|

| Vol. 3 No. 4 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | April 2001 |

|

Lebanese Muslims and the Syrian Occupation

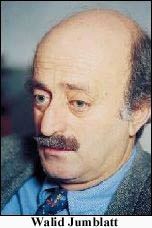

In an interview last month with the French-language Lebanese daily newspaper L'Orient Le Jour, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt complained that Lebanese Muslim leaders do not dare say publicly what they think about occupying Syrian forces. "We face a major obstacle - there is no Muslim leader who raises the issue of the Syrian presence."1

Jumblatt did not explain why this is so, but the answer can be gleaned from lists of Lebanese detainees released from Syrian prisons over the last few years. Of the 121 Lebanese detainees released from Syrian prisons in March 1998, all but thirteen were Muslims. All but a handful of the 46 detainees who arrived home form Syria in December 2000 were Muslims. While the sectarian distribution of previously-released detainees is probably not entirely representative of those who remain behind (some have complained that Christian detainees are being held back), it is nevertheless clear that the overwhelming majority of Lebanese abducted by Syrian forces have been Sunni and Shi'ite Muslims.

This disproportionate sectarian distribution is indicative of a broader trend: the Syrian occupation has been far more intrusive for Muslim Lebanese. In part, Christian Lebanese are less victimized because they can more easily draw international attention to Syrian human rights abuses - they are more prosperous, more likely to be fluent in English or French, and more likely to have relatives living in the United States and other Western countries. It is also true, of course, that the West has been much more prone to react when the victims of Syrian atrocities are Christians.

A second factor contributing to this evident (but very counterintuitive) sectarian imbalance in Syrian coercion stems from the manner in which Syria justifies its occupation at home and in the larger Arab world. According to this legitimizing narrative, Lebanese opponents of Syria are reactionary Christian extremists aligned with Israel. Whereas expressions of anti-Syrian sentiments among Christians in Lebanon can easily be explained away within the context of this narrative (and even seem to reinforce its validity), expressions of anti-Syrian sentiment within the Muslim community contradict this portrait and are therefore considered to be much more threatening.

The Syrian government, an Alawite-dominated regime which rules over a majority Sunni population at home, has long been particularly intolerant of Lebanese Sunnis who deviate from Syrian "red lines." Muhammad Shuqair, an advisor to former President Amine Gemayel who took an active part in negotiating the 1983 peace agreement with Israel (a definite no-no in Syria's eyes) was assassinated in August 1987. Muslim MP Nazim Qadri was assassinated in 1989 just hours before he was scheduled to have lunch with Michel Aoun (another definite no-no).

The Syrians have been particularly paranoid of discontent among Sunni religious leaders, fearing that they might incite Sunni Islamist groups in Syria against secular Alawite rule. This was particularly evident when the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood revolted against the Assad regime in the 1980's, during which a long line of distinguished Lebanese Sunni clerics were assassinated after raising objections to the Syrian presence. Sheikh Ahmad Assaf was killed in April 1982. Sheikh Subhi al-Salih, a respected Sunni theologian who wrote many books on Islam and participated extensively in interreligious dialogues, perished in October 1986 after making several statements criticizing Syria's role in fanning sectarianism. In May 1989, the Grand Mufti of the Lebanese Sunni community, Hassan Khalid, was assassinated just days after meeting with officials from Aoun's administration.

In recent years, Syrian intelligence in Lebanon has devoted considerable resources to coopting and intimidating Sunni religious leaders. These efforts are most evident in eastern and northern Lebanon, where the concentration of Syrian military and intelligence forces is strongest. The most blatant case is a group of clerics whose activities are orchestrated by the head of Syrian intelligence in Akkar, Muhammad Muflih. The so-called "Akkar Ulama" regularly publish inflammatory condemnations of those who criticize the Syrian occupation.

The Veil of Silence Lifts

After the death of Syrian President Hafez Assad and the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon last year, overt expressions of Muslim opposition to the Syrian occupation started becoming decidedly more frequent. Initially this was evident mainly among university students, due to their youth and exposure to critical discourse, and farmers, due to their direct stake in ending the unregulated entry of Syrian agricultural products into the country. In recent months, this trend has slowly spread to political elites.

