the Middle East (per capita GNP being a mere $1010 in 1999), saddled by one of the highest rates of annual population growth in the region (2.7%), negative economic growth (-1.7% in 1999), skyrocketing unemployment (estimated at 20%), a negative balance of trade, and dwindling oil reserves (2.5 billion barrels). That the Syrian economy was in dire need of sweeping reforms was widely acknowledged even in the state-run press.

|

Nevertheless, it is evident from Bashar's first year in power that the obstacles to economic liberalization are mainly political. Free market reforms would not only run counter to the proclaimed socialist goals of the ruling Ba'ath party, but would undermine the regime's fragile base of social support. Whereas Sadat quickly moved to "capitalize" the ideology of the Egyptian regime and politically mobilize sectors of the population that stood to gain from economic reforms, Assad has proven to be incapable of either.

The Political Economy of Structural Adjustment

Most transitions from statist to market economies that have taken place around the world in recent years have been preceded by economic crises that dramatically undermined the state's ability to secure the continued support of its elite coalition and/or key sectors of the population at large. Under such conditions, authoritarian regimes have been driven to promote economic reform as a means of attracting foreign investment and acquiring debt-relief loans and other subsidies from the international community,

Economic liberalization generates a new set of "winners" and "losers." Under the old system, the winners include those who benefit from government subsidies and employment in the government bureaucracy or state-run economic enterprises, as well as elites who profit from institutional corruption. Under the new system, the winners are those who benefit from a transparent, free market economic system. Of course, many of the winners under the old system have a great deal to lose if substantial economic liberalization is undertaken. Authoritarian regimes that undertake major free-market reforms must therefore build a stable coalition of support for economic reform by mobilizing those who stand to gain from capitalist development, while either sidelining or appeasing those who stand to lose from liberal economic reforms and have the resources to obstruct change.

Economic liberalization usually necessitates some form of political liberalization for several reasons. First, the regime itself has incentives to provide some kind of political opening. Not only must the regime co-opt beneficiaries of structural reforms who were hitherto excluded from the decision-making process, but it must also compensate for its loss of control over the economy, which weakens the networks of elite patronage that hold the regime together. Second, economic liberalization generates pressure for more political liberties within society. Increasing the proportion of economic resources in private hands strengthens the bargaining power of citizens as a whole. In particular, a vibrant private sector economy generates demands for greater political participation from the business community, which has a direct stake in increasing government accountability. Moreover, economic liberalization in the 21st century virtually requires a modern telecommunications infrastructure and the free flow of information, eroding the walls of ignorance that authoritarian regimes (particularly Syria's) have historically built to suppress dissent.

Many have pointed to the so-called "China model" as an exception to this trend - rapid economic liberalization is said to have proceeded in the absence of substantial political liberalization. However, as George Gilboy and Eric Heginbotham point out in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, even in China economic liberalization has been accompanied by an expansion of political liberties and independent social organizations are increasingly permitted to actively represent their interests:

Chinese farmers are organizing to protest corrupt officials . . . Chinese consumers frequently speak out and organize against defective products, financial scams, and official corruption . . . some industry leaders have coalesced to force the central government to change policies on taxes, international trade, and price reforms . . . A variety of special interest groups, ranging from environmental and animal-rights activists to regional soccer clubs (which are sometimes prone to hooliganism), now place new demands on the state for resources and attention.1The case of China is an exception which proves the rule: even a strong, stable authoritarian regime must permit modest, controlled openings of political space as economic liberalization advances.

The Social Foundations of the Syrian Regime

In order to put in context the pace of economic and political liberalization in Syria, it is necessary to first identify the "winners" that benefited from the statist economic system put in place by the ruling Ba'ath party. Until the early 1960's, the Syrian political system was dominated by the predominantly Sunni Muslim landed aristocracy and urban bourgeoisie. After the Ba'ath party's seizure of power in 1963, sweeping land reform emasculated the former, while the regime's nationalization of industries, establishment of state-run retail and marketing networks, price fixing and virtual monopolization of foreign and wholesale trade disinherited the latter. In the decades that followed, the Syrian state forged a foundation of social support comprised of four partially overlapping constituencies.

The first consists of a stratum of senior Alawite military officers and predominantly Sunni merchants who have been co-opted by the state. Members of this "military-mercantile complex" have used their connections with the regime to amass illicit wealth and have come to dominate private-sector industry, real estate, agriculture, tourism and transportation.

