|

| Vol. 3 No. 5 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | May 2001 |

| Blanca Madani is the founder and president of the World Algeria Action Coalition (WAAC), a representative to the United Nations for the Amazigh under the Tazzla Institute for Cultural Diversity, an active member of the Amazigh Cultural Association of America (ACAA) and a co-editor of its publication, The Amazigh Voice. |

|

However, the demonstrators were not Islamists, but inhabitants of Kabylia, a strongly secular, predominantly Amazigh (Berber) region of Algeria. And the violent altercations were anything but routine.

While the killing of 19-year-old Guermouh Massinissa on April 22 by the gendarmerie1 was hardly an unusual occurrence, the ten days of riots in which at least 60 Kabyle youths were killed, and the sheer magnitude of popular resistance to authority now taking place in the region are anything but commonplace in Algeria, or for that matter, in the Middle East.

The scope and intensity of the revolt in Kabylia derive in part from the Algerian state's suppression of Amazigh identity and language. But even a cursory examination of the slogans, recriminations and demands of the people demonstrates that this is not the whole story, and perhaps not even the main plot. The high unemployment rate and pauperization of the population as a whole has long been part of daily life in this resource-rich country. An explosion was unavoidable, and Kabylia, the most densely-populated area of the country, was the most predisposed demographically and politically to this eventuality. State suppression of Amazigh identity and language combined with the common ingredients of poverty, social malignancy, oppression and corruption, prepared the fuse, which was ignited by the murder of an innocent teenager.

State Suppression of Amazigh (Berber) Identity

This article refers to the Tamzight-speaking population as Amazigh, rather than the commonly-used term Berber, since the former is the term used within the community itself (the latter is a Western expression derived from the Greek word for "foreigner"). The Amazigh people, believed to have originated in the Siwa Oasis in Egypt, have existed in North Africa for over 5,000 years, concentrated mainly in Morocco and Algeria, where they constitute a majority of the population in the Kabylia region.

The history of conflict between Kabylia and the central government in Algeria dates back to the French colonial period. The political and cultural dominance of the pied noirs was most heavily contested in the Kabylia region, which produced many famous martyrs in the Algerian war for independence (e.g. Abane Ramdane, Krim Belkacem, Ali Mecili). Hocine Ait-Ahmed is considered one of the "founding fathers" of Algeria. In addition, many sons of Kabylia living in exile in Europe were instrumental in initiating financing, and actively participating in the movements that led to independence (Etoile Nord-Africaine, PPA-MTLD, FLN, etc.).

After the war ended in 1963, Ait-Ahmed established the country's first post-independence opposition movement, the Socialist Forces Front (FFS), which opposed the one-party dictatorship of President Ahmed Ben Bella. In retaliation, Algeria's first president sent the army on a punitive mission in Kabylia, the violence surpassing, according to some testimonials, "anything ever done by the French."

In the years that followed, the new Algerian state proved to be nearly as intolerant of cultural pluralism as the colonial system it replaced. The "Arabization" process, later formalized into law in July 1998, mandated that the one and only officially recognized language in Algeria be modern standard Arabic - a language not understood by a large percentage of the population (the official Arabic literacy rate is 68%). Courts do not provide translators and all legal documents must be signed in Arabic.

Unity meant, and is still taught to mean, homogeneity - identification with Arab ethnicity and Islam. To the extent that Berber heritage is recognized at all, it is portrayed as part of a traditional, nostalgic past. Any discussion of Amazigh identity or public mention of ancient and legendary Amazigh heroes were prohibited prior to the 1980's as an offense against the unity of the Algerian nation.

In the mid-1970's, a soccer team from Kabylia, Jeunese Sportive Kabylie (JSK) had to change its name to Jeunese Sportive Kawkabi, since regional identity, particularly to Kabylia, was prohibited (it has since reverted to its original name). In 1980, local authorities canceled a conference on old Amazigh poetry by Mouloud Mammeri at the University of Tizi-Ouzou. Demonstrations against the authorities culminated in the tragic events of April 20, with tens of dead and hundreds injured. This came to be known as the "Amazigh Spring," an event that is commemorated every year. It was during this year's commemoration that the latest tragedy hit Kabylia.

The PouvoirWhile state suppression of Amazigh identity clearly conditioned the events in Kablyle, the scale of the revolt and the extent to which it is garnering support from Algerian society at large has much more to do with the specific form of authoritarian governance that continues to prevail in Algeria today. This system is based on a mafia network, headed not by the President and congress, but by a group of high-ranking military officers, collectively referred to as the pouvoir (the power) or "the generals," who have amassed enormous wealth through an extended patronage network.