The Druze

Druze leader Walid Jumblatt was the first prominent Muslim politician to take the plunge, though he did so gradually and primarily for self-serving aims. Having been sidelined in 1998 by newly-"elected" President Emile Lahoud, Jumblatt became an outspoken critic of the "militarization" of the Lebanese regime. Last year, his attacks on the security forces began evolving into criticism of Syria, carefully calibrated to win Christian support in the 2000 parliamentary elections while observing Syrian "red lines." The majority of Druze political elites followed suit.

|

Last month, it began to boil over. On March 16, during a ceremony in Mukhtara to commemorate the 24th anniversary of the assassination of his father Kamal Jumblatt (widely believed to have been ordered by Syrian President Hafez Assad), the Druze chieftain reiterated his objections to the Syrian presence.3 In an interview with L'Orient-Le Jour published the same day, Jumblatt ridiculed Lebanese and Syrian officials who claim that the two countries have a common destiny. "What do they mean by common destiny? Do they mean union? If so, union is not brought about in this way. It must be reached through plebiscites in both countries. We have a democratic system, whereas they have a one-party system," said Jumblatt, adding that he supported Arab unity only "on the model of the European Union, where liberties and democracy are respected."4

On March 18, an unidentified Syrian official quoted by the London-based Al-Sharq Al-Awsat declared that Jumblatt was "unworthy of any concern" and then (without any hint of irony) proceeded to launch an unprecedented polemical diatribe against the Druze leader. "Syria knows that Jumblatt separated himself from the nationalist drive by deciding not to combat the 1982 Israeli invasion in the Shouf mountains," said the official in reference to Jumblatt's brief flirtation with Israel. "He also distanced himself from the patriotic achievements of the Druze community in Lebanon and Syria." The official also accused Jumblatt of supporting the election of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and opposing the "non-sectarian and nationalist spirit" of President Emile Lahoud.5

The Sunnis

Meanwhile, overt opposition to the Syrian occupation within the Sunni Muslim community was becoming very evident. On March 20, Aliah al-Solh, a daughter of the late prime minister Riad al-Solh, wrote a scathing editorial in Al-Nahar, arguing that Assad shares his father's ambition to control Lebanon. The differences, she wrote, are that the younger Assad is more interested in "the investments of Lebanon's tycoons" than the land of Lebanon itself and seeks to avoid foreign criticism by shifting the locus of Syrian control from the "army to the [security] agencies."6

A number of prominent Sunnis are members of the National Gathering for Salvation and Change, a new multi-confessional group which held its first conference on March 31 and April 1, including MP Mustapha Saad, the head of the Nasserite movement in Sidon, Ghada al-Yafi, the daughter of former Prime Minister Abdullah al-Yafi, and Assem Salam, a former head of the Lebanese Engineers' syndicate. The group released a statement at the end of the conference condemning what it termed "a faulty and unbalanced relationship, characterized by subordination and adulation on the Lebanese side." 7

Earlier this month former Prime Minister Selim al-Hoss announced the formation of the National Action Front (NAF), which released a statement calling for a the establishment of an "equitable relationship between the states of Lebanon and Syria to stop one from interfering in the domestic affairs of the other." The defection of Hoss is significant, as he headed the Syrian puppet regime in West Beirut that facilitated Syria's takeover in 1990.8

Naturally, the above-mentioned "Akkar Ulama" organized by Syria have been going ballistic. Last month, one of the Akkar clerics even went so far as to accuse Sunni Grand Mufti Muhammad Rashid Qabbani of "conspiring" with Maronite Christian Patriarch Boutros Nasrallah Sfeir against Syria, an unprecedented act of slander which drew sharp rebukes throughout the Sunni community. Even Akkar MP Wajih Baarini, who is very close to the Syrians, said he found it offensive that such "a small sheikh" should accuse the grand mufti.9

The Shi'ites

|

However, this has begun to change. Last November, in an apparent attempt to win public favor and position himself as the principal intermediary between Damascus and the Christian political establishment, Berri announced that Syrian forces would undertake a redeployment to the Beqaa Valley "in the near future." Berri's bizarre statement, which he made after meeting with Patriarch Sfeir, was immediately disavowed by Syrian officials.10

In February, Habib Sadek, the president of the Southern Lebanon Cultural Council and a former MP, signed a petition by the Democratic Forum which called on the government to "rectify Lebanese-Syrian relations based on a relationship of equals which will reinforce national sovereignty and independent decision-making."11

Earlier this month, the acting chief of the Higher Shi'ite Council, Abdel-Amir Qabalan, called for the redeployment of Syrian forces to the eastern Beqaa Valley as stipulated in the 1989 Ta'if Accord.

