|

| Vol. 2 No. 7 | Table of Contents MEIB Main Page | 5 August 2000 |

|

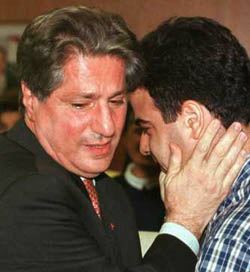

| Gemayel and son (AP/Mahmmoud Tawil) |

The last president of Lebanon's First Republic arrived home after 12 years of exile on July 30 and warmly embraced the country's Syrian-installed puppet regime. Although many Lebanese were dismayed by the sudden turnabout of this leading political opposition figure, few were surprised. Lebanon's curse has always been the tendency of even its most well-intentioned political elites to compromise their principles in the pursuit of political objectives. If the story of Gemayel's return seems eerily familiar, it is because the same play has repeated itself endlessly over the last twenty-five years, with different actors and different settings, but always the same tragic finale.

Gemayel was at times vehemently opposed to the presence of Syrian forces in Lebanon during his tenure in office from 1982 to 1988. In the early 1980's, when American assistance to Lebanon reached its high point, Gemayel firmly opposed Syria's occupation of Lebanese territory and attempts by its militia proxies to terrorize the population into submission. Although he was unable to achieve this goal, he distinguished himself with one remarkable act of courage that would have enormous symbolic and legal implications for the future: On September 1, 1983, he sent Hafez Assad an official request for the withdrawal of Syrian military forces in Lebanon,1 definitively contradicting Assad's claim that Syrian forces were legally stationed there at the request of its government (the Syrians were outraged and categorically rejected the request).

After the withdrawal of American peacekeepers in 1984, Gemayel found that his attempts to negotiate an end to the "civil" war with militia leaders such as Amal leader Nabih Berri and Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) leader Walid Jumblatt kept leading back to the Syrians, who demanded that Gemayel permanently legalize the Syrian presence. Every single "reconciliation accord" put forward by Syria's militia allies contained this provision. Gemayel searched in vain for a compromise solution, visiting Damascus repeatedly in the 1980's, but to no avail.

As his term drew to a close, the Syrians sought to isolate Gemayel politically and ensure the election of a new president that would accept Syrian hegemony over Lebanon.2 In the summer and fall of 1988, Syrian forces and the Christian Lebanese Forces (LF) militia each prevented parliament members in areas under their control to convene and elect a new president. Fifteen minutes before the expiration of his term, Gemayel appointed Gen. Michel Aoun, the commander of the Lebanese Army, as interim prime minister to head a caretaker government until parliament could freely elect the next president. Gemayel did not stay around to witness Aoun's dramatic, but failed, attempt to liberate the country by force of arms in 1989-90. Ironically, it was threats by Lebanese Forces militia, not the Syrians, that led to Gemayel's decision to leave the country.

During his twelve years in exile, Gemayel found himself overshadowed by Aoun's unrivaled popularity among the Lebanese diaspora, but remained hopeful that the U.S. government (which remained fiercely opposed to Aoun) would take a more proactive role in restoring Lebanese sovereignty. He occasionally expressed interest in returning to his homeland, but the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon, Gen. Ghazi Kanaan, is said to have opposed his return and Lebanese officials often alluded to the possibility of criminal charges being filed against the former president upon his return.

Syria's recent decision to let Gemayel return probably has a great deal to do with Aoun's continuing popularity in Lebanon, which made Gemayel an attractive counterweight that could be used to divide the opposition. Gemayel, on the other hand, grew eager to assist the political career of his son, Pierre by helping him to assert his leadership within the extended Gemayel family and the Kata'ib Party. These parochial turf battles could not be effectively waged from Paris, and so Gemayel set out to negotiate the conditions of his return.

A well-informed source told MEIB that Gemayel initiated negotiations with the Syrians through several intermediaries, including Joseph Abou-Khalil, editor of the Nida al-Watan newspaper; Mehdi al-Tajir, a Shi'ite UAE businessman close to the Syrian regime who had previously mediated between Gemayel and Damascus during the 1980's; and Gen. Ibrahim Hueiji, the head of Syrian air force intelligence, who had known Gemayel very well (too well, Gemayel's younger brother Bashir often complained) when he was commander of Syrian forces in Sin al-Fil, north Metn, in the late 1970's. These intermediaries communicated to the new Syrian regime that Gemayel was willing to observe the "red lines" imposed by Damascus on the activities of Lebanese politicians in exchange for permission to return.

Syria's ruling Ba'ath Party extended Gemayel an official invitation to visit Syria and attend a ceremony marking the end the of traditional 40-day mourning period for the late Syrian president. However, on the morning of July 19, just minutes before his flight left for Beirut, Gemayel supposedly received a call from the Lebanese ambassador in Paris, who relayed a message from the Lebanese Foreign Ministry indicating that the Syrian invitation had been a "protocol mistake." In actuality, Lebanese officials had intervened at that point with an additional requirement for Gemayel's return: that his son Pierre, who had officially declared his candidacy in the upcoming parliamentary elections the week before, not join the electoral list of Metn MP Nassib Lahoud. This was labeled in the press as a "master stroke" to divide the opposition by Interior Minister Michel Murr, Lahoud's main rival in Metn, but perhaps also reflected President Emile Lahoud's desire to curb the influence of his estranged cousin. In any case, the matter was resolved by the end of the month and Gemayel flew home to an emotional reception at his hometown of Bikfaya.

Upon his arrival in Lebanon, Gemayel proclaimed that he was "ready and willing to have brotherly and fruitful cooperation" with Syria's new president and wasted little time in meeting with top figures of the Lebanese regime.3 On August 1, he was warmly received by Lebanese President Emile Lahoud and permitted the honor of officially reviewing Lebanese military units. He then traveled to Nijmeh Square and met with Berri (who in Gemayel's absence had been elevated to speaker of parliament). Afterwards, Gemayel praised the former militia warlord as an "old friend," adding that the two had always been "on the same wavelength."4 Gemayel visited Prime Minister Salim al-Hoss the next day and afterwards told reporters that Hoss "has always acted as the country's conscience and served the interests of the country and citizens,"5 apparently forgetting that Hoss boycotted Gemayel's own cabinet meetings (following Syrian instructions) for nearly two years during a previous term as prime minister in the late 1980's and later headed a rival Syrian puppet regime in West Beirut during the civil war.

"His role as a potential opponent to the present regime, as the public has tended to envision him in recent years," wrote Beirut's Daily Star in typical understated fashion, "appears to have been put on hold for the time being."6

1 The full text of Gemayel's request, addressed directly to Assad, is provided by former Lebanese Foreign Minister Elie A. Salem in his memoirs, Violence and Diplomacy in Lebanon (London: I.B. Taurus, 1995), pp. 115-116.

2 In February 1988, Gemayel's security team found a sophisticated explosive charge on board his plane. Before they could examine it and determine its origin, however, Syrian intelligence officers at Beirut International airport seized the device and refused to relinquish it (which, ironically, had the effect of answering this very question to the satisfaction of most observers).

3 The Daily Star (Beirut) 31 July 2000.

4 The Daily Star (Beirut) 2 August 2000.

5 Al-Safir (Beirut), 3 August 2000.

6 The Daily Star (Beirut) 2 August 2000.