The second core social base of support is the minority Alawite community as a whole (and, to an extent, other non-Sunni minorities). The Alawites, members of an offshoot sect of Shi'ite Islam, constitute about 12% of the population, concentrated mainly in rural areas of the coastal governorates of Latakia and Tartous. Alawite living conditions lagged far behind those of the majority Sunni population prior to the Ba'athist seizure of power. During the 1960's, political power increasingly gravitated toward Alawite military officers, particularly after Hafez Assad's ascension to the presidency in 1970. Over the last thirty years, Alawite living conditions have dramatically improved relative to the Sunni majority.2

The third group comprises workers and professionals who rely upon public sector employment. An estimated 1.2 million Syrians are employed by the military, civilian bureaucracy and state-run economic enterprises, accounting for 40% of the national workforce.

The fourth social constituency consists of rural peasants who benefited from land reform measures undertaken by the Assad regime and remain dependent on the state for access to credit and input subsidies. Over 80% of Syrians employed in the agricultural sector are members of state-run agricultural cooperatives and unions. Since Alawite and other minorities constitute a greater percentage of the rural population than Sunnis, this category overlaps considerably with the first. Indeed, Assad and many other Alawite members of the regime were of peasant extraction.

Although all of the social groups mentioned above have some stake in the current system, the last two do not pose special obstacles to economic reform. Strictly speaking, Syrian peasants have the least to lose from economic liberalization. Since the agricultural sector in Syria is largely privatized anyway, their stake in the system is confined to the continuation of state subsidies. Indeed, insofar as economic liberalization bolsters growth in the economy as a whole, it is arguably in the interests of the peasantry.

Public sector workers and bureaucrats clearly would not benefit from privatization of the Syrian economy in the short term. Indeed, Bashar Assad has repeatedly stated that substantial privatization is not an option due to the influx of 150,000-200,000 people into the job market each year. However, public sector wages have deteriorated considerably over the last two decades, so the stake that this social group has in the system has diminished. Moreover, public sector employees would benefit from measures to root out the rampant corruption that has diminished productivity.

Bashar and the Military-Mercantile Complex

It is the military-mercantile complex that has the most unequivocal and direct stake in preventing substantial economic reforms. For example, the Syrian government's reluctance to completely eliminate foreign currency exchange restrictions is largely due to the fact that political elites have profited enormously from Syria's skewed exchange rate system. The Syrian regime banned foreign currency decades ago and has since overvalued the lira. This has permitted figures with close connections to the regime to buy dollars from state banks at the official exchange rate and then sell them for a profit at the open-market rate.

Entrenched elite interests have also undermined efforts to reform the banking sector. During the last forty years, the state monopolized banking and government lending institutions tended to approve loans and set interest rates on the basis of political considerations, rather than the credit-worthiness of the recipient. No serious reform of the state banking sector has been undertaken (in fact, Bashar's uncle, Muhammad Makhlouf, is still a Central Bank administrator). In January 2001, the regime issued a decree permitting domestic and foreign investors to open private banks, ostensibly ending the state's monopoly. However, the law required either that Syrian nationals or companies own at least 51% of newly established banks or that the Syrian government own 25% of the shares. Moreover, the Syrian government has refused to establish an independent regulatory body. As a result, as of May no foreign banks had applied to enter the Syrian market (with the exception of Lebanese banks, which are influenced by Syria's continuing military and political control over its capital-rich neighbor).

Syria's outmoded custom regulations are another area where elite interests have blocked reform. Syria has one of the highest custom rates in the world, yet the government's customs revenue is very small. The amount of money skimmed off by corrupt officials before it reaches the treasury has been estimated at $1 billion per year. In some cases, customs regulations are specifically tailored to enrich well-connected elites. Tobacco imports are banned, for example, precisely because figures close to the regime profit from smuggling cigarettes into the country. Imports of a variety of other consumer goods are prohibited outside of the so-called "free zone," an enclave in Damascus managed by two of Bashar's maternal cousins, Rami and Ihab Makhlouf. Not surprisingly, the government has not made any significant efforts to reform the customs system.

The most highly-publicized aspect of economic reform in Syria has been the so-called "anti-corruption campaign" launched by Bashar several months prior to his father's death. However, this campaign has merely targeted political figures considered to be a threat to Bashar's succession and replaced them with reliable allies. Systemic corruption is still rampant in Syria. It is not considered a conflict of interest, for example, that the current Minister for Economic Affairs, Dr. Muhammad al-Imadi, owns a textile factory and is involved in other commercial ventures.

