|

| Vol. 2 No. 6 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | 1 July 2000 |

| | Lt. Gen. Mustafa Tlass Syrian Minister of Defense, Deputy Prime Minister |

|

| Mustafa Tlass |

Mustafa Tlass was born in the village of al-Rastan near Homs in 1932, the son of a minor Sunni notable who made a living during Ottoman times by selling ammunition to the Turkish garrisons.1 By the time the Ottomans left Syria in 1918, Abdul-Kader Tlass had secured a small fortune for his children's education. The young Tlass studied at his home village and moved down to Homs to enroll in the Baath Party in 1947. He was attracted to its secular, pan-Arabist doctrine and became a preacher of its cause at the age of 15. In 1952, Tlass enrolled at the Homs Military Academy where he met an air force pilot who was to become his life-long companion, Hafez Assad. In 1954, Tlass left the academy and became an officer in the Syrian army. When the United Arab Republic was created between Syria and Egypt in 1958, Gamal Abdul Nasser stationed many Syrian Baathist officers in Cairo to keep them from political mischief in Damascus. Among those to take up a three-year residence in Egypt were Hafez Assad and Mustafa Tlass. When the United Arab Republic was dissolved on September 28, 1961, the Egyptian president imprisoned several Syrian officers put in jail, including Assad. Tlass escaped in time and returned to Syria by sea, escorting back with him Assad's wife and baby daughter.2

During the early 1960s, Assad and Tlass became close friends. Both were disillusioned by the policies of President Nazem al-Kudsi and criticized his anti-Nasser policies. While Assad began to participate in anti-regime activities, Tlass stood by and watched, preferring a marginal role in political affairs. On March 8, 1963, the Baath Party took power in Syria, and Hafez Assad was part of the Revolutionary Council. Mustafa Tlass played no role in the coup, but as a reward for his friendship to the now powerful Assad, he was appointed to the Baath Military Committee and given command of a small armed division. Assad, on the other hand, became Chief of the Syrian Air Force.

The first real challenge facing the new decision-makers was the opposition based in the conservative city of Hama. Headed by prominent Muslim figures the movement gained wide appeal and began to criticize the secular, socialist doctrine of the Baath Party. In April 1954, something of a religious war broke out, headed by the Muslim Brotherhood, who were to remain the Baath Party's prime enemy in future years. They took control of the city and began to persecute members of the Party. Many were killed, while others were beaten in public. The insurgents took hold of the central mosque and declared a revolution against the regime. President Amin al-Hafez called for a meeting of the Regional Command, of which Assad was a member, to decide how to deal with the matter. With an anonymous vote, they gave orders that the mosque was to be shelled. The army struck with force, and seventy Muslim Brotherhood chiefs were killed.3 In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, Assad instructed Tlass with the task of bringing the insurgents to justice. He was appointed head of a military tribunal, a position that enabled him to prove his loyalty to the regime. As a reward for his services, he was appointed to the Baath Regional Command in August 1965.

By the mid-1960s, Tlass had become a key officer in Syria. Although President Amin al-Hafez was a Sunni, he was on opposite ends with Tlass, who accused him of being sectarian in his policies. In early 1965, Tlass was stationed in Homs but lost his post a few months later for having dismissed several officers who were loyal to the President. His alienation against the regime increased. Among those to face similar persecution were his two friends, the Alawite officers Hafez Assad and Salah Jadid. As a result, the Alawite coalition launched a military coup d'etat on February 23, 1966. President Amin al-Hafez and the Party's founder Michel Aflaq were toppled and chased out of Syria. The new leadership included Hafez Assad as Minister of Defense and Salah Jadid as Assistant Secretary General of the Baath Party. Although Tlass received no official post, his influence increased in Syrian circles, for he was known Assad's protégé.