The most vocal dissenter among Shi'ite political leaders is Kamil al-Asa'ad, a former speaker of parliament. On April 9, Asa'ad and a delegation representing his Socialist Democratic Party (SDP) met with the Maronite Christian patriarch and thanked him for adopting a stand "on behalf of all Lebanese." He told reporters afterwards that "both Muslims and Christians believe in the country's independence, freedom, and democratic system."12 Another prominent Shi'ite opposed to the Syrian occupation, former MP Rafiq Shahine, is also a member of the SDP.

Syria Strikes Back

Needless to say, this unprecedented rise in overt expressions of Muslim opposition to Syrian hegemony set off alarms in the offices of Maj. Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, the chief of Syrian intelligence in Lebanon. For months, Syrian and Lebanese officials had been repeatedly declaring that anti-Syrian sentiments were confined to a small minority of extremist Christian agitators. Although the emptiness of this claim had long been evident to anyone venturing near university campuses, where Michel Aoun's Free National Current (FNC) has garnered considerable support from Muslim students, it was still possible to sell this myth to the outside world so long as mainstream Muslim political figures kept quiet. As this veil of silence began to erode last month, Kanaan initiated a series of countermeasures.

The Shouf Deployment

On March 19, according to a Reuters news wire report, Syrian military forces advanced into the mountainous Shouf region and took up positions around Mukhtara, Jumblatt's ancestral home. Although Syrian troop movements in the Shouf had been reported by the Lebanese press as early as March 8,13 rumors of the deployment seemed to gain credibility from the Reuters report, which was splashed across the headlines of most daily newspapers in the country.

Jumblatt told reporters that he would "rather not discuss" the matter, quickly adding that "if strategic purposes call for Syrian troops to deploy on the mountain, there is no problem."14 But news of the deployment disrupted what was to have been a parliamentary session devoted to budgetary matters. "What does the Syrian deployment in the Shouf today, with heavy weapons, mean?" declared MP Albert Moukheiber. "I demand to know what the government's position is on these actions which take place on Lebanese soil."15 This sparked a series of tense exchanges between pro-Syrian deputies and a handful of other Christian MPs.

The Hezbollah Card

The student protests organized by the FNC on March 14 and the massive display of support for Patriarch Sfeir upon his return from a visit to the North America on March 27 both proved embarrassing to the Syrians. The estimated 100,000 people who turned out to greet Sfeir, many of whom overtly shouted anti-Syrian slogans, constituted the largest popular demonstration in Lebanon in recent years. Not surprisingly, Damascus wanted to organize an even larger demonstration of support for its military presence in Lebanon. The only force in Lebanon capable of doing this was Hezbollah, and the Shi'ite holiday of Ashoura was an ideal occasion.

The relationship between Hezbollah, a militant Islamic fundamentalist movement, and the avowedly secular Syrian regime has long been, as one Beirut commentator recently observed, a "loveless marriage that endures because their common interests demand it."16 While Hezbollah officials generally express support for Damascus, they have avoided the kind of exaggerated paeans of support for the Syrian occupation that are routinely made by President Emile Lahoud, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri and other close allies of Syria.

The reason for this is quite straightforward: Whereas most of Syria's political clients in Lebanon have little indigenous support (and no political future once Syrian forces depart from the country), Hezbollah has cultivated an impressive level of popular support, both among its own Shi'ite constituents and the population at large. This support stems from several factors. First, Hezbollah's armed struggle against Israel garnered widespread support in Lebanon. This campaign capitalized not only on the antipathy toward Israel felt by many Lebanese, but also on the humiliation felt by all Lebanese over their country's loss of independence to outsiders.

Second, unlike most other ethno-sectarian factions in Lebanon, Hezbollah did not fight against armed groups affiliated with other religious communities during the 1975-1990 civil war. While its internecine conflict with the rival Shi'ite Amal movement during the closing years of the war resulted in many causalities, most analysts agree that the head of the Amal movement, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, bore responsibility for the violence. Consequentially, writes Al-Nahar journalist Nicolas Naseef, Hezbollah is perceived as "the only Lebanese armed group that does not have Lebanese blood on its hands."17

Third, like many other Islamist movements in the region, Hezbollah has a reputation for asceticism that contrasts sharply with the pervasive corruption that infects Lebanese politics at all levels. Even the movement's most virulent detractors concede that the notion of a corrupt Hezbollah official is virtually a contradiction in terms.