The "hunger" riots of October 1988, which began in Algiers and quickly spread to other major cities, shook the very foundations of the Algerian political system. The popularity of the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) had been on the decline for several years, due to the economic problems of the country and the older generation's unwillingness to share or relinquish power to a younger generation, but the deaths of over 500 people after the military was called in to stop the demonstrations left the political establishment woefully bereft of popular legitimacy. In response, then-President Benjedid moved to politically liberalize the system. A new constitution was approved, permitting the formation of independent organizations, including political parties. The FLN relinquished its position as the country's sole political party. There were early signs that the military establishment would set limits to political liberalization in Algeria. When the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) called for a general demonstration in Algiers in June 1991, the military clamped down to "restore law and order." Nevertheless, the country's first multi-party elections got off to a promising start.

|

|

Virtually all newspapers in Algeria are owned or controlled by one of the mafia leaders: Nouvelle Republique by Gen. Nezzar; Al Acil by Gen. Mohamed Betchine; El Watan by Gen. Mohamed Lamari; Jeune Independant, El Khabar, and Quotidien d'Oran by the head of military security, Gen. Mohamed Mediene (a.k.a. Tewfik); and Liberté by a wealthy businessman close to Tewfik. While these papers have at times published criticisms of government officials and do present some differing views, they do not generally harm the generals themselves, focusing instead on the president and ministers. When a general has been targeted in the past, it has often been a manifestation of divisions among the pouvoir.2 The recent criticism of generals found among some journalists, however, might be more directly due to the scale and intensity of recent developments (the rebellion in Kabylia, criticism by the international community, etc.) rather than a schism among the generals.

Algeria's current president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, could not have been elected without support from the mafia leaders. His principle backer was the powerful Maj. Gen. Larbi Belkheir, who served as interior minister during Benjedid's presidency and was one of the chief members of the High Security Council that forced Benjedid's resignation in 1992. Belkheir was at the center of much activity prior to the election, swarmed by visitors, and exchanging numerous calls, including overseas, as those seeking favors or beholden to him awaited his decision, and markers were called in to support the general's choice once it was confirmed.

Inside Algeria, rampant poverty has created citizens who are thoroughly dependent on favors from local mafia bosses. Those who try to set up their own business are soon "visited" by mafia thugs who clearly spell out the terms of survival. If the aspiring entrepreneur resists, one of two things will happen: either he will soon find himself without a business (after it is burnt to the ground), or the business will find itself without an owner (after he is killed and buried).

Once beholden to the mafia, it is difficult to extricate oneself. Individuals can flee into exile, but their families can then be targeted if they talk. For this reason, some Algerians living abroad who privately criticize the system will not do so openly, fearing for their families back home.

The Violence

In the aftermath of the military's 1992 seizure of power, radical Algerian Islamist groups took up arms and the country descended into civil war. While the many complexities of this conflict are beyond the scope of this analysis, it is important to recognize that the violence employed by all sides traumatized the population. Thousands disappeared without a trace. Torture became a routine measure in police interrogations. Assassinations of intellectuals, journalists, politicians, teachers, and unveiled women (then, in retaliation, veiled women) were widespread. In the midst of this civil strife, many members of Algeria's vocal Amazigh leadership were assassinated, such as Mahfoud Boucebci (a psychologist), Tahar Djaout (a writer-journalist), and Lounes Matoub (a singer and lyricist).

President Bouteflika was elected in 1999 and the "Civil Concord" was passed, offering amnesty to those militants who laid down their arms. The Islamic Salvation Army (AIS), the military wing of the FIS, cooperated with the amnesty, but the violence continued in areas where the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) continued its campaign of terror: one faction targeted civilians; the other targeted military personnel and their families.