Following the War of 1967, the Baath Party suffered a split in its ranks with Hafez Assad on one front and Salah Jadid on the other. Each saw the other as blameworthy of defeat, and as the days went by, the hostility became public. To increase his political clout, Assad dismissed the Jadid loyalist Ahmad Suwaydani from the post of Chief of Staff in February 1968 and appointed Mustafa Tlass instead.4 To add to his friend's influence, he made him Deputy Minister of Defense. His post was largely ceremonial, however, and it did not last long. On November 13 at a meeting of the Baath National Command, orchestrated by Jadid, resolutions were passed to dismiss Assad and Tlass from the army and strip them of their government posts. The National Command was composed of a majority of Jadid loyalists. No sooner had the resolutions been passed than Assad's forces took to the streets, arrested President Noor al-Din al-Atassi, Salah Jadid, and anyone who was in the slightest connection of being their supporter. Both Jadid and Atassi were put in jail, where they died respectively in 1992 and 1993. On November 16, 1970 Assad declared that this was his "Correctional Movement" and that he had assumed leadership of the nation.

Assad captured the state with relative ease and began to appoint his closest supporters to key positions. Mustafa Tlass was promoted to the rank of imad, a position created specifically to distinguish him from other officers who held the title of liwa. Tlass was also appointed Minister of Defense in 1972, Deputy Commander in Chief of the Syrian Army and Deputy Prime Minister for military affairs. In addition to showing gratitude for a faithful friendship, the appointment of Tlass was also designed to appease the nation's Sunni majority and avoid accusations that the new regime was dominated by the Alawites. Tlass's first task in the Syrian regime was to negotiate between King Hussein of Jordan and the PLO leadership, who in September 1970 waged a full-scale war against one another in which Syria sided with the Palestinians. Meeting Hussein in Amman, Tlass was able to secure for the Palestinian guerrillas sanctuaries overlooking the Jordan Valley, but obsessed by animosity towards the King, they refused the offer and moved on to Lebanon, a development that would plant the seeds for the Lebanese Civil War in 1975.5

During the October War of 1973, Tlass never left Assad's side--the Syrian President would later describe him as a reliable friend who could be relied upon in times of need. During the initial planning for the war, Tlass had served as Assad's special envoy, making shuttle visits between Damascus and Cairo to negotiate the coordinated attack. In the post-war era, Tlass became Assad's envoy to Moscow, making constant visits with the aim of purchasing more arms and expanding the Syrian army. Tlass established good relations with the Russians, especially Premier Leonid Brezhnev, who became a personal friend. When Brezhnev died in November 1982, Tlass attended his funeral with President Assad, and began to gain influence in Russian circles. Through his collaboration with the USSR, Tlass was able to expand the Syrian army from 225,000 in 1982 to 400,000 in 1986. The armored divisions were expanded from 3,200 to 4,400 tanks, and 440 to 650 aircraft during this period.

When Assad suffered a heart attack in 1984, he again relied on Mustafa Tlass for support. His brother Rifaat, director of the Defense Corps, began plotting for a coup d'etat and deploying his troops in Damascus to capture the state. From his sickbed, Assad appointed a six-man team to deputize for him in the crisis. All of them were Sunnis, and Mustafa Tlass was first on the list. A crisis for power ensued, and Syria seemed on the verge of a bloody coup d'etat. The President ended the crisis personally, however, and sent Rifaat into exile. The task of denouncing the President's brother was given to Mustafa Tlass, who declared in an interview with the German newspaper Des Speigel that "Rifaat Assad is permanently persona non grata." It was the first public condemnation of Rifaat and marked the beginning of his permanent estrangement from the regime.

