|

| Vol. 3 No. 4 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | April 2001 |

|

Background

Relations between the Assad regime and Yasser Arafat have always exhibited tensions stemming from a fundamental conflict of interest - both have striven to assert political control over Palestinian communities stretching from the Israeli-occupied territories to Lebanon and Syria.

These inherent tensions in the relationship erupted in 1976, when Syrian forces entered Lebanon and clashed with the PLO. Although the 1978 Camp David Accords temporarily led Assad and Arafat to reconcile, their rivalry again erupted when Arafat began embracing the idea of an American-sponsored resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the early 1980s. In 1981, Arafat accepted a peace plan proposed by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia and a cease-fire agreement with Israel in south Lebanon, outraging the Syrians, who consequentially did little to assist Palestinian guerrillas in Lebanon against invading Israeli forces in 1982.

Assad began openly preparing to destroy Arafat after the Palestinian leader declared his conditional acceptance of the September 1982 Reagan peace plan and Syrian intelligence discovered that Arafat was harboring a number of Syrian Islamists opposed to the Assad regime. In the summer of 1983, after Arafat's defeated guerrillas relocated to the northern Lebanese port of Tripoli, Syria promoted a rebellion against Arafat within the Fatah movement by Col. Abu Musa, whose forces managed to drive Arafat entirely out of Lebanon.

In 1984, Assad's estranged brother, Vice-President Rifaat Assad, met openly with Arafat in Geneva shortly after his forced exile from the country. Meanwhile, throughout the 1980's, Syria continued its brutal campaign of massacres and assassinations against pro-Arafat forces in Lebanon through the so-called National Salvation Front, an umbrella organization consisting of Saiqa (a Palestinian force operating in conjunction with the Syrian army) and extremist Palestinian factions headed by Abu Musa, Ahmad Jibril, George Habash, and Nayif Hawatmeh. Thousands of Palestinians were transferred to Syria and imprisoned in detention centers in an around Damascus. In 1989-1990, Arafat openly backed Lebanese Interim Prime Minister Michel Aoun in his "war of liberation" against Syrian forces in Lebanon.

The conflict between Arafat and the Syrian regime was further fueled by Arafat's decision to secretly negotiate the 1993 Oslo Accords with Israel, a move which Assad considered to be an underhanded violation of the comprehensive peace framework established at the 1991 Madrid conference. Syrian sponsorship of Arafat's leftist and Islamist opponents in the West Bank and Gaza proved to be a powerful tool in discouraging Palestinian concessions to Israel.

In 1998, Palestinian-Syrian relations reached their lowest point in years. In July, Rifaat Assad's son, Sumer, traveled to Gaza and was warmly received by Arafat. During his visit, Sumer publicly praised the "friendship" between Arafat and his father. Syria quickly retaliated. On August 2, Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass publicly condemned Arafat in an unusually graphic speech (even for Tlass). "Son of 60,000 whores . . . you should have told the White House that Jerusalem is the capital of the future Palestinian state. Instead you stayed as quiet as a mouse and did not dare say even a single word in favor of Palestine or Jerusalem," declared Tlass. "Look at him when he's on the stage," he continued, "he moves from concession to concession, like a stripper, except that [the stripper] becomes more beautiful with every layer she removes, while Arafat becomes uglier." This sparked anti-Syrian demonstrations in Gaza, the West Bank, and the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp in Lebanon.

The death of Assad in June 2000 removed an important impediment to the improvement of relations between the two sides. As Syrian political commentator Ghassan al-Imam noted in 1998, Assad "is a meticulous, organized, cautious and serene person . . . he is serious and keeps his word," whereas Arafat "is less cautious and more prone to political U-turns." These differences, he said, made "a healthy relationship impossible to establish."

Steps toward Reconciliation

That Assad's death would herald a new phase in Palestinian-Syrian relations was evident from the very beginning - Arafat attended Assad's funeral at the invitation of the Syrian regime. When Rifaat Assad publicly challenged the legitimacy of Bashar Assad's succession as president of Syria, Arafat distanced himself from Bashar's exiled uncle. Rifaat desperately sought a meeting with Arafat through two friends of Sumer (Dr. Khalid Salam, an economic adviser close to Arafat, and Hisham Makki, a PA media official), but was rebuffed.1

After the eruption of the Al-Aqsa Intifada last year, which appeared to destroy the Oslo peace process that had raised the ire of Assad's father, Palestinian and Syrian officials started discussing a reconciliation through intermediaries. Farouk Qaddoumi, the chairman of the PLO's political department who had initially distanced himself from the Oslo Accords, made several trips to Damascus on behalf of Arafat. Earlier this year, Assad and Arafat began speaking regularly on the telephone.