As the violence dragged on, seemingly non-political civilians were massacred, on the road or at home, and entire villages were targeted, the people murdered and their bodies severely mutilated. Horror stories of babies thrown into cauldrons, fetuses removed from their mothers' wombs, young girls abducted, raped, and later killed, their throats slit from ear-to-ear, became commonplace. According to a number of reports, including those verified by Amnesty International, massacres often occurred only a few kilometers from army barracks, but no help came. At the very least, it can be said that the military did not come to the peoples' aid and did not do enough to bring them security. Local militias, backed by the government, were established to defend Algerian villages. These "Patriots," as they are called, also made the news in a few instances, accused of being themselves responsible for massacres. According to 1998 reports in Liberté and El Watan, a couple of town officials and numerous policemen and Patriots were under investigation for extortion, destruction of property, kidnapping, and summary executions. The mayors were accused by their own constituents of using the Patriots as death squads, targeting the mayors' personal enemies, as well as suspected Islamist militants and their sympathizers.

Independent newspapers that dared to place blame (either directly or indirectly) on the military for the persistent massacres plaguing Algeria have been closed down. La Nation, an independent newspaper headed by Salima Ghezzali, which dared criticize the pouvoir in such a fashion and allowed the publication of Islamist views, was shut down definitively in December 1997. Journalists were targeted for death or disappeared. Columnist Yassir Benmiloud, who dared point the finger at the generals in El Watan, was forced to go into exile in France. Entrepreneur Nesroulah Yous, who wrote a book entitled Who Killed In (the town of) Bentalha and accused the pouvoir of carrying out the massacre of some 400 villagers on September 22, 1997, also fled into exile. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Reporters sans frontières (RSF) have detailed the cases of Djamel Eddine Fahassi, Aziz Bouabdallah, and Salah Kitouni - three journalists who "disappeared" after criticizing the government (the cases of two journalists who were kidnapped and killed by armed Islamist groups were also investigated).3

The continued violence has raised some important questions. Was this truly still a political war, a fight between Islamists and the government they wished to overthrow? While previous killings by Islamists were sometimes followed by claims of responsibility and demands, this has not been true of recent massacres.

Why are the "Islamists" who terrorize the countryside not targeting vital installations of the state or profitable public companies? Indeed, their attacks seem to target unprofitable public companies, which "coincidentally" are scheduled for closure under the country's IMF restructuring program. Privatization increased vigorously after the start of the civil strife, and activities by the GIA were followed by "a phenomenon of privatization by the most exposed sectors" (e.g., transport). Instead of being laid off, which would have directed public ire toward the authorities, some 45,000 workers found themselves unemployed between 1992-95 due to the destruction of their workplaces by the GIA.4

Who finances the GIA? For what purpose? Surprisingly, these questions cannot be answered definitively. And why, if the government opposes the Islamists so vehemently, is the Family Code based on Islamic law, and why the recent enforcement of Islamist demands, resulting in arrests of young couples, whose crime has been to dare hold hands in public?

Conspiracy theories should always be taken with a grain of salt, but it is nevertheless important to recognize that growing numbers of Algerians believe that the GIA is, in some measure, linked to the pouvoir. Curiously, in a recent attack on the Kabyle village of Ait-Aissi, members of the village militia were mass-murdered, but when the gendarmerie came to investigate, they burned the militia's barracks, destroying all evidence.

In any case, it is certainly true that, whether by design or not, the continuation of violence has increased the power of the Algerian military by providing a pretext for continuing the state of emergency and suppression of political freedoms. This state of opaqueness and confusion is the most fertile environment for conducting illegal activities (black market, drug trafficking, etc.). Moreover, the struggle between Islamists and the government has polarized Algerian politics. Democratic opposition has been either normalized (i.e., the Rally for Culture and Democracy) or threatened and harassed (i.e., the FFS and Workers Party ).

Civil Society Fights Back

|

Souaidia's account, based on first-hand evidence, includes names, places, and dates that incriminate the pouvoir and their mafia-style network of corruption. He accuses the military of blaming armed Islamists for village massacres they themselves committed. He alleges that his colleagues in the army assassinated "in cold blood" suspected Islamists, tortured others to death, and even burned children alive.6 The Algerian government and press, controlled for the most part by the pouvoir, have tried desperately to discredit Souaidia and his book, accusing him of plagiarism and treason, to which Souaidia has responded that he is ready to return from exile in France if he can be assured of receiving a fair trial.

In April, the village committees of the Kabyle town of Beni Douala issued a declaration to the press which formally accused the local gendarmerie of drug and alcohol trafficking, money laundering, harassment and provocation at high schools, as well as ignoring reports of criminal activities and failing to protect the citizens. Prostitution, alcohol, and drugs have been drastically on the rise in Algeria, the information actually covered in the local news for over a year, and the situation evident to those who have gone back home for a visit, affirming that such activities are visible throughout the country, even in small villages where family values and family honor were once firmly instilled.