Fourth, Hezbollah has always distanced itself from the mainstream political elite in Lebanon that embraced the entry of Syrian forces into the country. The group opposed the 1989 Ta'if Accord which virtually ceded control of the country to Damascus. At the grassroots level, many Hezbollah activists worked closely with members of the Free National Current in opposing corruption and political patronage. For instance, when the Lebanese doctors' association held elections last month for a new chairman, Hezbollah and the FNC both backed the losing candidate, Dr. Saad Bizri, over Dr. Mahmoud Shuqair, who enjoyed the firm backing of political heavyweights such as Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri and Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri.

It was therefore quite a publicity coup for Damascus when Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah spoke before 300,000 followers on April 4 and gave by far his most ringing endorsement ever of the Syrian occupation. The presence of Syrian forces in Lebanon is "a regional and internal necessity for Lebanon" and a "national obligation for Syria," declared Nasrallah. "Should the Syrian leadership take its army out of Lebanon, we as Lebanese will stand up and tell them they are wrong and are doing something which is not in Lebanon's interest," he added.

Threats, Arson and an Assassination Attempt

Emboldened, perhaps, by this display of sectarianism, Jumblatt's PSP joined three secular, multisectarian groups (the FNC, the Communist party, and the leftist Democratic Forum of former MP Najah Wakim) and the right-wing Christian Lebanese Forces movement in calling for a mass rally in downtown Beirut on April 11 to commemorate the 26th anniversary of the Lebanese civil war (held two days early in order not to conflict with Good Friday). Organizers of the rally said that the event would illustrate that Muslims and Christians had fully reconciled - contrary to Syrian propaganda claiming that the withdrawal of Syrian forces would reignite sectarian unrest.

Not surprisingly, the Lebanese interior ministry quickly issued a ban on all public protests or marches marking the beginning of the war. In keeping with the government's claims that only extremist Christians are opposed to the occupation, the statement said that the ban was designed to prevent "attempts to instigate sensitivities and civil strife."

|

High-ranking members of the FNC were soon bombarded by threats from anonymous cellular telephone callers. All of the recipients were told exactly the same thing: "If we see you on April 11, blame only yourself for what happens."18 Najah Wakim, the head of the Democratic Forum, also received repeated death threats.

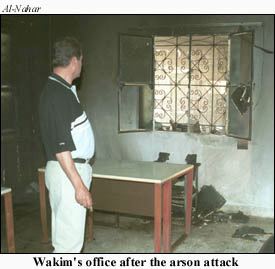

On the morning of April 9, Wakim arrived at work to find that his office in Mosseitbeh had been badly damaged by a fire. A broken window in the second story office and an empty bottle that smelled of gasoline indicated arson. "I called the Ramlet al-Bayda police station and the Internal Security Forces Headquarters at 8.45 AM today. I found no one at the ISF, and no policemen have been dispatched until now," Wakim said in an interview at 2:00 PM that day.19

Government investigators eventually arrived, and, according to Wakim, quickly determined that the fire was caused by an electrical short circuit (even though there was no electrical wiring where the fire broke out). More help soon arrived from the Central Criminal Investigations Department, which proceeded to tap Wakim's phone, ostensibly to investigate the threatening phone calls.

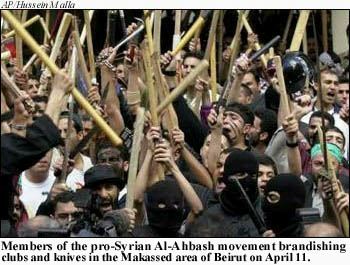

Amid this atmosphere of threats and intimidation, the opposition coalition called off the demonstration planned for April 11. Meanwhile, it was becoming clear that local surrogates of Syrian intelligence were bent on producing a display of "sectarian unrest" on April 11. On April 8, a number of masked individuals assembled outside a Sunday afternoon ceremony at UNESCO Palace commemorating the founding of Syria's ruling Ba'ath Party and handed out flyers, signed by the hitherto unheard of "Islamic Awakening Brigades," which vowed to fight anti-Syrian demonstrators with clubs and kitchen knives on April 11. "We implore the Interior Ministry and security and military agencies not to intervene, and let us pursue them to wherever they gather so that we can teach them a lesson that will bring them back to their senses," the statement added. The Association of Islamic Philanthropic Projects, more commonly known as Al-Ahbash, and the Lebanese branch of Syria's ruling Ba'ath party issued similar statements.