In January 2001, Syria began allowing imports of agricultural products from the Palestinian self-rule areas for the first time.2 Previously, Syria had barred products bearing a Palestinian certificate of origin, claiming that such items were produced within Israeli-occupied territories. However, the Syrians turned down Arafat's repeated requests to meet Assad in Damascus. "Syria's doors are wide open," Assad told Al-Sharq Al-Awsat in February, "but meetings must have an agreed agenda." He added that Syria demanded the "full restoration" of Palestinian rights and "any coordination with the Palestinian side must be in this direction."3

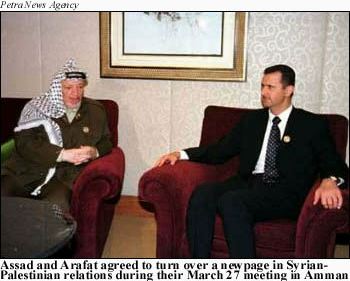

During the weeks preceding the Arab summit in March, the talks intensified and plans for a meeting between Assad and Arafat were revealed to the press after Arafat agreed to Syrian demands (see below). Upon his arrival at the summit, Assad publicly urged the Palestinians to forget the past: "We say: Let bygones be bygones. We don't live in the past, but learn lessons from it."4

Assad and Arafat met for forty-five minutes in a secluded room at Jordan's Palace of Conferences, accompanied by Syrian Vice-President Abdul Halim Khaddam, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouq al-Shar'a and two Palestinian officials, Nabil Shaath and Saib Urayqat. The two sides discussed a reconciliation agreement, the details of which had been under negotiation for several weeks. The plan called for Arafat to observe five basic principles demanded by the Syrians: 1) UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 shall be adhered to in future talks with the Israelis; 2) The establishment of a Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital shall not be compromised; 3) The repatriation of Palestinian refugees in accordance with UN General Assembly Resolution 194 shall not be compromised; 4) The Al-Aqsa Intifada shall be continued and escalated; and 5) The Palestinian, Syrian and Lebanese tracks of the peace process shall be unified.5

Although Palestinian sources later denied that Arafat signed the agreement,6 subsequent developments suggest that some parts of it were explicitly agreed upon. Moreover, in the weeks following the meeting Syrian officials and the state-run media have begun referring to Arafat as President of the Palestinian Authority (rather than PLO chairman) for the first time since the 1993 Oslo Agreements. Syrian customs officials now recognize passports issued by the PA. In addition, the Syrians have said they will permit the PA to open an embassy in Damascus. According to the Saudi daily Al-Madina, the agreement also requires Syria to release properties and other assets of the Fatah movement that were frozen in 1983, estimated to be worth millions of dollars, and open talks regarding the thousands of Palestinian detainees held in Syrian prisons.7

Full implementation of the agreement will probably follow Arafat's visit to Damascus later this month. In early April, Qaddoumi traveled to Damascus to make arrangements for the trip. According to Al-Hayat, Arafat is to be treated for the first time as a visiting head of state. Assad will meet him at the airport and the Palestinian national anthem will be played during an official reception.8

The Assad regime's new posture towards the PA has been mirrored by its client regime in neighboring Lebanon. During the Amman summit, the Syrians permitted Lebanese President Emile Lahoud to meet with Arafat - the first time since 1982 that a Lebanese head of state has met with the Palestinian leader. Last month, a member of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri's parliamentary bloc, MP Nasir Qandil, met with the secretary-general of Arafat's Fatah movement in Lebanon, Sultan Abul-Ainein, at the Rashidieh Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. However, while the meeting was publicized as a Lebanese-PA diplomatic breakthrough, it is noteworthy that Qandil is a close confidant of Assad - the Syrians clearly want to keep closed tabs on this relationship.

One stumbling block to Palestinian-Syrian reconciliation will no doubt be the coalition of radical Palestinian groups hosted by Damascus. Ahmad Jibril, the secretary-general of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), recently stated that his group will cooperate with Arafat only if the PLO charter is re-amended to include clauses calling for Israel's destruction that were taken out in December 1998 under American and Israeli pressure.9

Notes

1 Al-Arab al-Yawm (Amman), 7 August 2000.

2 Al-Ayyam (Ramallah), 25 January 2001.

3 Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, 9 February 2001.

4 UPI, 27 March 2001.

5 Al-Hayat (London), 25 March 2001, SANA (Damascus), 26 March 2001.

6 Al-Majd (Amman), 2 April 2001.

7 Al-Madina (Saudi Arabia), 4 April 2001.

8 Al-Hayat (London), 19 April 2001.

9 AFP, 15 April 2001.