The Syrian regime's reluctance to undertake reforms that might threaten elite privileges is also evident in its relationship with the European Investment Bank (EIB), which has allocated 182 million euros for a variety of projects ranging from banking to civil service reform. However, only 1 million euros have been spent by the Syrian regime, apparently due to fears that the EIB will require an audit or otherwise expose systemic corruption. A senior European Union official recently warned that "after a few years, these projects will be canceled and the funds transferred to other countries."3

The Alawite Community

The Alawite community's stake in the current economic system has been the subject of much debate. Although some scholars have insisted that Alawites have received a disproportionate share of state development funds, this appears to be true only insofar as all rural communities benefited from government efforts to modernize the countryside.4 For the majority of Syrian Alawites, the material benefits of structural reforms would arguably exceed the costs. Insofar as Syrian Alawites oppose economic liberalization, it is for political, not material, reasons. Economic liberalization would bolster the economic power of the traditional Sunni bourgeoisie and effectively re-enfranchise this class politically. This, in turn, would endanger Alawite control of the regime.

It is for this reason that, contrary to his rhetoric, Bashar has exhibited intense mistrust toward the bourgeoisie, whose skills and entrepreneurial experience would otherwise be important assets in a modern economy. According to one informed observer, "the state has not consulted the country's legal and economic experts" in its economic reform plans, "and when experts have volunteered their services to the government, . . . they have been ignored."5

Alawite concerns also explain why Bashar has allowed capital from the Arab Gulf states to flow freely into the tourism sector. Hundreds of millions of dollars have poured into the construction of hotels and other accommodations along the heavily Alawite coastal governorate of Latakia. In addition, the Syrian ministry of tourism has spent at least $100 million dollars constructing and renovating hotels, building roads to major historical sites, and other tourism-related projects. Not only does this flow of investment directly benefit the Alawite community by creating jobs and increasing property values, but more importantly it strives to establish the tourism industry as the backbone of the Syrian economy. This would serve as a powerful bargaining chip for Syrian Alawites in the event that a Sunni-led regime takes power - the tremendous economic costs of unrest in Latakia would deter Sunni oppression of the Alawite community.

Political Paralysis

In short, Bashar Assad's efforts to reform the Syrian economy have been strictly conditioned by an unwillingness to fundamentally transform the regime's social base of support. In Egypt, economic reforms were accompanied by substantial, though heavily controlled, political openings designed to weaken opponents of reform and empower potential "winners" in a liberalized economic system. In order to garner support from this new constellation of social forces, the Egyptian government reinvented itself. Socialist elites were sidelined as Western-trained economists were brought into government to guide the economic transition and the regime made a clear ideological commitment to a liberal economic order.

Bashar Assad's failure to undertake substantial economic reforms is therefore rooted in his failure to effect a controlled political opening. Early on, the new Syrian president made it clear that political reforms at the institutional level would not be forthcoming. Despite considerable speculation that he would dispense with his father's practice of claiming an absurdly high percentage of the votes in presidential elections, Assad ostensibly received 99.7% of the valid ballots cast in Syria's July 11 presidential referendum (or 97.3% of all ballots). In his inauguration speech, he warned that Syria should not apply "the democracy of others," but rather a democracy that "springs from our own history, culture and personality, as well as the needs of our society and the requirements of our reality." He then declared that the National Progressive Front (NPF), a government organ established by his father that is comprised of handpicked delegates representing the ruling Ba'ath party and other leftist organizations, to be "a democratic model developed through our own experience" and pledged to "develop the Front's working formula . . . on all levels."

Nevertheless, during the first six months of his tenure, Assad introduced a number of limited political reforms. In November, the regime released over 600 political prisoners, declared a general amnesty and closed the notorious Mazzeh prison [See Bashar Breaks with the Past . . . Gradually in the December 2000 issue of MEIB]. In addition, many dissidents who had been fired from their jobs in state-run media and educational institutions were reinstated. More importantly, the new Syrian president presided over a dramatic reduction in the Syrian regime's restrictions on public discourse. Loose networks of Syrian intellectuals and businessman, most notably the Committees for the Revival of Civil Society (Lijan Ihya al-Mujtama' al-Madani), were permitted to organize publicly and express new ideas about pressing economic and political problems facing the country.