On April 11, Al-Ahbash militants waving knives and clubs staged demonstrations at three different locations in Beirut. The total number of Al-Ahbash members who took to the streets was fairly small, but plainclothes intelligence officers herded them together in front of television crews, stage-managing each event so as to fill the camera frames. One Lebanese newspaper described the spectacle taking place outside the movement's headquarters at the Bourj Abi Haidar Mosque as follows:

An ISF [internal security forces] officer helped the organizers block off the streets - seconds after an army patrol drove by. A man on a loudspeaker then instructed the group to return to the mosque. Another man gathered up the journalists, directing them to another location where a second "demonstration" was about to start.20The presence of many apathetic participants wearing dirty overalls indicated that more than a few of the thousands of Syrian construction workers in Beirut were brought in at the last minute. Meanwhile, hooded members of the so-called "Islamic Awakening Brigades" distributed provocative leaflets at mosques and major intersections in Beirut.

|

Nevertheless, April 11 was indeed a day of violence - not in Beirut, but in the Druze village of Bkheshtey, where the sister and niece of Druze MP Akram Chehayyeb, a senior aide to Jumblatt, were severely injured by a mail bomb. The blast occurred as his niece, Jihan Chehayyeb, opened a box placed at the doorstep to the house of the father of her fiancée, Iyad Jamaleddine, to whom the package was addressed. Sources close to the PSP believe that Jamaleddine, who currently resides in Europe and has been involved in opposition activities abroad, was the intended target.

"It is not through terrorism that we will reach dialogue," Jumblatt said somberly after the bombing. Other Druze political figures concurred that the attack was designed to enflame sectarianism. "This bomb doesn't target us alone," said Information Minister Ghazi Aridi, a member of Jumblatt's PSP, after visiting the victims at the hospital. "It targets Lebanon's stability." 21

Has Unity Prevailed?

It does not appear that Syrian intimidation is having the intended effect of silencing Lebanese Muslims. Shortly after the events of April 11, a group of Lebanese Sunnis in Europe headed by Dr. Muhammad Dergham released a statement announcing the establishment of the Sunni Muslim Lebanese League (Al-Rabita Al-Islamiyya Al-Sunniyya Al-Lubnaniyya), which staunchly condemned the Syrian occupation of Lebanon. The statement said that Syria had "confiscated" the political will of the Lebanese Sunni community and appointed leaders who are "totally submissive to the Syrian intelligence services."

"After a week in which some Lebanese seriously thought their country was on the verge of a new sectarian war, what did events on Wednesday [April 11] boil down to?" read a leading editorial in one Beirut daily newspaper. "Basically, a few Ba'ath and Ahbash heavies dressed up as bank robbers waving sticks before the cameras. So much for widespread Muslim disapproval of a possible Syrian departure."21

Notes

1 L'Orient Le Jour (Beirut), 16 March 2001.

2 "Sectarian Violence Erupts in Suweida," Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, December 2000.

3 Future Television (Beirut), 16 March 2001.

4 L'Orient Le Jour (Beirut), 16 March 2001.

5 Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), 18 March 2001.

6 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 20 March 2001.

7 Press release, The National Gathering for Salvation and Change, 1 April 2001.

8 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 9 April 2001.

9 The Daily Star (Beirut), 26 March 2001 and 27 March 2001.

10 Radio Lebanon (Beirut), 24 November 2000; Al-Sharq Al-Awsat (London), 28 November 2000.

11 The Daily Star (Beirut), 24 February 2001.

12 Al-Mustaqbal (Beirut), 8 March 2001.

13 The Daily Star (Beirut), 22 March 2001.

14 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 21 March 2001.

15 The Daily Star (Beirut), 7 April 2001.

16 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 5 April 2001.

17 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 6 April 2001.

18 The Daily Star (Beirut), 10 April 2001.

19 Al-Nahar (Beirut), 12 April 2001.

20 The Daily Star (Beirut), 12 April 2001.

21 The Daily Star (Beirut), 12 April 2001.