Following the Rifaat ordeal, political life in Syria cooled down. All decision-making was centralized in the hands of the President and no one, not even Tlass, was welcome to share in the duties. Tlass lived on in pomp and glory, retaining his position of Defense Minister and turning into a social rather than political figure. Being a Sunni, he befriended the Damascene Sunni elite and began to establish himself as one of them. His marriage to Lamia al-Jabiri, a lady who belonged to the Aleppine aristocracy, secured his position among the traditional elite and opened doors for social advancement that otherwise would have remained closed. His two male sons also pursued prestigious marriages. Firas, his eldest, studied in Paris and became one of Syria's most prominent food merchants. He married Rania al-Jabiri, a young lady from Aleppo who was also a part of the Aleppine upper class. His other son, Manaf, enrolled at the Military Academy and pursued a military career. He also became a close friend of Basil Assad, the President's eldest son and heir apparent, who was killed in a car crash in 1994. Following the accident, Basil's brother Bashar took up the duties of his brother and inherited, among other things, Manaf Tlass's friendship. When Hafez Assad died in 2000, Manaf became Bashar's right-hand-man, and a potential candidate for leadership in future years. Like his father and brother, Manaf also married into an aristocratic Damascene family. His wife, Tala Kheir, was the daughter of a Damascene intellectual and granddaughter of the nationalist merchant, Adib Kheir. His eldest daughter Nahed was married to the Paris-based Syrian multi-millionaire Akram al-Oujje and his youngest daughter Sarya was married to a Lebanese young man from Baalbak.

In short, Tlass was the only member of the Baath regime who penetrated the traditional social establishment of Syria. He soon established himself as a patron of the arts and a man of books and knowledge. He opened a publishing house in Damascus and was the first person to make an attempt at revealing pre-Baath Syria in an objective manner. He has written several books that cover the widest variety of subjects. Among his works are a eulogy of Nizar Kabbani, a history of the Arab Revolt of 1916, several ant-Israeli (some say antisemitic) works, and of course, books dealing with Hafez Assad. By far, his most important work is a two-volume memoir entitled Mirror of My Life. Its importance comes from the fact that its author is the only Syrian politician since 1963 who has laid down his memoirs for history.

|

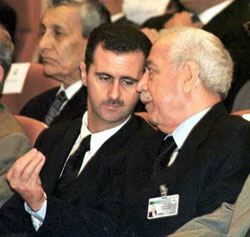

| Bashar Assad confers with Tlass at the ninth Baath party conference on June 17 (AP/Hussein Malla) |

In 2000, the ailing Syrian president began a series of corruption trials to improve the reputation of his regime and give credibility to his son. Several of the nation's most prominent figures were investigated on corruption and embezzlement charges, such as former prime minister Mahmoud al-Zu'bi (who committed suicide afterwards) and former chief-of-staff Hikmat Shihabi (who fled into exile). Not surprisingly, Tlass was immune to the measures taking place around him. During a celebration of the creation of the Syrian and Lebanese armies on August 1, 1999 Tlass, having been annoyed by PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, declared before national television that "Abu Ammar is a son of sixty-thousand whores." The statement caused uproar in Palestinian circles and brought about heavy criticism on Assad. Yet, despite all these pressures, Assad did not punish or dismiss him. The outspoken Tlass has made other inappropriate public statements in the past that have greatly embarrassed the regime, most notably his remark in January 1991 that he felt "overwhelming joy" when Iraqi SCUD missiles landed in Israel.6 American officials were outraged, but again Tlass escaped rebuke from Assad.

When the Miru government came into effect in March 2000, Tlass was again chosen for the Ministry of Defense, marking his twenty-eighth year in the same job. Hafez Assad's death on June 10 left Tlass and the entire Syrian team in chaos. For a few hours following the death, it was rumored that Tlass had assumed the presidency, but it was eventually established that Bashar Assad had secured it with the blessing of Tlass. In June, the ninth congress of the Baath Party Regional Command voted Tlass as part of the six-man team responsible for aiding Bashar in his duties as Secretary-General of the Baath Party.

Being the "old man" of the regime and the President's faithful companion, his influence has quadrupled in the post-Assad era. He has not parted from the young leader's side, either in private meetings or before the cameras. He remains, however, without an autonomous power base of his own. Being a Sunni at the top of a predominantly Alawite establishment, he cannot exercise any influence independently of his relationship with Bashar.

1 Hanna Batatu, Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Rural Notables, and Their Politics (Princeton University Press, 1999), p.152.

2 Patrick Seale, Asad: The Struggle for the Middle East (University of California Press, 1988), p. 68.

3 Ibid., p. 93.

4 Nicolas Van Dam The Struggle For Power in Syria, p.165

5 Seale, p. 282.

6 Al-Thawra, 21 January 1991.