|

| Vol. 2 No. 11 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | December 2000 |

|

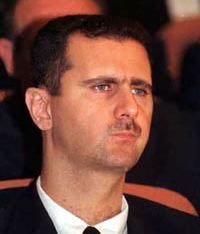

| Bashar Assad |

Suweida, a city of 160,000 located about 90 km south of Damascus and 40 km from the Jordanian border, and the surrounding governate have long been the site of intermittent conflicts over land ownership between the area's predominantly Druze inhabitants, who emigrated from Lebanon in the 18th century, and nomadic Sunni Bedouins. Although most Bedouins became settled along the outskirts of Suweida and in nearby villages over the years, a small number have remained nomadic, grazing cattle much as their ancestors have for thousands of years. Disputes between the two communities, usually arising when Bedouins try to graze their cattle (mostly sheep and goats) in orchards and vineyards owned by Druze residents, have been frequent, but had not evolved into large-scale violence in decades.

Last month's clashes originated in the village of Rahi on November 5 , when a group of Bedouins allegedly threw a dead donkey inside a Druze cemetery, and quickly evolved into a confrontation between Druze residents and local Bedouins armed with machine guns and grenade launchers. The fighting intensified and spread as the Druze launched reprisals against Sunni villages suspected of collaborating with the Bedouin, burning or damaging several homes and mosques. Bedouin gunmen soon blocked the main highway from Suweida to Damascus, randomly attacking Druze motorists.

Syrian Security forces intervened on the first day of the fighting and attempted to enforce a curfew, but were unable to contain the violence. Over the next three days, 20 people (14 Druze and 6 Sunnis) were killed and around 200 injured despite a massive deployment of troops and armored vehicles.

Meanwhile, as reports of the clashes began filtering into the Arab media, the Assad regime frantically attempted to cover up the scale of violent upheaval. On the third day of fighting, one official told the French AFP news agency that only a handful of deaths had occurred and that this conflict is "as old as the hills" and has no religious or political dimension. Not surprisingly (though in complete contradiction to the above spin), Syrian officials also attempted to portray the clashes as a Zionist plot, claiming to have seized Israeli-made Uzi submachine guns and other weapons in the area.1

Growing Dissent in the Druze Community

Outraged by the state's initial failure to put a stop to the attacks, Druze villagers stormed municipal and provincial government offices in Suweida, accusing local officials of sympathizing with the Bedouins. Many Druze have long believed that the Bedouin have secured grazing rights from the regime in return for operating as agents of Syrian intelligence.

As the fighting escalated, Druze throughout country staged public protests demanding that the Assad regime crack down on the Bedouins. Groups of Druze traveled to the capital and staged a demonstration outside the Ministry of the Interior and attempted to organize a protest in front of the parliament building. On the evening of November 8, around 200 Druze students staged a sit-in at the campus of Damascus University, demanding that a letter urging Assad to end the violence be delivered to the Syrian president.

The scale and intensity of Druze protests appear to have been fueled by another development. On November 3, Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt issued a call in parliament for the redeployment of Syrian troops in Lebanon. A member of the Lebanese branch of Syria's ruling Ba'ath party, MP Assem Qanso, responded by issuing a veiled threat of assassination and, days later, the Assad regime declared that Jumblatt was no longer welcome in Damascus in an official capacity. In reaction, thousands of Lebanese Druze demonstrated in Mukhtara to show solidarity with Jumblatt. Jumblatt's defiance of the Assad regime elicited a considerable amount of support from the Druze community in Suweida, where Jumblatt has been a frequent visitor. According to one report, pictures of Jumblatt "appeared in unprecedented numbers in Suweida, on walls, in shops, and on roadsides" during the clashes.2

Concerned that a show of weakness in the face of growing opposition could prove to be more disastrous than the clashes themselves, Syrian security forces reacted to this wave of dissent by forcibly dispersing demonstrations and arresting scores of Druze throughout the country.

The crackdown coincided with a highly publicized three-day visit by Assad to the city of Aleppo, carefully orchestrated to demonstrate continuing public support for the Syrian president. The state-run media portrayed the visit as a dramatic departure from official protocal, quoting "eyewitness accounts" of Assad mixing freely with the population as he strolled through the streets, "clinging to people in the most crowded parts of the city without bodyguards."3 Assad had originally planned to visit Suweida, but canceled the trip at the last moment due to concerns about his safety.4

Unrest in the governate of Suweida was finally brought under control on November 9. A few days later, Syrian army units tracked down the leader of the Bedouin militants, Saoud Said (some reports have identified him as Masoud Said). Two soldiers were killed in the operation.

On November 28, however, violence flared again with the killing of a Druze farmer, Wasim Fahd, by Bedouin gunmen. Two Druze were also injured in separate incidents. In reaction, thousands of Druze staged a protest in Suweida, demanding an end to the violence and the release of Druze detainees arrested earlier in the month. This time, however, the governor of Suweida, Muhammad Kikhia, personally addressed the demonstrators, promising that the killers of Fahd would be found. Unconfirmed reports indicated that most of the detainees were later released.

Notes

1 See Al-Diplomasi (London), December 2000.

2 Al-Quds Al-Arabi (London), 21 November 2000.

3 Al-Thawra (Damascus), 10 November 2000.

4 Al-Watan al-Arabi, 24 November 2000.