Initially, Assad strove to co-opt the movement and mobilize its activities in support of economic reforms. According to Ibrahim Humaydi, the Damascus correspondent of Al-Hayat, there was an undeclared "alliance" in the making between the civil society activists and Assad's reformist faction within the Syrian government, an alignment intended to strengthen Assad's position against hard-line members of the military mercantile complex who opposed economic (and political) liberalization.6 One Syrian official quoted by Al-Hayat directly acknowledged as much, stressing the need to "support reform . . . so as not to give those who oppose reform the chance to hamper this process."7

Assad also took a number of modest steps to liberalize the Syrian media. Mahmud Salama, a prominent trade unionist and critic of the government's economic policies, was appointed editor of the state-run Al-Thawra newspaper and Khalaf Muhammad al-Jarad, a researcher at the Center for Strategic Studies, was appointed editor of the state-run Tishrin newspaper. Both were instructed by Assad to permit the publication of a broader array of viewpoints. Meanwhile, Assad met with several reformers affiliated with the committees and informed them that they were welcome to criticize the state on economic matters so long as they did so exclusively in the state-run Syrian press. The government also permitted three political parties in the ruling Progressive National Front to publish their own newspapers and even allowed the establishment of the country's first independent paper, Al-Doumari, a satirical weekly published by the well-known political cartoonist Ali Farzat.

However, there were early signs of fierce opposition to Bashar's political opening among the hardline Alawite security establishment. In September, the Beirut-based newspaper Al-Muharrir (owned by a Syrian national, Nihad al-Ghadri, with close connections to Syrian intelligence) quoting a senior government official as saying that the civil society activists sought to "legitimize" subversion of the Syrian regime. Moreover, the security forces continued to employ extra-judicial measures of eliminating real or perceived threats to the state, apparently without authorization from Assad [see Continuing Detentions and Disappearances in Syria in the June 2001 issue of MEIB].

|

On January 29, Syrian Information Minister Adnan Omran launched a fierce diatribe against the civil society committees, warning that civil society is an "American term" which had recently been given "additional meanings" by "groups that seek to become (political) parties," an apparent reference to Sawwan and Sayf. "Each society has its red lines. Political freedom has red lines. Social freedom has red lines. Cultural freedom has red lines," he warned.8 Less than twenty-four hours later, Syrian novelist Nabil Suleiman was attacked by two unidentified assailants in the coastal city of Latakia, a stronghold of minority Alawite support for the regime. Suleiman, a prominent organizer of the civil society committees, was hospitalized with cuts on his head, face, and chest. Most civil society activists were convinced that hard-line figures in the regime were behind the assault [see Dark Days Ahead for Syria's Liberal Reformers in the February 2001 issue of MEIB].

In early February, Assad reiterated Omran's warnings to the reformist camp in very explicit terms. "When the consequences of an action affect the stability of the homeland, there are two possibilities: either the perpetrator is a foreign agent acting on behalf of an outside power, or else he is a simple person acting unintentionally," he told Al-Sharq Al-Awsat. "But in both cases a service is being done to the country's enemies, and consequently both are dealt with in a similar fashion, irrespective of their intentions or motives."9 As if to underscore his seriousness, Parliament Speaker Abd al-Qadir Qaddurah filed charges against Sayf for advocating a position opposed to the Ba'ath party and "violating the constitution."

Meanwhile, the regime launched an intensive public relations campaign, organized by Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam, to discredit the civil society movement. On February 18, they were accused of "forgetting the national and pan-Arab role performed by Syria" on state-run television. By February 20, the accusations had grown more serious as television broadcasts condemned "individuals and groups [who] have recently put forward issues that aim to harm Syria's reputation, role and status."

As a result of this intensifying atmosphere of intimidation, even Michel Kilo, a prominent leader of the civil society movement who had praised Assad's "broad-mindedness" in January, threw in the towel and announced that he was resigning from the movement in protest of a climate in which "a great number of Syrian intellectuals are being targeted by an intensified media campaign carried out by high-ranking party and government officials, who are falsely accusing them of being foreign agents and collaborating with the Zionists." The statement added somberly that "the mission of the founding committee for reviving civil society is nearing the end."10

Meanwhile, the regime issued regulations stipulating that those who wish to organize political forums must submit a formal application specifying the topic of the debate, the speakers, and the attendees. Initially, the regulations were used to prohibit anti-socialist forums from meeting, but over the next few months the state increasingly blocked applications by leftist groups. On April 29, for example, the Jamal al-Atassi Forum, a loose coalition of Nasserite intellectuals, had its request to hold a "General Conference of Intellectual Forum Organizers" turned down.