The civilian leaders of the Algerian government have taken some measures to respond to public concerns, but appear to have been checked by the pouvoir operating behind the scenes. Bouteflika's own campaign against corruption, which started in November 1999 and was formalized with the creation of the Algerian Association for the Struggle Against Corruption on December 31 of the same year, heralded an acknowledgement of the situation in the government, but focused exclusively on minor players (deputy governors, local council heads, etc.) who are considered dispensable. But the sources of the corruption, the big time mafia players, were never questioned, touched, or replaced. The one Algerian president who tried to expose the corruption of the mafia system in the past, Mohamed Boudiaf, was murdered on June 24, 1992, six months after taking office.

Conclusion

In retaliation for the Kabyle uprising, the Algerian Popular National Assembly7 (which itself has been accused of rampant cooruption) adopted on May 16 amendments to the Penal Code designed to further intimidate the population. Although journalists are the Penal Code's primary target, the new law is part of an overall policy intended to enhance the government's ability to crack down on popular dissent.8 This could potentially affect the Kabylia area most seriously due to the population's willingness to mobilize against the pouvoir in their fight for democracy. In the absence of a free press, what little restraint still exercised by the government in suppressing opposition is likely to diminish.

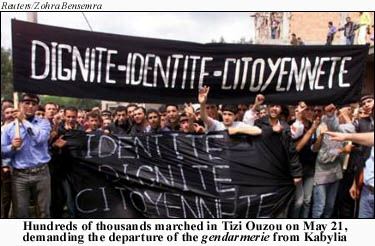

Nevertheless, the Kabyle uprising appears likely to continue. On May 21, Kabyle witnessed the largest protest march in Algerian history, with over half a million people taking to the streets of Tizi Ouzou to demand the withdrawal of the gendarmes, a more equitable sharing of oil revenues, and an end to the rule of the pouvoir.

Notes

1 The French term gendarmerie is used here to avoid confusion with the US police system. The gendarmerie are military police under the control of the Ministry of Defense.

2 For example, Gen. Betchine, who was ex-president Zeroual's main supporter among the pouvoir, was accused of financial irregularities during the end of the former president's reign. Betchine was a "reconciliator" (in favor of negotiating with the Islamists), as opposed to the "eradicator" generals who took over.

3 "Report: No serious investigation into 'disappearance' of five journalists; security forces implicated in three cases," RSF, 5 February 2001. Republished by the International Freedom of Expression Exchange. The report states: "There is no doubt whatsoever that the authorities are fully responsible for the "disappearance" of the latter three journalists. Everything points to the fact that the political leanings of two of them - Djamil Fahassi and Salah Kitouni - are the real reasons for them "disappearing." They were accused of sympathising with Islamist views."

See also "Alert Update: CPJ calls on Algeria to locate two 'disappeared' journalists," CPJ, 6 May 1999.

4 See "Islamists in the Economy of War," by Luis Martinez, Head of Research at the Center of Studies and International Research, Paris, 1999, translated by M. Sahnoun.

5 Habib Souaidia, La Sale Guerre (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2001).

6 Ibid., pp. 23-24.

7 Parliament does not have any real power. While it does vote on laws, the President can, between sessions (Spring and Winter breaks), issue an order which overturns the vote, effectively nullifying the formal power of the parliament. See Blanca Madani, Interview with Visiting Delegates, 25 February 2001.

8 Article 144 states that "anyone who insults a judge, an official, or a representative of the public order while he is exercising his job, with a word, a gesture, a threat, correspondence, a written article or a drawing . . . " will be incarcerated for "two months to two years" and be fined "10,000 DA to 500,000 DA"; Article 144 Section 1states that those who insult or defame the President of the Republic through "a written article or a drawing, a declaration, or all methods of diffusion," including "images, electronic methods," etc., will receive a jail sentence of "3 months to 12 months and a fine of 50,000 to 250,000 DA." In case of a repeat offense, the punishment "will be applied doubly." In addition, if the "crime" is committed through an article in a daily, weekly, or other publication, punishment will fall not just on the author, but also on those responsible for the publication and its editorial staff; Article 146 says that " . . . insults, outrage, and defamation through the means detailed in articles 144 and 144 Section 1 against Parliament or one of its houses, the courts . . . , the Popular National Army, or all other authority of the public order," will meet the same punishments described above, and in case of a second offense, the punishment will be doubled.