The Syrian government also ended its limited experiment with a free press. Salama, who had published a wide variety of viewpoints, including some editorials by prominent civil society activists, in the state-run Al-Thawra newspaper, was fired in May. The regime imposed strict censorship on the independent Al-Doumari newspaper, causing its circulation to slip from 70,000 to around 17,000 as its began more and more to reflect the government line. Nevertheless, Al-Doumari still managed to run afoul of the regime. On June 14, security forces told the newspaper's staff to stop printing its forthcoming issue, objecting to two pages which criticized the slow pace of economic reforms. The authorities "warned me that the newspaper would definitely be banned if we published the two pages," said Farzat, who complied and published a censored version of the issue, with the two offending pages left blank.11

It is no coincidence that the Syrian regime's limited experiment with political liberalization was derailed amid heightened regional tensions stemming from the Palestinian uprising that began in September 2000 and the subsequent election of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. Members of the "old guard" within the Syrian regime have not hesitated to justify the suppression of dissent on national security grounds or accuse liberal reformers of collaborating with Israel. Israel's April 16 air strike on a Syrian radar station in Lebanon was "a gift for the Syrian old guard," said one prominent Syrian reformer. "The return of a foreign enemy has let them take full control of the regime."12

Conclusion

Substantial economic reforms in Syria would likely fracture elite cohesion within the regime and jeopardize its tenuous base of social support, while a controlled political opening designed to garner support from the beneficiaries of capitalist development does not appear to be possible so long as the Alawite security establishment retains considerable autonomy from the president. Until Assad acquires full control over his regime, the pace of economic reform will be limited.

Fortunately for Bashar, fortuitous economic developments during the last year have mitigated his failure to undertake significant economic reforms and thus reduced societal pressure on the regime. Syria has managed to attract a modest level of investment from the Arab Gulf states. However, this inflow of capital has clearly been driven by political considerations, rather than by confidence in the Syrian economy. In July 2000, four Saudi firms established a holding company with a preliminary capital of $100 million to invest in Syria. However, the general-director of the company, Bashar Dardari, openly acknowledged at the time that the four Saudi groups "could secure larger profits if they invest in other places in the world." The desire of the Gulf states to shore up the Syrian regime may give it a brief respite from its inability to attract foreign investment, but only temporarily.

The year 2000 also witnessed an extremely abundant agricultural harvest and rising oil prices. In addition, late last year Syria began importing over 100,000 barrels of oil from Iraq at below-market prices in violation of UN sanctions against Baghdad (the oil is used for domestic consumption, allowing Damascus to increase its oil exports). Both, of course, offer only temporary relief (the former resulted from the vicissitudes of climate, while the latter derives from Western tolerance that is unlikely to continue indefinitely) and must be measured against the long-term decay of Syria's agricultural sector and diminishing oil reserves.

Notes

1 George Gilboy and Eric Heginbotham, "China's Coming Transformation," Foreign Affairs (Vol. 80, No. 4), July/August 2001, pp. 31-33.

2 The dramatic improvement of Alawite living conditions during Assad's thirty-year reign is illustrated, for example, by the fact that the percentage of households equipped with running water in the predominantly (75%) Alawite governorate of Latakia increased from 10% to over 70% between 1970 and 1985.

3 The Daily Star (Beirut), 2 July 2001.

4 "Although it is beyond question that Asad's power base is at its core solidly Alawi," writes Hanna Batatu in his widely-acclaimed study of contemporary Syrian politics, "there is at the same time little evidence that in his economic policies Asad gave a marked preference to the interests of the Alawi community, or that the majority of Alawis enjoy more of the amenities of life than the majority of the Syrian people." See Hanna Batatu, Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 229.

5 Middle East International, 4 May 2001.

6 Al-Hayat (London), 19 January 2001.

7 Al-Hayat (London), 14 January 2001.

8 Al-Hayat (London), 30 January 2001.

9 Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), 9 February 2001.

10 United Press International, 21 February 2001.

11 Agence France Press, 17 June 2001.

12 The Telegraph (London), 19 April 2001.